肝豆状核变性动物模型的研究进展

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.05.041

-

摘要: 肝豆状核变性(WD)是一种罕见的常染色体隐性遗传病,其发病机制复杂,涉及多系统多脏器及体内复杂的铜稳态调节系统,其中肝脏是铜离子最常沉积的器官,肝损伤也是WD最早和最常见的表现,因此寻找一种理想的动物模型在WD研究中非常重要。本文通过对目前国际上常用的WD动物模型进行综述,系统地归纳了不同模型的背景,肝脏、神经等系统表现以及模型应用,并对不同动物模型的特点进行了比较,为各类WD动物模型的应用提供借鉴。Abstract: Wilson's disease (WD) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder with a complex pathogenesis involving multiple systems, multiple visceral organs, and the complex copper homeostasis regulation system within the body. The liver is the most common organ for copper deposition, and liver injury is the earliest and most common manifestation of WD; therefore, it is important to find an ideal animal model for WD research. By summarizing the animal models of WD commonly used in the world, this article systematically summarizes the background, liver and nervous manifestations, and application of different models and compares the characteristics of different animal models, so as to provide a reference for the application of various animal models of WD.

-

Key words:

- Hepatolenticular Degeneration /

- Liver Diseases /

- Disease Models, Animal

-

检验项目参考区间是临床疾病诊断与健康监测的主要依据,参考区间的准确性、适用性直接影响着临床判断。2012年,我国卫生行业标准发布了血清AST、ALT、GGT、ALP等项目的参考区间,同时指出该参考区间可能受民族、地区影响而致其不适用,各实验室可自行建立参考区间[1]。目前建立参考区间的方法有直接法[2]和间接法[3],直接法需通过建立严格的排除标准而筛选符合要求的参考个体,且此法过程漫长繁琐、难以实施;而间接法只需通过数学统计,凭借快速简便、能得到与直接法相似结果的优势脱颖而出。本研究利用临床实验室信息系统(laboratory information system,LIS)已有数据,用数学统计模型建立AST、ALT、GGT、ALP间接法参考区间,并与国家行业标准比较,以期为临床疾病诊断与健康监测提供依据和参考。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

收集本院2019年10月—2020年10月LIS中体检中心健康人群数据,排除信息不全及溶血、脂血、黄疸等不合格样本后,通过比对样本号、姓名、年龄、就诊日期等信息确认为同一来源选择首次测量结果。共入组20~79岁健康人群数据29 443例,其中男性13 423例、女性16 020例。

1.2 仪器与试剂

使用日立公司的7600-210全自动生化分析仪、上海科华公司的试剂与标准品、美国伯乐公司的室内质控品。仪器每年由厂家进行一次校准,每日8点前至少对高、中、低值质控品进行测定(批号:45803,45802,45801)。

1.3 研究方法

AST的检测方法为紫外-苹果酸脱氢酶法,ALT的检测方法为紫外-乳酸脱氢酶法,GGT的检测方法为L-γ-谷氨酰-3-羧基-4-硝基苯氨法,ALP的检测方法为AMP缓冲液法。研究对象空腹8 h后于次日上午7∶ 30—9∶ 30安坐,自肘前静脉真空采血4 ml,常温送至检验科进行上述4种生化指标检测。

1.4 伦理学审查

本研究方案经由吉林大学第一医院伦理委员会批准,批号:2019-249。

1.5 统计学方法

利用SPSS 23.0、Minitab 17、LMS chartmaker Light 2.54、Excel 2016软件分析数据。柯尔莫哥洛夫-斯米诺夫检验判断数据正态性,若其呈偏态分布则使用BOC-COX法转换,此法中的待定变换参数λ由极大似然法求得,其值由所有数据决定。BOX-COX法可针对不同的λ做出不同变换。转换后的数据经P-P图检验为近似正态分布后,使用Turkey法剔除离群值。剔除时把四项指标视为一个整体,若其中任意一个指标符合剔除标准则剔除此人全部信息。Spearman相关分析判断AST、ALT、GGT、ALP与年龄的相关性。LMS法建立连续百分位数曲线。Mann-Whitney U检验比较性别差异,5岁为一年龄组,Z检验比较年龄差异。用数据均值、标准方差及样本量计算Z与Z*值,如Z>Z*则差异有统计学意义,需分组建立参考区间[2]。非参数法计算数据分布的2.5%和97.5%百分位值作为参考区间的上、下限,并用Bootstrap计算其90%置信区间。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

1.6 参考区间的验证

选取本院2020年11月体检中心20~79岁健康人群作为验证个体,对新建立的参考区间进行适用性验证[4],并参照我国行业标准:参考个体多于20例且落在参考区间内的数据≥90%,则通过验证。计算各指标参考区间上、下限值与我国行业标准及其他研究的相对偏差,并与相应参考变化值(reference change value,RCV)比较,其中RCV的计算公式为 RCV=√2×Z×√CV2a+CV2i(CVa为分析变异系数、CVi为个体内生物学变异系数,通过Westgard网站获得;Z为差异的可能性概率,95%的可能性概率取值1.96),若相对偏差>RCV则认为二者间差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 数据分布与离群值剔除

调取的AST、ALT、GGT、ALP数据均不服从正态分布,使用BOX-COX法将其转换为近似正态分布,其中四组数据的待定变换参数λ分别为-0.80、-0.78、0.25、-0.10。使用Turkey法剔除数据2225例,其中男性1213例,女性1012例。正态转换及离群值剔除前后具体数据详见表 1。

表 1 BOX-COX变换及剔除前后数据分布指标 数据类型 样本量(例) 均值 标准差 全距 中位数 P25 P75 AST (U/L) 原始数据 29 443 21.39 9.11 219.70 19.30 16.40 23.60 转换后 29 443 0.09 0.02 0.33 0.09 0.08 0.11 剔除后 27 218 20.58 6.14 40.10 19.20 16.40 23.10 ALT (U/L) 原始数据 29 443 22.69 17.08 385.90 17.80 12.60 26.70 转换后 29 443 0.11 0.05 1.70 0.11 0.08 0.14 剔除后 27 218 21.29 13.01 122.80 17.60 12.70 25.50 GGT (U/L) 原始数据 29 443 25.51 20.39 149.20 18.70 12.50 26.70 转换后 29 443 2.17 0.37 2.59 2.09 1.89 2.37 剔除后 27 218 22.91 14.51 75.80 18.20 12.50 28.90 ALP (U/L) 原始数据 29 443 60.38 17.50 313.90 58.00 48.30 69.70 转换后 29 443 0.66 0.02 0.22 0.66 0.64 0.67 剔除后 27 218 59.94 15.90 92.80 57.90 48.30 69.30 注:剔除部分为离群值。 2.2 AST、ALT、GGT、ALP水平的性别及年龄间比较

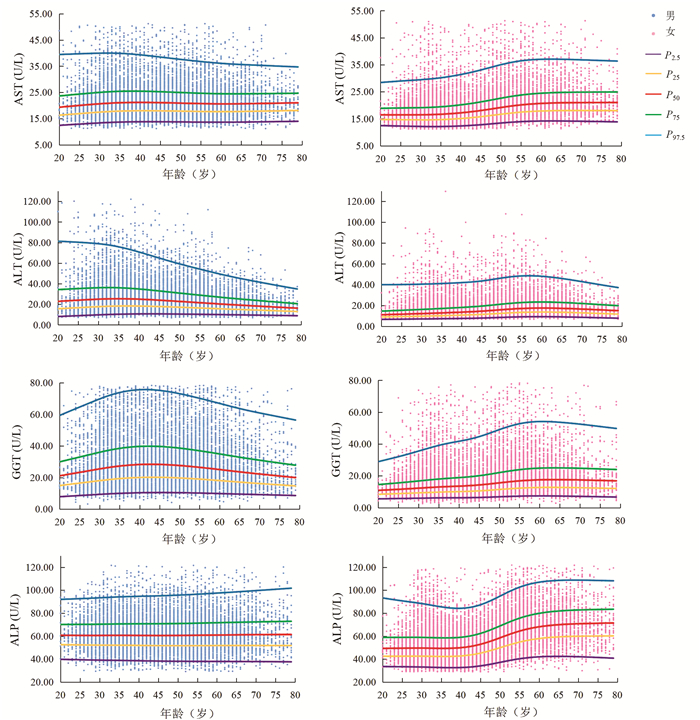

Mann-Whitney U检验结果显示,AST在20~54岁性别间差异有统计学意义(7个年龄段Z值分别为-5.68、-15.59、-30.14、-25.86、-19.22、-15.12、-4.29,P值均 < 0.05)。ALT、GGT、ALP在各年龄组不同性别间差异均有统计学意义(ALT各年龄段Z值分别为-10.27、-24.71、-39.41、-33.86、-28.14、-26.94、-15.17、-11.52、-5.90、-4.77、-3.20、-3.83;GGT各年龄段Z值分别为-12.06、-24.95、-39.70、-34.04、-31.95、-31.61、-23.33、-19.20、-13.54、-9.46、-6.29、-3.65;ALP各年龄段Z值分别为-8.32、-16.36、-22.67、-23.55、-20.42、-14.99、-4.62、-12.77、-10.20、-8.54、-5.03、-2.59,P值均 < 0.05)。Spearman相关结果显示,男性ALT(r=-0.191, P<0.001)、GGT(r=-0.041, P<0.001)与年龄呈负相关;女性AST(r=0.365, P<0.001)、ALT(r=0.310, P<0.001)、GGT(r=0.264, P<0.001)及ALP(r=0.411, P<0.001)与年龄呈正相关。分组后各亚组样本量均大于120例。男性ALT、GGT及女性AST、ALT、GGT、ALP的年龄差异均有统计学意义(Z>Z*)。AST、ALT、GGT、ALP水平连续百分位数曲线见图 1。

2.3 参考区间的建立、验证及比较

用于验证的样本剔除离群值后共10 598例,其中男性6292例、女性4306例。男性、女性共14个亚组,各组验证样本量均>20例,4项生化指标均有>90%的测定值落在本研究参考区间内。使用非参数方法计算的AST、ALT、GGT、ALP参考区间及适用性验证见表 2。为与我国行业标准保持一致,本研究结果取整数。AST、ALT、GGT和女性20~49岁ALP参考区间与我国行业标准的相对偏差均低于RCV,男性及50~79岁女性ALP参考区间与我国行业标准的相对偏差高于RCV。本研究结果与国内外研究结果比较见表 3。

表 2 AST、ALT、GGT、ALP参考区间及适用性验证指标 分组 样本量(例) P2.5 90%置信区间 P97.5 90%置信区间 验证样本量(例) 验证通过率(%) 性别 年龄(岁) 下限 上限 下限 上限 AST (U/L) 男 20~79 12 210 13.50 13.40 13.60 39.30 38.60 39.90 6292 95.12 女 20~49 10 035 12.20 12.10 12.30 32.40 31.61 33.20 2744 95.70 50~79 4973 13.90 13.70 14.00 38.60 37.60 39.60 1562 96.16 ALT (U/L) 男 20~54 8714 10.39 10.10 10.50 70.53 69.13 72.24 4544 93.90 55~79 3496 9.90 9.54 10.00 49.26 47.77 51.47 1748 94.79 女 20~49 10 035 7.40 7.30 7.40 42.60 41.20 43.81 2744 93.95 50~79 4973 9.00 8.84 9.20 49.27 48.03 50.80 1562 94.88 GGT (U/L) 男 20~64 11 195 10.50 10.39 10.80 69.90 69.11 70.50 5732 90.25 65~79 1015 10.00 9.30 10.30 64.20 59.80 66.80 560 94.29 女 20~49 10 035 6.20 6.10 6.30 44.90 43.50 46.59 2744 95.48 50~79 4973 7.40 7.20 7.60 54.23 51.90 58.00 1562 94.30 ALP (U/L) 男 20~79 12 210 37.90 37.60 38.40 95.97 95.02 97.20 6292 92.39 女 20~49 10 035 33.00 32.70 33.30 88.72 87.42 90.40 2744 93.11 50~79 4973 40.20 39.70 41.00 106.30 105.30 107.43 1562 91.87 表 3 本研究与其他研究结果比较指标 本研究(间接法) 我国行业标准(直接法) 俄罗斯(直接法) 沙特阿拉伯(直接法) 我国上海(间接法) RCV(%) 年龄(岁) 男 女 年龄(岁) 男 女 相对偏差(%) 年龄(岁) 男 女 相对偏差(%) 年龄(岁) 男 女 相对偏差(%) 年龄(岁) 男 女 相对偏差(%) AST (U/L) 20~79 14~39 20~19 15~45 13~40 (7.14, 15.38) 18~64 15~41 14~32 (7.14, 5.13) 18~65 11~28 10~24 (21.43, 28.21) 20~79 15~46 13~38 (7.14, 17.95) 38.12 20~49 12~32 (8.33, 25.00) (16.67, 0) (16.67, 25.00) (8.33, 18.75) 38.12 50~79 14~39 (7.14, 2.56) (0, 17.95) (28.57, 38.46) (7.14, 2.56) 38.12 ALT (U/L) 20~54 10~71 20~19 9~60 1~45 (10.00, 15.49) 18~64 11~51 7~31 (10.00, 28.17) 18~65 7~39 5~18 (30.00, 45.07) 20~79 8~555 5~42 (20.00, 22.54) 60.12 55~19 10~49 (10.00, 22.45) (10.00, 4.08) (30.00, 20.41) (20.00, 12.24) 60.12 20~49 7~43 (0, 4.65) (0, 27.91) (28.57, 58.14) (28.57, 7.69) 60.12 50~79 9~49 (22.22, 8.16) (22.22, 36.73) (44.44, 63.27) (44.44, 2.33) 60.12 GGT (U/L) 20~64 11~70 20~19 10~60 1~45 (9.09, 13.m) 18~64 12~69 8~32 (9.09, 0) 18~65 11~65 7~21 (0, 5.80) 20~79 16~52 8~39 (45.45, 25.71) 41.53 65~79 10~64 (0, 6.25) (20.00, 7.81) (10.00, 1.56) (60.00, 18.75) 41.53 20~49 6~45 (16.66, 0) (33.33, 28.89) (16.67, 53.33) (33.33, 13.33) 41.53 50~79 7~54 (0, 16.66) (14.29, 40.74) (0, 61.11) (14.29, 27.78) 41.53 ALP (U/L) 20~79 38~96 20~19 45~125 (18.42, 30.21) 18~64 46~121 (21.05, 26.04) 18~65 39~114 (2.63, 18.75) 19.99 20~49 33~89 20~49 35~100 (6.06, 12.36) 18~44 38~89 (15.15, 0) (18.18, 28.09) 19.99 50~79 40~106 50~19 50~135 (25.00, 27.36) 45~64 44~128 (10.00, 20.75) (2.50, 7.55) 19.99 3. 讨论

血清AST、ALT、GGT、ALP作为常规肝功能检测的四项指标对肝肾疾病的诊断及治疗至关重要。近年有研究表明,AST、ALT与癌细胞代谢密切相关,并与不同类型癌症的预后有关[5];ALT与非酒精性脂肪肝性肝炎的肝脏炎症、肝纤维化及肝脂肪变性程度显著相关[6]。也有研究[7]结果显示,GGT、ALP与肾脏预后独立相关。故建立其准确可靠的参考区间具有重要意义。

本研究中男性随年龄增加,ALT、GGT水平先上升后下降,验证了我国多中心研究[8]中男性ALT、GGT水平在40岁前随年龄升高,在40岁后保持不变或下降的结论。这种趋势的可能原因是,ALT、GGT水平与酒精有关[9],人进入中老年期,中度或重度饮酒人士数量减少。本研究中女性AST、ALT、GGT、ALP水平均随年龄增加,在45~55岁时上升明显,验证了我国多中心研究[8]中女性AST、ALT、GGT、ALP与年龄正相关、我国北京[10]ALP水平在50岁后升高的结论。女性45~55岁呈现出的特殊性可能与其生理变化有关,大多数女性在该年龄段步入更年期、绝经期,性激素波动明显。本研究中男性或女性ALT水平在60岁后均有不同程度下降,验证了美国老年人ALT水平与年龄呈负相关的研究结果[11],提示临床医生在解释患者(尤其是老年人)ALT水平时应考虑年龄因素。

通过相对偏差与RCV比较,本研究自建的男性ALP参考区间上限、女性50~79岁ALP参考区间上、下限与我国行业标准间差异有统计学意义(相对偏差>RCV)。男性GGT参考区间下限与我国上海的研究[12]、女性AST、GGT、ALP参考区间上限与沙特阿拉伯的研究[13]、男性ALP参考区间上、下限及50~79岁女性ALP参考区间上限与俄罗斯的研究[14]差异有统计学意义(相对偏差>RCV)。造成差异的原因可能是:(1)这4项生化指标与BMI有关[14-15],或与人群、种族、遗传、地域、生活习惯、饮食结构等有关;(2)样本量不足,纳入研究的数据不足以代替整个人群;(3)不同实验室建立参考区间的检测方法、试剂、仪器等差异;(4)可能存在异常数据,虽经过离群值剔除但不能确保纳入研究的个体为完全健康没有疾病。自建的ALP参考区间与我国行业标准间的差异可通过增加样本量来改善。另外本研究建立的参考区间通过适用性验证,表明该参考区间适用于本地区人群,证实间接法建立参考区间的可行性。此前本实验室已使用直接法建立了长春地区儿童血清AST、ALT、GGT、ALP参考区间[16-17]。直接法虽是建立参考区间的标准方法,但其过程漫长繁琐,如需面对特殊群体(新生儿、孕妇、老人等)会使数据更加难以收集。若实验室直接引用试剂厂商提供的参考区间,难免存在种族、环境等差异。而间接法利用已有数据既可获得特殊群体足够多的数据量,又无需额外投入,是一种很好的选择,适合不同实验室根据本地区人群、检测系统等实际情况建立参考区间。本研究以LIS数据为基础,运用数学统计模型建立参考区间,虽可能纳入异常数据,但通过适宜数据转换、离群值剔除后计算参考区间可有效弥补这一缺陷[8]。间接法作为一种回顾性研究,其实施过程无法达到与直接法一致的严谨程度,各界对其存在一定争议,故应定期验证间接法建立的参考区间以确保其可靠性。本研究根据数据分布及样本量选择了BOX-COX法、Turkey法与非参数法,目前尚不能评价本研究所用方法的优劣。尽管如此,间接法仍然凭借着简单快速的优势在未来有很好的应用前景。

血清酶与性别、年龄等因素关系密切,故应根据性别及年龄建立参考区间。本研究使用间接法建立了成人血清AST、ALT、GGT、ALP的性别及年龄特异性参考区间。该参考区间与我国行业标准较为一致,证实间接法建立参考区间的可信度和可靠性。本研究为血清酶类参考区间研究提供了基础数据,有益于肝病及其他相关疾病的预防及鉴别诊断。

-

表 1 常见WD动物模型特点

Table 1. Characteristics of common WD animal models

模型种类 肝损伤

症状神经系统症状

(无/轻微/明显)K-F环

(有/无)母乳中是否含

有铜(有/无)应用特点 TX小鼠 有 无 无 无 肝损伤出现较早且表现突出,应用较广泛 TX-J小鼠 有 轻微 无 无 铜沉积出现较早,适合进行铜代谢等方面研究,应用较广 ATP7B-/-小鼠 有 无 无 无 肝铜沉积较早且含量较高,适用于疗效评估,但价格昂贵,目前应用尚不广泛 LEC大鼠 有 轻微 无 有 肝病进展迅速,适合用于进行干预研究,但大鼠病死率较高 -

[1] SUN ZR, YANG WM. Neurology[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2016.孙忠人, 杨文明. 神经病学[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2016. [2] CZŁONKOWSKA A, LITWIN T, DUSEK P, et al. Wilson disease[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2018, 4(1): 21. DOI: 10.1038/s41572-018-0018-3. [3] XU CC, DONG JJ, CHENG N, et al. Effects of Gantou decoction serum on ATP7b protein subcellular localization and functional expression in Wilson disease model tx mice[J]. Chin J Tradit Chin Med Pharm, 2017, 32(1): 250-253. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BXYY201701069.htm徐陈陈, 董健健, 程楠, 等. 中药肝豆汤含药血清对Wilson病模型TX小鼠肝细胞内ATP7b蛋白亚细胞定位和功能表达的影响[J]. 中华中医药杂志, 2017, 32(1): 250-253. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-BXYY201701069.htm [4] ZHAO W, CHENG N, HAN YZ. Research progress of Wilson's disease animal model[J]. Anhui Med J, 2014, 35(11): 1611-1614. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0399.2014.11.046.赵雯, 程楠, 韩咏竹. Wilson病的动物模型研究进展[J]. 安徽医学, 2014, 35(11): 1611-1614. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-0399.2014.11.046. [5] REED E, LUTSENKO S, BANDMANN O. Animal models of Wilson disease[J]. J Neurochem, 2018, 146(4): 356-373. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.14323. [6] XIA M, SUN YH, WANG M, et al. Research progress of common animal models of primary hepatocellularcarcinoma[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2021, 37(8): 1938-1942. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2021.08.042.夏猛, 孙玉浩, 王萌, 等. 原发性肝癌常见动物模型的研究进展[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2021, 37(8): 1938-1942. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2021.08.042. [7] RAUCH H. Toxic milk, a new mutation affecting cooper metabolism in the mouse[J]. J Hered, 1983, 74(3): 141-144. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109751. [8] CHEN X, WANG CH, FENG YQ, et al. Experimental study on copper metabolism and liver damage in TX mice[J]. Chin J Hepatol, 2009, 17(9): 688-690. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2009.09.012.陈曦, 王楚怀, 丰岩清, 等. TX小鼠铜代谢和肝损害的实验研究[J]. 中华肝脏病杂志, 2009, 17(9): 688-690. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2009.09.012. [9] ZISCHKA H, LICHTMANNEGGER J. Pathological mitochondrial copper overload in livers of Wilson's disease patients and related animal models[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2014, 1315: 6-15. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.12347. [10] HOWELL JM, MERCER JF. The pathology and trace element status of the toxic milk mutant mouse[J]. J Comp Pathol, 1994, 110(1): 37-47. DOI: 10.1016/s0021-9975(08)80268-x. [11] ZHOU XX, LI XH, CHEN DB, et al. Injury factors and pathological features of toxic milk mice during different disease stages[J]. Brain Behav, 2019, 9(12): e01459. DOI: 10.1002/brb3.1459. [12] MEDICI V, HUSTER D. Animal models of Wilson disease[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2017, 142: 57-70. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63625-6.00006-9. [13] JIN S, FANG X, BAO YC, et al. Analysis on the characteristics of wilson's disease with renal damage as the main manifestation[J]. Clin J Tradit Chin Med, 2010, 22(11): 1005-1007. DOI: 10.16448/j.cjtcm.2010.11.032.金珊, 方向, 鲍远程, 等. 以肾脏损害为主要发病表现的Wilson病特点分析[J]. 中医药临床杂志, 2010, 22(11): 1005-1007. DOI: 10.16448/j.cjtcm.2010.11.032. [14] ZHANG YH, LI M, QIN J, et al. Extra-nervous manifestations of hepatolenticular degeneration in children[J]. Clin J Appli Pediatr, 1999, 14(5): 277-278. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-515X.1999.05.024.张月华, 李明, 秦炯, 等. 儿童肝豆状核变性的神经系统外表现[J]. 实用儿科临床杂志, 1999, 14(5): 277-278. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-515X.1999.05.024. [15] WU HM, CHEN DQ, ZHENG ZD. Hepatolenticular degeneration with renal damage as the first episode (report of 18 cases)[J]. Pediatr Emerg Med, 2001, 8(3): 175-191. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4912.2001.03.031.吴红梅, 陈大庆, 郑祖德. 以肾脏损害首发的肝豆状核变性(附18例报告)[J]. 小儿急救医学, 2001, 8(3): 175-191. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4912.2001.03.031. [16] CHEN DB, FENG L, LIN XP, et al. Penicillamine increases free copper and enhances oxidative stress in the brain of toxic milk mice[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(5): e37709. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037709. [17] TANG LL, LIU DQ, LI R, et al. Protective effect and mechanism of Gandoufumu decoction on liver fibrosis in TX mice[J]. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med, 2018, 38(12): 1461-1466. DOI: 10.7661/j.cjim.20181023.312.唐露露, 刘丹青, 李睿, 等. 肝豆扶木汤对TX小鼠肝纤维化的保护作用及机制研究[J]. 中国中西医结合杂志, 2018, 38(12): 1461-1466. DOI: 10.7661/j.cjim.20181023.312. [18] ZHANG J, TANG LL, LI LY, et al. Gandouling tablets inhibit excessive mitophagy in toxic milk (TX) model mouse of Wilson disease via Pink1/Parkin pathway[J]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2020, 2020: 3183714. DOI: 10.1155/2020/3183714. [19] BUCK NE, CHEAH DM, ELWOOD NJ, et al. Correction of copper metabolism is not sustained long term in Wilson's disease mice post bone marrow transplantation[J]. Hepatol Int, 2008, 2(1): 72-79. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-007-9039-9. [20] CORONADO V, NANJI M, COX DW. The Jackson toxic milk mouse as a model for copper loading[J]. Mamm Genome, 2001, 12(10): 793-795. DOI: 10.1007/s00335-001-3021-y. [21] JOŃCZY A, LIPIŃSKI P, OGÓREK M, et al. Functional iron deficiency in toxic milk mutant mice (TX-J) despite high hepatic ferroportin: A critical role of decreased GPI-ceruloplasmin expression in liver macrophages[J]. Metallomics, 2019, 11(6): 1079-1092. DOI: 10.1039/c9mt00035f. [22] TERWEL D, LÖSCHMANN YN, SCHMIDT HH, et al. Neuroinflammatory and behavioural changes in the Atp7B mutant mouse model of Wilson's disease[J]. J Neurochem, 2011, 118(1): 105-112. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07278.x. [23] PRZYBYŁKOWSKI A, GROMADZKA G, WAWER A, et al. Neurochemical and behavioral characteristics of toxic milk mice: an animal model of Wilson's disease[J]. Neurochem Res, 2013, 38(10): 2037-2045. DOI: 10.1007/s11064-013-1111-3. [24] MORDAUNT CE, SHIBATA NM, KIEFFER DA, et al. Epigenetic changes of the thioredoxin system in the TX-J mouse model and in patients with Wilson disease[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2018, 27(22): 3854-3869. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddy262. [25] BOARU SG, MERLE U, UERLINGS R, et al. Simultaneous monitoring of cerebral metal accumulation in an experimental model of Wilson's disease by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry[J]. BMC Neurosci, 2014, 15: 98. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-98. [26] ROYBAL JL, ENDO M, RADU A, et al. Early gestational gene transfer with targeted ATP7B expression in the liver improves phenotype in a murine model of Wilson's disease[J]. Gene Ther, 2012, 19(11): 1085-1094. DOI: 10.1038/gt.2011.186. [27] KLEIN D, LICHTANNEGGER J, FINCKH M, et al. Gene expression in the liver of Long-Evanscinnamon rats during the development of hepatitis[J]. Arch Toxicol, 2003, 77(10): 568-575. DOI: 10.1007/s00204-003-0493-4. [28] SAMUELE A, MANGIAGALLI A, ARMENTERO MT, et al. Oxidative stress and pro-apoptotic conditions in a rodent model of Wilson's disease[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2005, 1741(3): 325-330. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.06.004. [29] STERNLIEB I, QUINTANA N, VOLENBERG I, et al. An array of mitochondrial alterations in the hepatocytes of Long-Evans Cinnamon rats[J]. Hepatology, 1995, 22(6): 1782-1787. [30] LEE BH, KIM JM, HEO SH, et al. Proteomic analysis of the hepatic tissue of Long-Evans Cinnamon (LEC) rats according to the natural course of Wilson disease[J]. Proteomics, 2011, 11(18): 3698-3705. DOI: 10.1002/pmic.201100122. [31] ZISCHKA H, LICHTMANNEGGER J, SCHMITT S, et al. Liver mitochondrial membrane crosslinking and destruction in a rat model of Wilson disease[J]. J Clin Invest, 2011, 121(4): 1508-1518. DOI: 10.1172/JCI45401. [32] LEVY E, BRUNET S, ALVAREZ F, et al. Abnormal hepatobiliary and circulating lipid metabolism in the Long-Evans Cinnamon rat model of Wilson's disease[J]. Life Sci, 2007, 80(16): 1472-1483. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.017. [33] HAYASHI M, FUSE S, ENDOH D, et al. Accumulation of copper induces DNA strand breaks in brain cells of Long-Evans Cinnamon (LEC) rats, an animal model for human Wilson Disease[J]. Exp Anim, 2006, 55(5): 419-426. DOI: 10.1538/expanim.55.419. [34] TOGASHI Y, LI Y, KANG JH, et al. D-penicillamine prevents the development of hepatitis in Long-Evans Cinnamon rats[J]. Hepatology, 1992, 15(1): 82-87. DOI: 10.1002/hep.1840150116. [35] KLEIN D, ARORA U, LICHTMANNEGGER J, et al. Tetrathiomolybdate in the treatment of acute hepatitis in an animal model for Wilson disease[J]. J Hepatol, 2004, 40(3): 409-416. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.034. [36] JABER FL, SHARMA Y, GUPTA S. Demonstrating potential of cell therapy for Wilson's disease with the long-evans cinnamon rat model[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2017, 1506: 161-178. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6506-9_11. [37] CHEN S, SHAO C, DONG T, et al. Transplantation of ATP7B-transduced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells decreases copper overload in rats[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(11): e111425. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111425. [38] AHMED S, DENG J, BORJIGIN J. A new strain of rat for functional analysis of PINA[J]. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 2005, 137(1-2): 63-69. DOI: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.02.025. [39] ZISCHKA H, LICHTMANNEGGER J, SCHMITT S, et al. Liver mitochondrial membrane crosslinking and destruction in a rat model of Wilson disease[J]. J Clin Invest, 2011, 121(4): 1508-1518. DOI: 10.1172/JCI45401. [40] LICHTMANNEGGER J, LEITZINGER C, WIMMER R, et al. Methanobactin reverses acute liver failure in a rat model of Wilson disease[J]. J Clin Invest, 2016, 126(7): 2721-2735. DOI: 10.1172/JCI85226. [41] FIETEN H, PENNING LC, LEEGWATER PA, et al. New canine models of copper toxicosis: diagnosis, treatment, and genetics[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2014, 1314: 42-48. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.12442. [42] HAYWOOD S, VAILLANT C. Overexpression of copper transporter CTR1 in the brain barrier of North Ronaldsay sheep: Implications for the study of neurodegenerative disease[J]. J Comp Pathol, 2014, 150(2-3): 216-224. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2013.09.002. [43] FIETEN H, GILL Y, MARTIN AJ, et al. The Menkes and Wilson disease genes counteract in copper toxicosis in Labrador retrievers: A new canine model for copper-metabolism disorders[J]. Dis Model Mech, 2016, 9(1): 25-38. DOI: 10.1242/dmm.020263. [44] HAYWOOD S, MVLLER T, MACKENZIE AM, et al. Copper-induced hepatotoxicosis with hepatic stellate cell activation and severe fibrosis in North Ronaldsay lambs: A model for non- Wilsonian hepatic copper toxicosis of infants[J]. J Comp Pathol, 2004, 130(4): 266-277. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2003.11.005. [45] BATALLER R, BRENNER DA. Hepatic stellate cells as a target for the treatment of liver fibrosis[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2001, 21(3): 437-451. DOI: 10.1055/s-2001-17558. 期刊类型引用(3)

1. 何冰,王艺婷,李雪文,许建成. 长春市不同年龄段健康成人血清心肌酶谱水平观察. 检验医学与临床. 2024(02): 151-155 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 孔焱,李晓慧,王辉,李岩,孙悦,苗强. 间接法建立新疆克拉玛依地区常规肝功能和血脂生化项目参考区间. 国际检验医学杂志. 2024(07): 858-861+866 .  百度学术

百度学术3. 张春娇,黄蓉,蔡婷婷,顾进. 基于间接法建立肾功能检验项目的生物参考区间. 湖南师范大学学报(医学版). 2024(01): 43-47 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(1)

-

本文二维码

本文二维码

计量

- 文章访问数: 1132

- HTML全文浏览量: 205

- PDF下载量: 114

- 被引次数: 4

PDF下载 ( 1905 KB)

PDF下载 ( 1905 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:  百度学术

百度学术