甘油三酯与高密度脂蛋白胆固醇比值(TG/HDL-C)对原发性肝癌发病的影响

DOI: 10.12449/JCH240418

Influence of triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio on the onset of primary liver cancer

-

摘要:

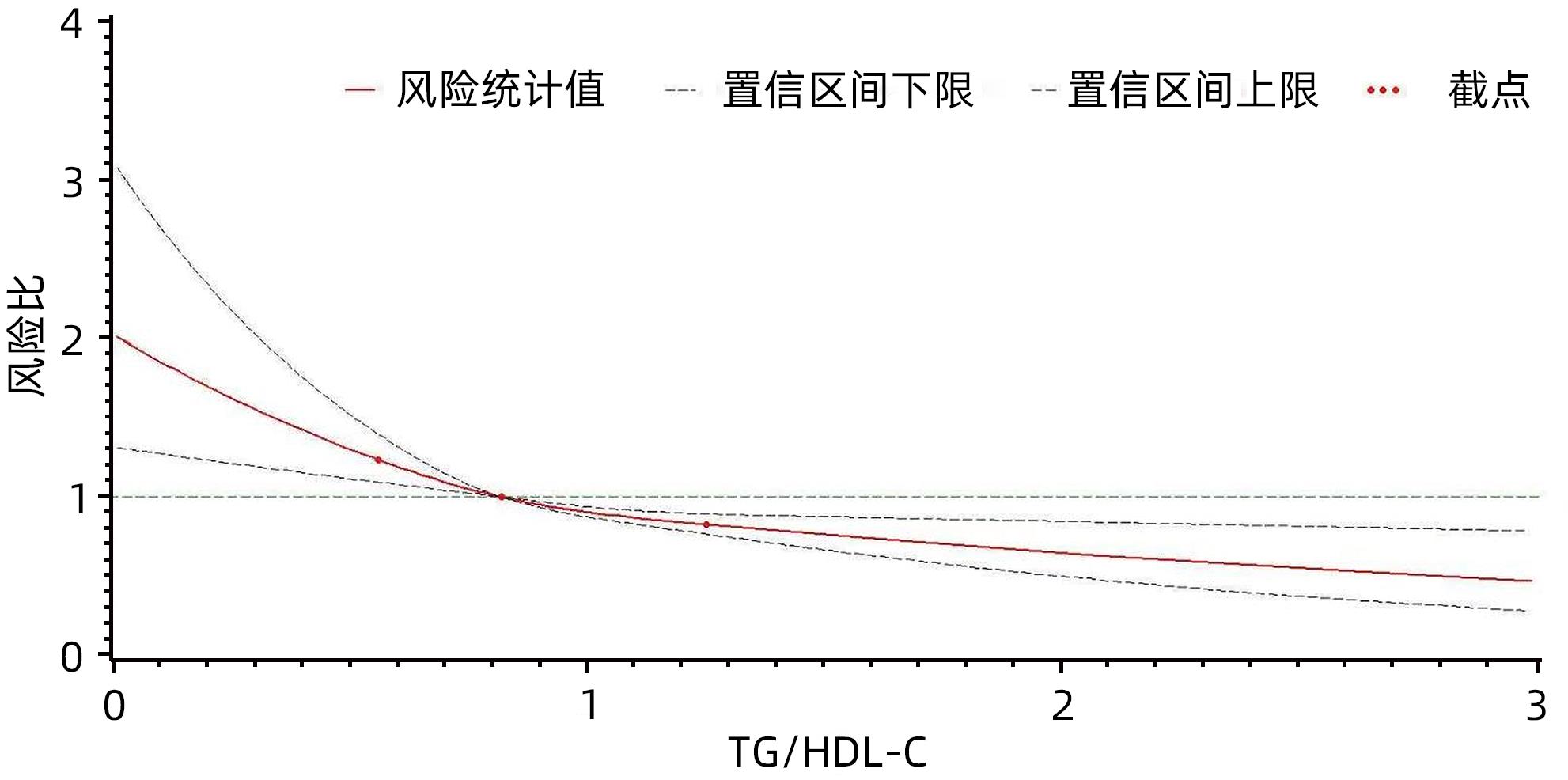

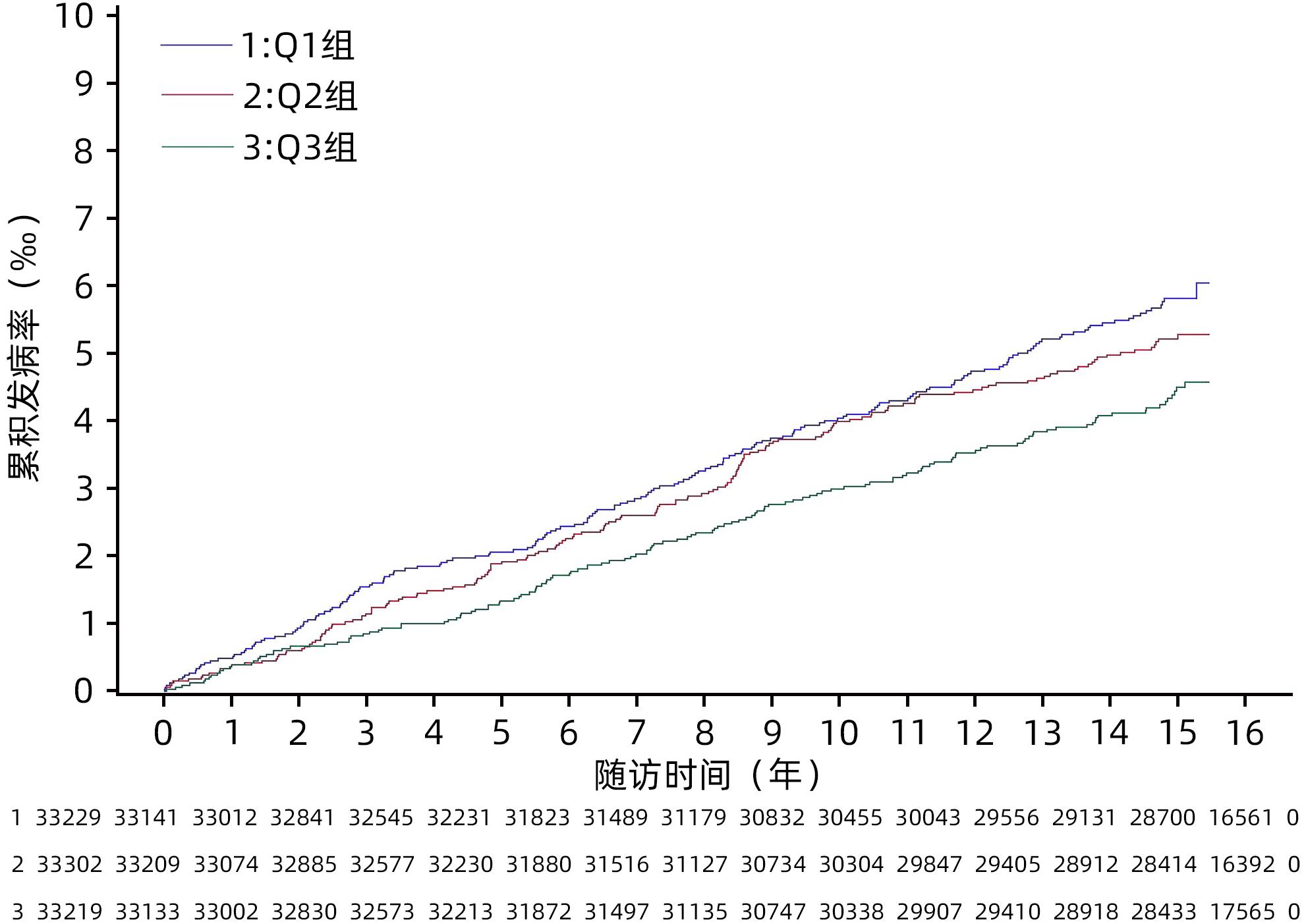

目的 探究甘油三酯与高密度脂蛋白胆固醇比值(TG/HDL-C)对原发性肝癌发病的影响。 方法 采用前瞻性队列研究的方式,收集2006年7月—2007年12月参加开滦集团健康体检的99 750例在职及离退休职工的体检资料,并对其原发性肝癌的发病情况进行随访,随访截止时间为2021年12月31日。根据TG/HDL-C三分位水平将受试者分成3组,分别为Q1组(TC/HDL-C<0.66,n=33 229)、Q2组(0.66≤TC/HDL-C<1.14,n=33 302)、Q3组(TC/HDL-C≥1.14,n=33 219)。计算各组原发性肝癌的发病密度。符合正态分布的计量资料多组间比较采用单因素方差分析;符合偏态分布的计量资料多组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis H检验。计数资料组间比较采用χ2检验。采用Kaplan⁃Meier法计算各组原发性肝癌的累积发病率,以Log-rank检验比较各组间累积发病率的差异。采用Cox比例风险模型分析不同TG/HDL-C水平分组对原发性肝癌发病的影响。 结果 3组受试者年龄、男性比例、腰围、BMI、空腹血糖、收缩压、舒张压、TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C、ALT、超敏C-反应蛋白、慢性肝病、高血压病、糖尿病、恶性肿瘤家族史、饮酒、吸烟、体育锻炼、受教育程度组间对比差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)。在平均(14.06±2.71)年的随访过程中,新发肝癌共计484例,其中男446例,女38例。Q1组、Q2组、Q3组原发性肝癌的发病密度分别是0.39/千人年、0.35/千人年、0.30/千人年。3组受试者的原发性肝癌累积发病率分别是6.03‰、5.28‰和4.49‰,经Log-rank检验,差异有统计学意义(χ2=6.06,P=0.048)。校正了考虑到的混杂因素后,Cox比例风险模型结果显示,以Q3组为对照,Q1、Q2组的风险比及95%可信区间分别为2.04(1.61~2.58)、1.53(1.21~1.92)(P for trend<0.05)。 结论 TG/HDL-C水平降低与原发性肝癌发病风险升高有关,特别是在慢性肝病的人群中这种关联更加明显。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the influence of triglyceride (TG)/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) ratio on the onset of primary liver cancer. Methods A prospective cohort study was conducted. Physical examination data were collected from 99 750 cases of on-the-job and retired employees of Kailuan Group who participated health examination from July 2006 to December 2007, and they were followed up till December 31, 2021 to observe the onset of primary liver cancer. A one-way analysis of variance was used for comparison of normally distributed continuous data between multiple groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for comparison of continuous data with skewed distribution between multiple groups; the chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between groups. According to the tertiles of TG/HDL-C ratio, the subjects were divided into Q1, Q2, and Q3 groups, and the incidence density of primary liver cancer was calculated for each group. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the cumulative incidence rate of primary liver cancer in each group, and the log-rank test was used to compare the difference in cumulative incidence rate between groups. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze the influence of TG/HDL-C ratio on the onset of primary liver cancer. Results There were significant differences between the three groups in age, proportion of male subjects, waist circumference, body mass index, fasting blood glucose, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, alanine aminotransferase, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, chronic liver diseases, hypertension, diabetes, the family history of malignant tumor, drinking, smoking, physical exercise, and educational level (P<0.05). During the mean follow-up time of 14.06±2.71 years, there were 484 cases of new-onset liver cancer, among whom there were 446 male subjects and 38 female subjects. The incidence density of primary liver cancer was 0.39/1 000 person-years in the Q1 group, 0.35/1 000 person-years in the Q2 group, and 0.30/1 000 person-years in the Q3 group, and the cumulative incidence rates of primary liver cancer in the three groups were 6.03‰, 5.28‰, and 4.49‰, respectively, with a significant difference between the three groups based on the long-rank test (χ2=6.06, P=0.048). After adjustment for the confounding factors considered, the Cox proportional hazards model showed that compared with the Q3 group, the Q1 group had a hazard ratio of 2.04 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.61 — 2.58, Pfor trend<0.05), and the Q2 group had a hazard ratio of 1.53 (95%CI: 1.21 — 1.92, Pfor trend<0.05). Conclusion The reduction in TG/HDL-C ratio is associated with an increase in the rask of primary liver cancer, especially in people with chronic liver diseases. -

Key words:

- Liver Neoplasms /

- Triglycerides /

- Cholesterol, HDL /

- Cohort Studies

-

表 1 观察对象一般资料比较

Table 1. Comparison of general information of observation objects

项目 Q1组(n=33 229) Q2组(n=33 302) Q3组(n=33 219) 统计值 P值 年龄(岁) 51.78±13.30 52.04±12.70 51.82±11.94 F=4.14 0.016 男性[例(%)] 25 170(75.75) 26 566(79.77) 27 963(84.18) χ2=735.65 <0.001 腰围(cm) 83.59±9.61 87.11±9.31 90.36±9.06 F=4 369.44 <0.001 BMI(kg/m2) 23.69±3.23 25.13±3.31 26.29±3.29 F=5 282.76 <0.001 空腹血糖(mmol/L) 5.22±1.30 5.44±1.51 5.74±1.89 F=913.58 <0.001 收缩压(mmHg) 127.50±20.60 131.37±20.73 134.25±20.65 F=892.92 <0.001 舒张压(mmHg) 81.06±11.16 83.66±11.49 85.71±11.66 F=1 377.26 <0.001 TG(mmol/L) 0.78(0.62~0.96) 1.27(1.08~1.50) 2.37(1.84~3.39) χ2=73 162.50 <0.001 TC(mmol/L) 4.86±0.94 5.01±0.99 4.96±1.31 F=161.26 <0.001 HDL-C(mmol/L) 1.74±0.43 1.52±0.34 1.38±0.35 F=7 842.03 <0.001 LDL-C(mmol/L) 2.25±0.88 2.42±0.84 2.36±0.90 F=323.32 <0.001 ALT(U/L) 16.00(11.80~22.00) 18.00(13.00~24.00) 20.00(14.00~28.00) χ2=2 939.34 <0.001 超敏C-反应蛋白 (mg/L)0.69(0.24~2.10) 0.83(0.30~2.34) 1.03(0.40~2.74) χ2=1 077.23 <0.001 慢性肝病[例(%)] 6 139(18.47) 10 732(32.23) 16 968(51.08) χ2=7 942.41 <0.001 饮酒[例(%)] 5 956(17.92) 5 264(15.81) 6 209(18.69) χ2=102.98 <0.001 吸烟[例(%)] 9 466(28.49) 9 466(28.42) 11 057(33.29) χ2=245.79 <0.001 体育锻炼[例(%)] 5 130(15.44) 4 939(14.83) 5 176(15.58) χ2=8.16 0.017 高血压病[例(%)] 11 726(35.29) 14 964(44.93) 17 130(51.57) χ2=1 807.60 <0.001 糖尿病[例(%)] 1 778(5.35) 2 822(8.47) 4 418(13.30) χ2=1 259.92 <0.001 恶性肿瘤家族史[例(%)] 1 273(3.83) 1 104(3.32) 1 283(3.86) χ2=17.78 <0.001 受教育程度[例(%)] χ2=112.91 <0.001 低等教育程度 26 073(78.46) 27 012(81.11) 26 394(79.45) 中等教育程度 4 398(13.24) 4 153(12.47) 4 478(13.48) 高等教育程度 2 758(8.30) 2 137(6.42) 2 347(7.07) 表 2 TG/HDL-C水平影响受试者原发性肝癌的Cox比例风险模型分析

Table 2. Cox proportional hazards model analysis of the effect of TG/HDL-C level on primary liver cancer

组别 发病例数/观察人数 随访时间 (人年) 发病密度 (/千人年) 模型一 模型二 模型三 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 Q1组 182/33 329 467 833.04 0.39 1.36(1.09~1.70) 0.007 1.59(1.26~2.00) <0.001 2.04(1.61~2.58) <0.001 Q2组 164/33 302 467 061.65 0.35 1.21(0.96~1.51) 0.107 1.33(1.06~1.68) 0.015 1.53(1.21~1.92) <0.001 Q3组 138/33 219 467 434.06 0.30 Ref Ref Ref P for trend 0.007 <0.001 <0.001 注:模型一校正性别和年龄;模型二在模型一的基础上进一步校正腰围、饮酒、吸烟、体育锻炼、受教育程度、高血压病、糖尿病、超敏C-反应蛋白、恶性肿瘤家族史、ALT;模型三在模型二的基础上进一步校正慢性肝病。 表 3 不同性别人群TG/HDL-C水平影响受试者原发性肝癌的Cox比例风险模型分析

Table 3. Cox proportional hazard model analysis of the effect of TG/HDL-C level on primary liver cancer in different genders

组别 男性 女性 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 Q1组 171/25 170 0.49 2.13(1.67~2.73) <0.001 11/8 059 0.09 1.22(0.50~2.95) 0.659 Q2组 149/26 566 0.40 1.55(1.22~1.97) <0.001 15/6 736 0.15 1.37(0.63~2.96) 0.424 Q3组 126/27 963 0.32 Ref 12/5 256 0.16 Ref P for trend <0.001 0.627 注:该分层分析校正的混杂因素除性别外同模型三:年龄、腰围、饮酒、吸烟、体育锻炼、受教育程度、高血压病、糖尿病、超敏C-反应蛋白、恶性肿瘤家族史、ALT和慢性肝病。 表 4 有无慢性肝病人群TG/HDL-C水平影响受试者原发性肝癌的Cox比例风险模型分析

Table 4. Cox proportional hazard model analysis of the effect of TG/HDL-C level on primary liver cancer in people with or without chronic liver disease

组别 有慢性肝病 无慢性肝病 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 Q1组 114/6 139 1.34 3.04(2.28~4.05) <0.001 68/27 090 0.18 0.97(0.66~1.41) 0.856 Q2组 96/10 732 0.64 1.66(1.24~2.22) <0.001 68/22 570 0.21 1.09(0.75~1.58) 0.652 Q3组 89/16 968 0.37 Ref 49/16 251 0.21 1.00 P for trend <0.001 0.811 注:该分层分析的校正同模型二:性别、年龄、腰围、饮酒、吸烟、体育锻炼、受教育程度、高血压病、糖尿病、超敏C-反应蛋白、恶性肿瘤家族史、ALT。 表 5 敏感性分析

Table 5. Sensitivity analysis

组别 敏感性分析一 敏感性分析二 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 发病例数/观察人数 发病密度 (/千人年) HR(95%CI) P值 Q1组 151/33 198 0.32 2.02(1.56~2.61) <0.001 180/33 039 0.38 2.06(1.62~2.62) <0.001 Q2组 144/33 282 0.31 1.60(1.25~2.05) <0.001 163/33 034 0.35 1.56(1.24~1.97) <0.001 Q3组 116/33 197 0.25 Ref 133/32 738 0.29 Ref 注:敏感性分析一,排除随访时间<2年的原发性肝癌73例,校正的混杂因素同模型三;敏感性分析二,排除基线资料或随访期间服用降脂药的观测939例,其中包括原发性肝癌8例,校正的混杂因素同模型三。 -

[1] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71( 3): 209- 249. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21660. [2] FORNER A, REIG M, BRUIX J. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391( 10127): 1301- 1314. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2 [3] MCGLYNN KA, PETRICK JL, EL-SERAG HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2021, 73( Suppl 1): 4- 13. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31288. [4] HUANG DQ, EL-SERAG HB, LOOMBA R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 18( 4): 223- 238. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [5] HANAHAN D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions[J]. Cancer Discov, 2022, 12( 1): 31- 46. DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. [6] BOROUGHS LK, DEBERARDINIS RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2015, 17( 4): 351- 359. DOI: 10.1038/ncb3124. [7] GANJALI S, BANACH M, PIRRO M, et al. HDL and cancer-causality still needs to be confirmed? Update 2020[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2021, 73: 169- 177. DOI: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.10.007. [8] GIANNINI C, SANTORO N, CAPRIO S, et al. The triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio: Association with insulin resistance in obese youths of different ethnic backgrounds[J]. Diabetes Care, 2011, 34( 8): 1869- 1874. DOI: 10.2337/dc10-2234. [9] GASEVIC D, FROHLICH J, JOHN MANCINI GB, et al. The association between triglyceride to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and insulin resistance in a multiethnic primary prevention cohort[J]. Metabolism, 2012, 61( 4): 583- 589. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.09.009. [10] TURAK O, AFŞAR B, OZCAN F, et al. The role of plasma triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio to predict new cardiovascular events in essential hypertensive patients[J]. J Clin Hypertens(Greenwich), 2016, 18( 8): 772- 777. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12758. [11] MILLER M, STONE NJ, BALLANTYNE C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2011, 123( 20): 2292- 2333. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [12] HE S, WANG S, CHEN XP, et al. Higher ratio of triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol may predispose to diabetes mellitus: 15-year prospective study in a general population[J]. Metabolism, 2012, 61( 1): 30- 36. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.05.007. [13] FAN NG, PENG L, XIA ZH, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as a surrogate for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2019, 18( 1): 39. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-019-0986-7. [14] WU SL, HUANG ZR, YANG XC, et al. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4-year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2012, 5( 4): 487- 493. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963694. [15] CHEW NWS, NG CH, TAN DJH, et al. The global burden of metabolic disease: Data from 2000 to 2019[J]. Cell Metab, 2023, 35( 3): 414- 428. e 3. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.003. [16] LI J, ZOU BY, YEO YH, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 4( 5): 389- 398. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30039-1. [17] NDERITU P, BOSCO C, GARMO H, et al. The association between individual metabolic syndrome components, primary liver cancer and cirrhosis: A study in the Swedish AMORIS cohort[J]. Int J Cancer, 2017, 141( 6): 1148- 1160. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.30818. [18] WELZEL TM, GRAUBARD BI, ZEUZEM S, et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: A study in the SEER-Medicare database[J]. Hepatology, 2011, 54( 2): 463- 471. DOI: 10.1002/hep.24397. [19] XIA B, PENG JJ, ENRICO DT, et al. Metabolic syndrome and its component traits present gender-specific association with liver cancer risk: A prospective cohort study[J]. BMC Cancer, 2021, 21( 1): 1084. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-021-08760-1. [20] CHO Y, CHO EJ, YOO JJ, et al. Association between lipid profiles and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: A nationwide population-based study[J]. Cancers(Basel), 2021, 13( 7): 1599. DOI: 10.3390/cancers13071599. [21] BORENA W, STROHMAIER S, LUKANOVA A, et al. Metabolic risk factors and primary liver cancer in a prospective study of 578, 700 adults[J]. Int J Cancer, 2012, 131( 1): 193- 200. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.26338. [22] KASMARI AJ, WELCH A, LIU GD, et al. Independent of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma risk is increased with diabetes and metabolic syndrome[J]. Am J Med, 2017, 130( 6): 746. e1- 746. e 7. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.12.029. [23] SHEILA SHERLOCK D. Alcoholic liver disease[J]. Lancet, 1995, 345( 8944): 227- 229. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90226-0. [24] HALSTED CH. Nutrition and alcoholic liver disease[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2004, 24( 3): 289- 304. DOI: 10.1055/s-2004-832941. [25] CHROSTEK L, SUPRONOWICZ L, PANASIUK A, et al.[J]. Clin Exp Med, 2014, 14( 4): 417- 421. DOI: 10.1007/s10238-013-0262-5. [26] GHADIR MR, RIAHIN AA, HAVASPOUR A, et al. The relationship between lipid profile and severity of liver damage in cirrhotic patients[J]. Hepat Mon, 2010, 10( 4): 285- 288. [27] PEREZ-MATOS MC, SANDHU B, BONDER A, et al. Lipoprotein metabolism in liver diseases[J]. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2019, 30( 1): 30- 36. DOI: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000569. [28] LONG J, ZHANG CJ, ZHU N, et al. Lipid metabolism and carcinogenesis, cancer development[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2018, 8( 5): 778- 791. [29] MICHIEL DF, OPPENHEIM JJ. Cytokines as positive and negative regulators of tumor promotion and progression[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 1992, 3( 1): 3- 15. [30] MOTTA M, GIUGNO I, RUELLO P, et al. Lipoprotein(a) behaviour in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Minerva Med, 2001, 92( 5): 301- 305. -

PDF下载 ( 802 KB)

PDF下载 ( 802 KB)

下载:

下载: