尿肝型脂肪酸结合蛋白(L-FABP)对慢加急性肝衰竭短期预后的预测价值

DOI: 10.12449/JCH240821

Value of urinary liver fatty acid-binding protein in predicting the short-term prognosis of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure

-

摘要:

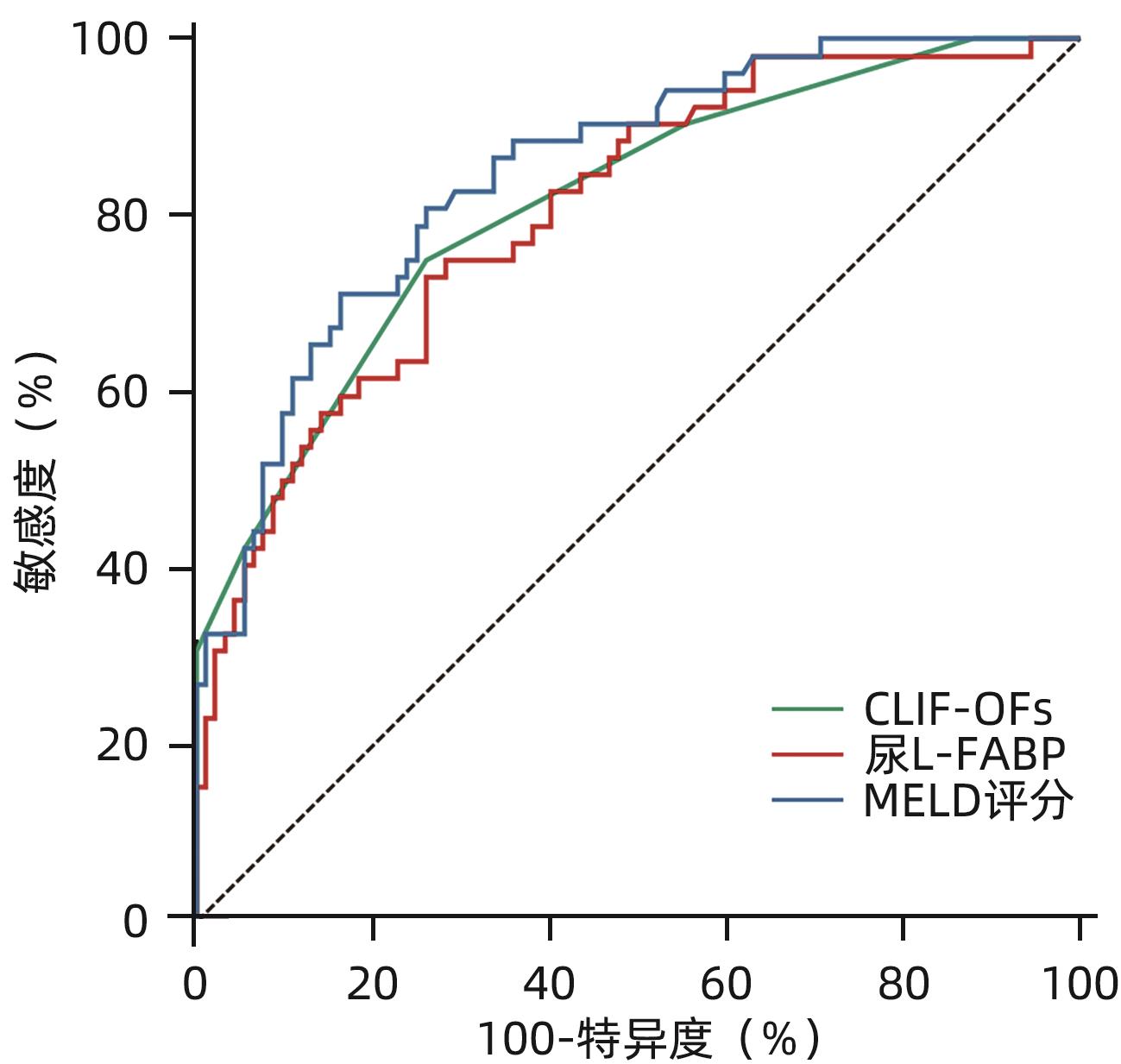

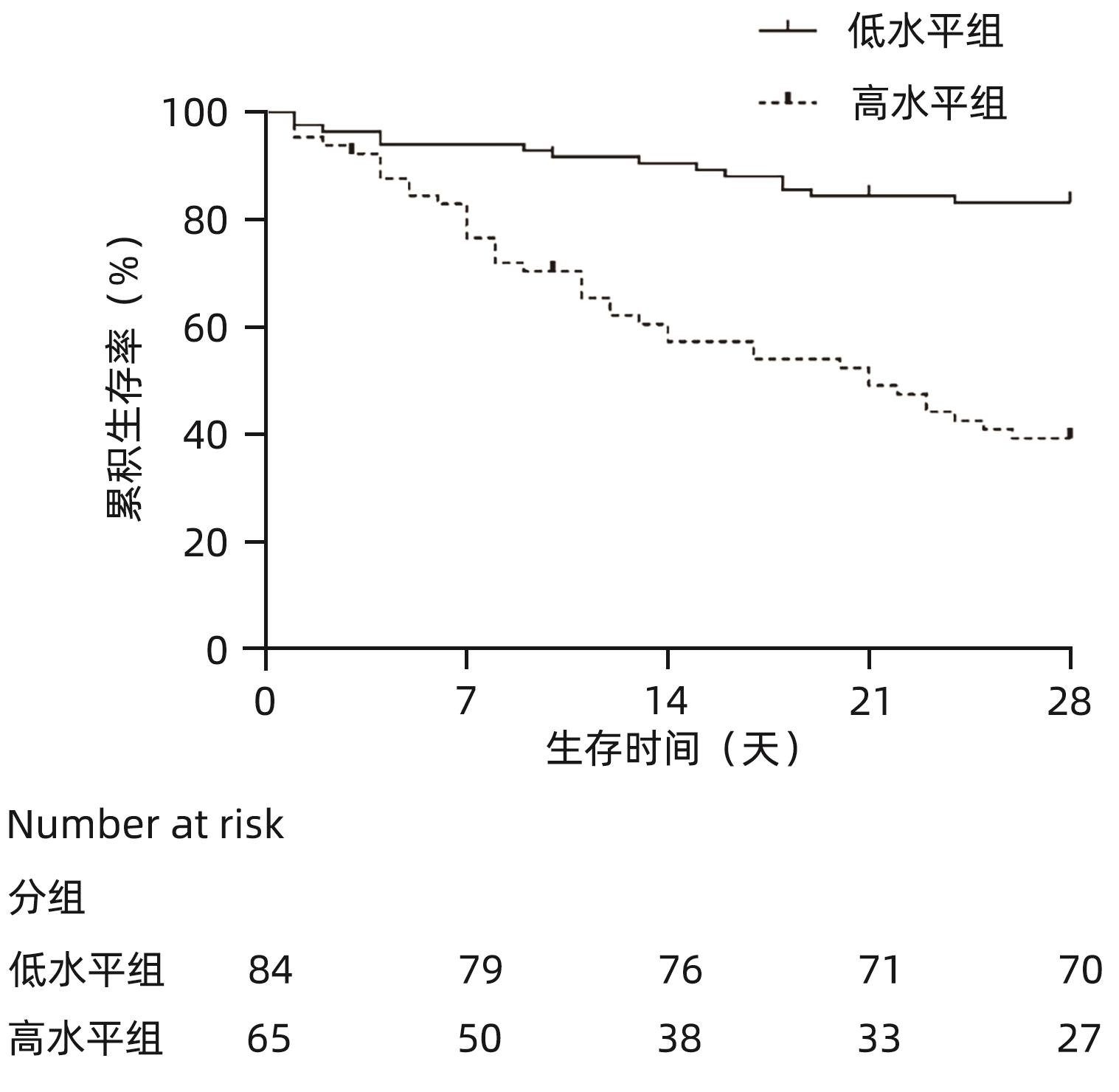

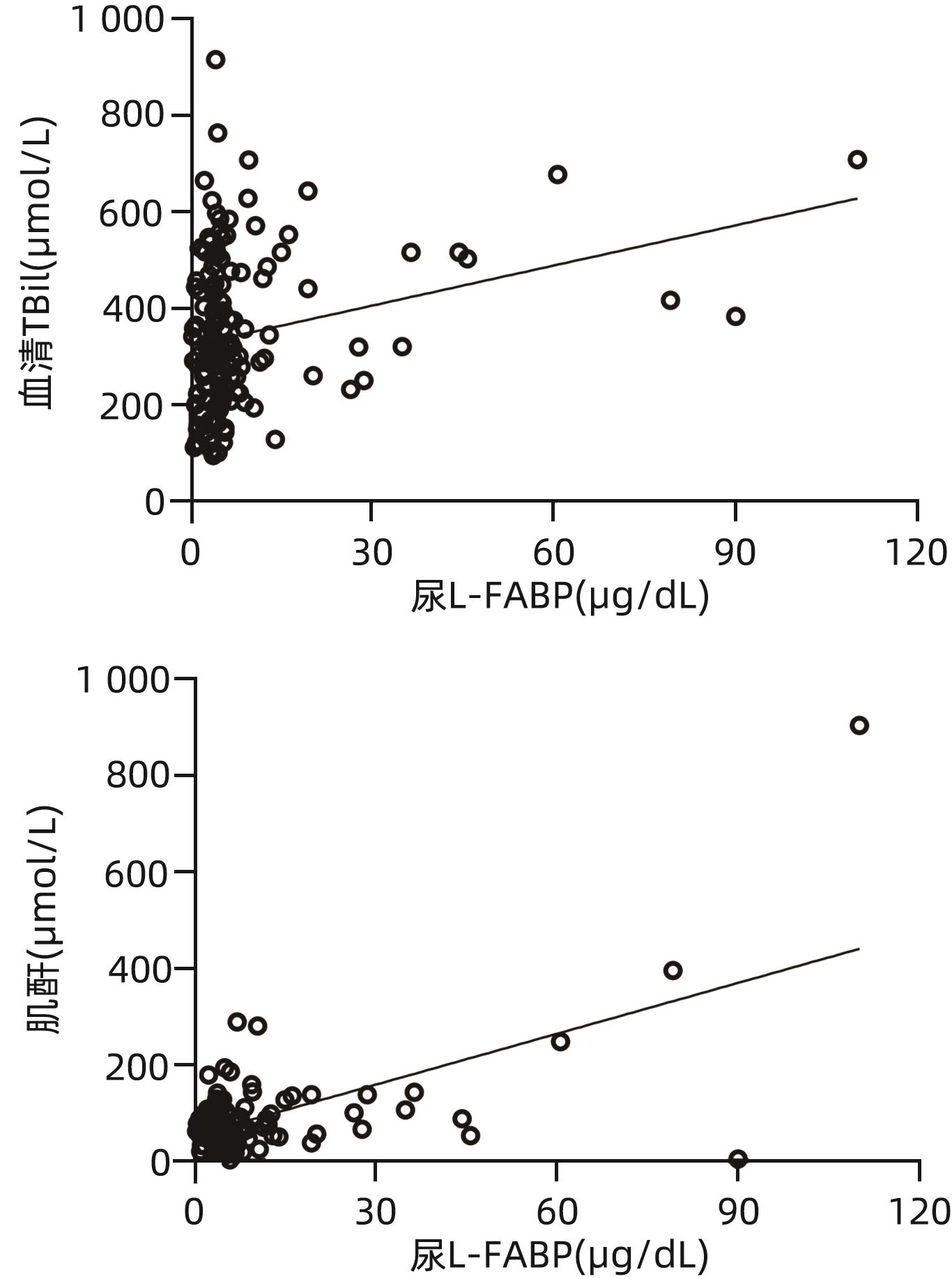

目的 探讨肝型脂肪酸结合蛋白(L-FABP)对慢加急性肝衰竭(ACLF)患者严重程度及短期预后的预测价值。 方法 研究对象149例来自于一个评估ACLF患者血小板功能的前瞻性、多中心队列,根据入院28天预后分为生存组(n=97)与死亡组(n=52)。分析患者的性别、年龄、病因以及入院后24 h内的血常规、生化指标、器官衰竭情况并检测尿液及血液中L-FABP水平。正态分布的计量资料2组间比较使用成组t检验;非正态资料分布的计量资料2组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料2组间比较采用χ2检验。Spearman相关性检验评估尿L-FABP与肝衰竭相关指标的相关性。绘制受试者工作特征曲线(ROC曲线)评价CLIF-OFs、MELD评分和尿L-FABP对于ACLF患者短期预后的预测价值;通过Kaplan-Meier分析尿L-FABP高水平组与低水平组患者短期死亡情况;采用Cox风险比例模型分析各因素对ACLF短期预后的影响。 结果 两组患者在白细胞计数、血清TBil、INR、CLIF-OFs、MELD评分和尿L-FABP水平;脑衰竭、肝衰竭、凝血衰竭、肾脏衰竭、呼吸衰竭的比例方面差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)。相关性分析结果显示,尿L-FABP与血清TBil呈显著正相关(r=0.225,P=0.006)。尿L-FABP水平预测28天预后的ROC曲线下面积(AUC)为0.804(95%CI:0.729~0.865,P<0.001),截断值为4.779 µg/dL(敏感度为73.08%,特异度为73.91%,约登指数为0.469 9)。Kaplan-Meier生存分析发现,相比于尿L-FABP低水平组(尿L-FABP≤4.779 µg/dL),尿L-FABP高水平组(尿L-FABP>4.779 µg/dL)28天生存率显著降低(P<0.001)。Cox风险比例模型分析发现,血清TBil(HR=1.003,95%CI:1.001~1.004)、CLIF-OFs(HR=2.283,95%CI:1.814~2.873)和高尿L-FABP水平(HR=4.568,95%CI:2.424~8.608)为ACLF短期预后的独立危险因素(P值均<0.05)。 结论 高尿L-FABP水平可作为ACLF短期预后的临床预测指标,需扩大样本量进一步验证其预测价值。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the value of liver fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) in predicting the severity and short-term prognosis of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Methods A total of 149 patients with ACLF were selected from a prospective multicenter cohort assessing the platelet function of ACLF patients, and according to the 28-day prognosis after admission, they were divided into survival group with 97 patients and death group with 52 patients. The patients were analyzed in terms of sex, age, etiology, and blood routine, biochemical parameters, and organ failure status within 24 hours after admission, and the level of L-FABP in urine and blood was measured. The independent-samples t test was used for comparison of normally distributed continuous data between two groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed continuous data between two groups; the chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between two groups. The Spearman test was used to evaluate the correlation between urinary L-FABP and indicators for liver failure. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to assess the value of CLIF-OFs, MELD score, and urinary L-FABP in predicting the short-term prognosis of ACLF patients; the Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to evaluate short-term mortality in the high urinary L-FABP group and the low urinary L-FABP group; the Cox proportional hazards model was used to investigate the association of each factor with the short-term prognosis of ACLF. Results There were significant differences between the two groups in white blood cell count, serum total bilirubin (TBil), international normalized ratio, CLIF-OFs, MELD score, urinary L-FABP level, and the proportion of patients with cerebral failure, liver failure, coagulation failure, renal failure, or respiratory failure (all P<0.05). The Spearman correlation analysis showed that urinary L-FABP was significantly positively correlated with serum TBil (r=0.225, P=0.006). Urinary L-FABP level had an area under the ROC curve of 0.804 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.729 — 0.865, P<0.001) and a cut-off value of 4.779 µg/dL, with a sensitivity of 73.08%, a specificity of 73.91%, and a Youden index of 0.469 9. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that compared with the low urinary L-FABP group (urinary L-FABP≤4.779 µg/dL), the high urinary L-FABP group (urinary L-FABP>4.779 µg/dL) had a significantly lower 28-day survival rate (P<0.001). The Cox proportional hazards model analysis showed that serum TBil (hazard ratio [HR]=1.003, 95%CI: 1.001 — 1.004, P<0.05), CLIF-OFs (HR=2.283, 95%CI: 1.814 — 2.873, P<0.05), and high urinary L-FABP level (HR=4.568, 95%CI: 2.424 — 8.608, P<0.05) were independent risk factors for the short-term prognosis of ACLF. Conclusion High urinary L-FABP level can be used as a clinical indicator for predicting the short-term prognosis of ACLF, and further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to evaluate its predictive value. -

表 1 CLIF-OFs系统

Table 1. CLIF-OFs system

器官/系统 1分 2分 3分 肝脏 TBil<6 mg/dL 6 mg/dL≤TBil<12 mg/dL TBil≥12 mg/dL 肾脏 肌酐<2 mg/dL 2 mg/dL≤肌酐<3.5 mg/dL 肌酐≥3.5 mg/dL或肾脏替代治疗 脑(肝性脑病分级) 0级 Ⅰ~Ⅱ级 Ⅲ~Ⅳ级 凝血 INR<2.0 2.0≤INR<2.5 INR≥2.5 循环 平均动脉压≥70 mmHg 平均动脉压<70 mmHg 使用血管活性药物 呼吸 PaO2/FiO2>300 或SPO2/FiO2>357 200<PaO2/FiO2≤300

或214<SPO2/FiO2≤357

PaO2/FiO2≤200 或SPO2/FiO2≤214 注:PaO2/FiO2,氧分压/氧浓度;SPO2/FiO2,血氧饱和度/氧浓度。

表 2 患者的基线资料

Table 2. Baseline data of the patients

指标 生存组(n=97) 死亡组(n=52) 统计值 P值 年龄(岁) 48±12 52±13 t=1.883 0.062 男性[例(%)] 81(83.5) 39(75.0) χ2=1.562 0.211 病因[例(%)] χ2=4.378 0.217 乙型肝炎 69(71.1) 33(63.5) 乙型肝炎合并其他 8(8.2) 9(17.3) 酒精性肝病 9(9.3) 2(3.8) 其他1) 11(11.3) 8(15.4) 白细胞计数(×109/L) 6.3(4.3~7.9) 8.8(6.2~14.7) Z=-4.514 <0.001 ALT(U/L) 198.0(49.0~433.0) 142.0(44.3~410.5) Z=-0.677 0.498 AST(U/L) 153.0(74.0~339.0) 192.5(90.3~375.3) Z=-1.033 0.301 TBil(µmol/L) 289.6(204.9~360.2) 430.9(323.9~533.3) Z=-5.386 <0.001 Alb(g/L) 31.0(27.9~34.8) 30.3(26.9~34.1) Z=-0.797 0.426 INR 2.1(1.8~2.5) 2.9(2.3~3.6) Z=-5.126 <0.001 肌酐(µmol/L) 66.0(53.4~82.0) 78.0(52.7~121.8) Z=-1.631 0.103 脑衰竭[例(%)] 0(0.0) 11(21.2) χ2=10.262 <0.001 肝衰竭[例(%)] 73(75.3) 50(96.2) χ2=22.155 0.001 凝血衰竭[例(%)] 26(26.8) 37(71.2) χ2=27.284 <0.001 肾脏衰竭[例(%)] 2(2.1) 6(11.5) χ2=5.984 0.039 呼吸衰竭[例(%)] 0(0.0) 4(7.7) χ2=7.667 0.014 循环衰竭[例(%)] 3(3.1) 2(3.8) χ2=0.059 >0.05 CLIF-OFs 9(8~10) 10(9~12) Z=-6.318 <0.001 MELD评分 26.2±3.7 32.8±5.9 t=7.240 <0.001 血浆L-FABP(µg/dL) 3.0(1.8~6.1) 3.6(1.6~9.6) Z=-0.781 0.435 尿L-FABP(µg/dL) 3.8(2.2~5.2) 6.7(4.6~12.9) Z=-5.733 <0.001 注:1)生存组包含2例自身免疫性肝病患者、1例代谢性肝病患者、8例肝硬化原因不明患者;死亡组包含1例丙型肝炎患者、2例药物性肝损伤患者和5例肝硬化原因不明患者。

表 3 影响ACLF患者预后的单因素和多因素分析

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in ACLF patients

指标 单因素分析 多因素分析 HR 95%CI P值 HR 95%CI P值 年龄(岁) 1.019 0.996~1.043 0.105 性别 1.464 0.781~2.744 0.235 病因 0.084 乙型肝炎 乙型肝炎合并其他 0.701 0.323~1.518 0.367 酒精性肝病 1.617 0.623~4.194 0.323 其他 0.355 0.075~1.675 0.191 白细胞计数(×109/L) 1.019 1.007~1.032 0.002 ALT(U/L) 1.000 1.000~1.000 0.834 AST(U/L) 1.000 1.000~1.001 0.066 TBil(µmol/L) 1.004 1.003~1.006 <0.001 1.003 1.001~1.004 0.001 Alb(g/L) 0.984 0.934~1.036 0.532 INR 2.367 1.865~3.004 <0.001 肌酐(µmol/L) 1.002 1.001~1.004 0.006 MELD评分 1.162 1.121~1.203 <0.001 CLIF-OFs 2.323 1.906~2.832 <0.001 2.283 1.814~2.873 <0.001 尿L-FABP ≤4.779 µg/dL 1.000 1.000 >4.779 µg/dL 4.834 2.612~8.947 <0.001 4.568 2.424~8.608 <0.001 表 4 尿L-FABP水平与ACLF患者器官衰竭和AKI的关系

Table 4. The relationship between urinary L-FABP levels and organ failure or acute kidney injury in ACLF patients

项目 低水平组(n=84) 高水平组(n=65) 是 [例(%)] 否 [例(%)] 是 [例(%)] 否 [例(%)] 器官衰竭 循环 3(3.6) 81(96.4) 2(3.1) 63(96.9) 呼吸 2(2.4) 82(97.6) 2(3.1) 63(96.9) 脑 3(3.6) 81(96.4) 8(12.3) 57(87.7) 肝脏 63(75.0) 21(25.0) 60(92.3) 5(7.7) 肾脏 1(1.2) 83(98.8) 7(10.8) 58(89.2) 凝血 28(33.3) 56(66.7) 35(53.8) 30(46.2) AKI 7(8.3) 77(91.7) 16(24.6) 49(75.4) -

[1] ZHANG Q, HAN T. Prognostic evaluation of acute-on-chronic liver failure[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2023, 39( 10): 2301- 2306. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.10.006.张倩, 韩涛. 慢加急性肝衰竭的预后评价[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2023, 39( 10): 2301- 2306. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.10.006. [2] EGUCHI A, IWASA M. The role of elevated liver-type fatty acid-binding proteins in liver diseases[J]. Pharm Res, 2021, 38( 1): 89- 95. DOI: 10.1007/s11095-021-02998-x. [3] WANG NN, XU LZ, WANG YP. Progress in liver type fatty acid binding protein[J]. Chin Bull Life Sci, 2012, 24( 2): 139- 144. DOI: 10.13376/j.cbls/2012.02.002.王南南, 徐力致, 王亚平. 肝型脂肪酸结合蛋白研究进展[J]. 生命科学, 2012, 24( 2): 139- 144. DOI: 10.13376/j.cbls/2012.02.002. [4] WEN YM, PARIKH CR. Current concepts and advances in biomarkers of acute kidney injury[J]. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci, 2021, 58( 5): 354- 368. DOI: 10.1080/10408363.2021.1879000. [5] PRIYADARSHINI G, RAJAPPA M. Predictive markers in chronic kidney disease[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2022, 535: 180- 186. DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2022.08.018. [6] JUANOLA A, GRAUPERA I, ELIA C, et al. Urinary L-FABP is a promising prognostic biomarker of ACLF and mortality in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 76( 1): 107- 114. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.08.031. [7] JIANG XH, CHAI SQ, HUANG Y, et al. Design for a multicentre prospective cohort for the assessment of platelet function in patients with hepatitis-B-virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure[J]. Clin Epidemiol, 2022, 14: 997- 1011. DOI: 10.2147/CLEP.S376068. [8] SARIN SK, CHOUDHURY A, SHARMA MK, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver(APASL): An update[J]. Hepatol Int, 2019, 13( 4): 353- 390. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3. [9] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69( 2): 406- 460. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [10] ANGELI P, GINÈS P, WONG F, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 62( 4): 968- 974. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.029. [11] BLEI AT, CÓRDOBA J. Hepatic encephalopathy[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2001, 96( 7): 1968- 1976. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. [12] KULKARNI AV, SHARMA M, KUMAR P, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein as a predictor of outcome in alcohol-induced acute-on-chronic liver failure[J]. J Clin Exp Hepatol, 2021, 11( 2): 201- 208. DOI: 10.1016/j.jceh.2020.07.010. [13] CHEN AP, TANG YC, DAVIS V, et al. Liver fatty acid binding protein(L-Fabp) modulates murine stellate cell activation and diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 57( 6): 2202- 2212. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26318. [14] LIN JG, ZHENG SZ, ATTIE AD, et al. Perilipin 5 and liver fatty acid binding protein function to restore quiescence in mouse hepatic stellate cells[J]. J Lipid Res, 2018, 59( 3): 416- 428. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.M077487. [15] PAWLAK M, LEFEBVRE P, STAELS B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 62( 3): 720- 733. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.039. [16] LÓPEZ-VICARIO C, CHECA A, URDANGARIN A, et al. Targeted lipidomics reveals extensive changes in circulating lipid mediators in patients with acutely decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73( 4): 817- 828. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.046. [17] ZHANG Y, LIU KC, HASSAN HM, et al. Liver fatty acid binding protein deficiency provokes oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis-mediated hepatotoxicity induced by pyrazinamide in zebrafish larvae[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016, 60( 12): 7347- 7356. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01693-16. [18] VOTH M, VERBOKET R, HENRICH D, et al. L-FABP and NGAL are novel biomarkers for detection of abdominal injury and hemorrhagic shock[J]. Injury, 2023, 54( 5): 1246- 1256. DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2023.01.001. [19] LI Q, WANG J, LU MJ, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure from chronic-hepatitis-B, who is the behind scenes[J]. Front Microbiol, 2020, 11: 583423. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.583423. [20] EGUCHI A, HASEGAWA H, IWASA M, et al. Serum liver-type fatty acid-binding protein is a possible prognostic factor in human chronic liver diseases from chronic hepatitis to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2019, 3( 6): 825- 837. DOI: 10.1002/hep4.1350. [21] MCMAHON BA, MURRAY PT. Urinary liver fatty acid-binding protein: Another novel biomarker of acute kidney injury[J]. Kidney Int, 2010, 77( 8): 657- 659. DOI: 10.1038/ki.2010.5. -

PDF下载 ( 964 KB)

PDF下载 ( 964 KB)

下载:

下载: