胰源性糖尿病的发病机制探析

DOI: 10.12449/JCH240834

利益冲突声明:本文不存在任何利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:王晨晓、王希望负责文献检索,撰写论文;王莹、金晶晶参与收集数据,资料整理;刘江凯负责修改论文;燕树勋、王晓负责拟定写作思路,指导撰写文章并最后定稿。

-

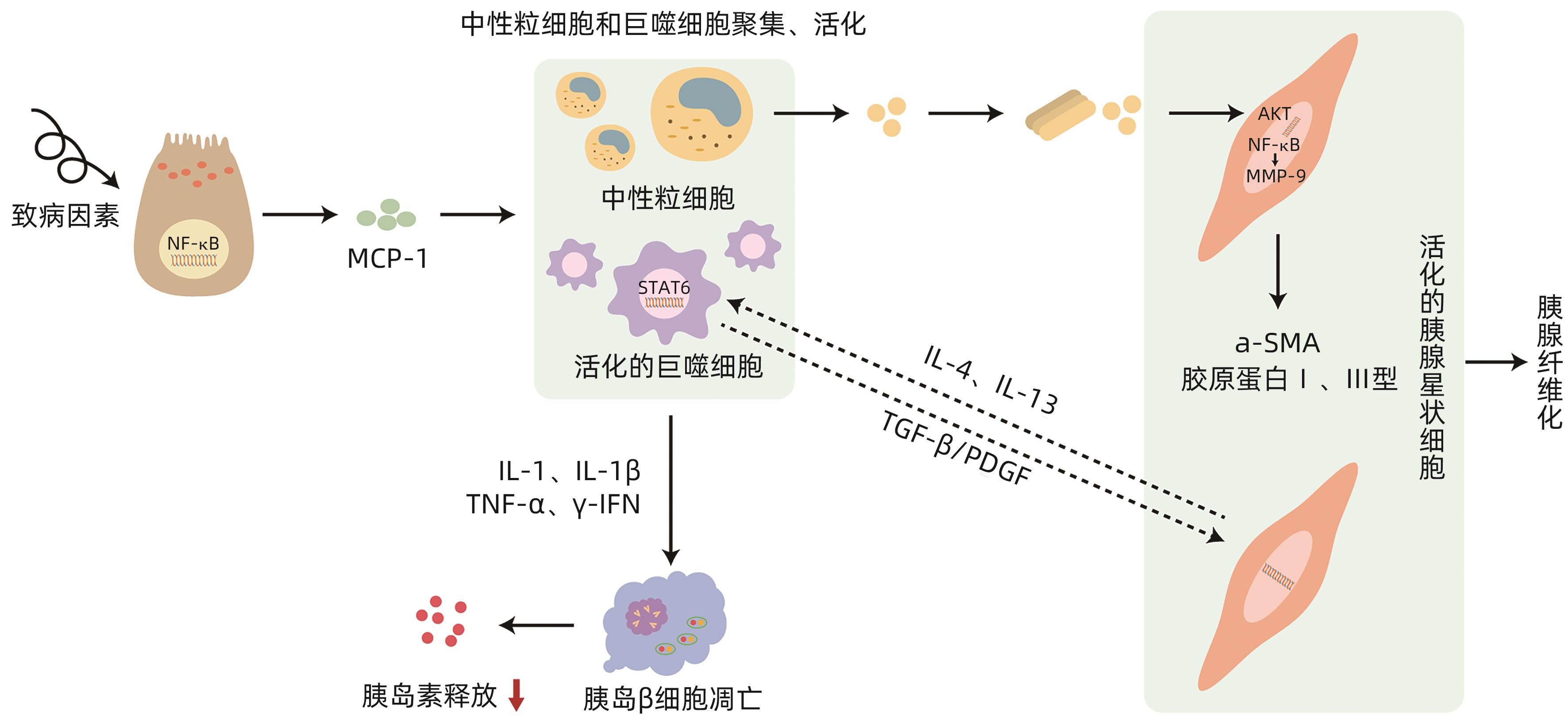

摘要: 胰源性糖尿病是一种继发于胰腺外分泌疾病的糖尿病,2014年被美国糖尿病学会正式命名,慢性胰腺炎和胰腺癌是其最主要的发病原因。该病的发病机制尚不完全明确,系统的治疗方案尚未形成,因此国内外关于胰源性糖尿病的误诊率极高,且研究发现该型糖尿病患者与2型糖尿病相比具有更高的死亡和再入院风险,这无疑对患者的健康和临床治疗充满挑战。因此充分了解、早期正确识别及诊断胰源性糖尿病,对降低该病的致残率与病死率具有重要意义。本文对胰源性糖尿病可能的发病机制进行阐述与分析。Abstract: Pancreatogenic diabetes is a type of diabetes secondary to pancreatic exocrine disease, and it was officially named by American Diabetes Association in 2014. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer are the most common causes of pancreatogenic diabetes. The pathogenesis of this disease remains unclear, and there is still a lack of systematic treatment regimens, which leads to the extremely high misdiagnosis rate of pancreatogenic diabetes in China and globally. In addition, studies have shown that compared with patients with type 2 diabetes, patients with pancreatogenic diabetes tend to have higher risks of death and readmission, which brings great challenges to the health and clinical treatment of patients. Therefore, the comprehensive understanding and early accurate identification and diagnosis of pancreatogenic diabetes are of great significance in reducing the disability and mortality rates of this disease. This article elaborates on the possible pathogenesis of pancreatogenic diabetes.

-

Key words:

- Pancreatic Diabetes /

- Pathologic Processes /

- Diagnosis

-

[1] MAKUC J. Management of pancreatogenic diabetes: Challenges and solutions[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2016, 9: 311- 315. DOI: 10.2147/DMSO.S99701. [2] PETROV MS, BASINA M. Diagnosis of endocrine disease: Diagnosing and classifying diabetes in diseases of the exocrine pancreas[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2021, 184( 4): R151- R163. DOI: 10.1530/EJE-20-0974. [3] VONDERAU JS, DESAI CS. Type 3c: Understanding pancreatogenic diabetes[J]. JAAPA, 2022, 35( 11): 20- 24. DOI: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000885140.47709.6f. [4] CHO J, SCRAGG R, PETROV MS. Risk of mortality and hospitalization after post-pancreatitis diabetes mellitus vs type 2 diabetes mellitus: A population-based matched cohort study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2019, 114( 5): 804- 812. DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000225. [5] SANTOS R, COLEMAN HG, CAIRNDUFF V, et al. Clinical prediction models for pancreatic cancer in general and at-risk populations: A systematic review[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2023, 118( 1): 26- 40. DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002022. [6] American Diabetes Association. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44( Suppl 1): S15- S33. DOI: 10.2337/dc21-S002. [7] LI GQ, SUN JF, ZHANG J, et al. Identification of inflammation-related biomarkers in diabetes of the exocrine pancreas with the use of weighted gene co-expression network analysis[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2022, 13: 839865. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2022.839865. [8] POLLARD JW. The yolk sac feeds pancreatic tumors[J]. Immunity, 2017, 47( 2): 217- 218. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.021. [9] ZHANG H, CAI D, BAI X. Macrophages regulate the progression of osteoarthritis[J]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2020, 28( 5): 555- 561. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.007. [10] SWAIN SM, ROMAC JMJ, SHAHID RA, et al. TRPV4 channel opening mediates pressure-induced pancreatitis initiated by Piezo1 activation[J]. J Clin Invest, 2020, 130( 5): 2527- 2541. DOI: 10.1172/JCI134111. [11] PALLAGI P, MADÁCSY T, VARGA Á, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ signalling in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: Recent advances and translational perspectives[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21( 11): 4005. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21114005. [12] ZHANG Y, ZHANG WQ, LIU XY, et al. Immune cells and immune cell-targeted therapy in chronic pancreatitis[J]. Front Oncol, 2023, 13: 1151103. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1151103. [13] LIU SY, SZATMARY P, LIN JW, et al. Circulating monocytes in acute pancreatitis[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 1062849. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1062849. [14] SALUJA A, DUDEJA V, DAWRA R, et al. Early intra-acinar events in pathogenesis of pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156( 7): 1979- 1993. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.268. [15] KRATOCHVILL F, NEALE G, HAVERKAMP JM, et al. TNF counterbalances the emergence of M2 tumor macrophages[J]. Cell Rep, 2015, 12( 11): 1902- 1914. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.033. [16] PAVAN KUMAR P, RADHIKA G, RAO GV, et al. Interferon γ and glycemic status in diabetes associated with chronic pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2012, 12( 1): 65- 70. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2011.12.005. [17] CASU AN, GRIPPO PJ, WASSERFALL C, et al. Evaluating the immunopathogenesis of diabetes after acute pancreatitis in the diabetes RElated to acute pancreatitis and its mechanisms study: From the type 1 diabetes in acute pancreatitis consortium[J]. Pancreas, 2022, 51( 6): 580- 585. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000002076. [18] WEN L, JAVED TA, DOBBS AK, et al. The protective effects of calcineurin on pancreatitis in mice depend on the cellular source[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 159( 3): 1036- 1050. e 8. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.051. [19] JAGANJAC M, CIPAK A, SCHAUR RJ, et al. Pathophysiology of neutrophil-mediated extracellular redox reactions[J]. Front Biosci(Landmark Ed), 2016, 21( 4): 839- 855. DOI: 10.2741/4423. [20] XIA D, HALDER B, GODOY C, et al. NADPH oxidase 1 mediates caerulein-induced pancreatic fibrosis in chronic pancreatitis[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2020, 147: 139- 149. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.11.034. [21] CANNON A, THOMPSON CM, BHATIA R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of pancreatic myofibroblast activation in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[J]. J Gastroenterol, 2021, 56( 8): 689- 703. DOI: 10.1007/s00535-021-01800-4. [22] SCHMITZ-WINNENTHAL H, PIETSCH DH, SCHIMMACK S, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with disease-specific regulatory T-cell responses[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 138( 3): 1178- 1188. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.011. [23] ZHOU Q, TAO XF, XIA SL, et al. T lymphocytes: A promising immunotherapeutic target for pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer?[J]. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 382. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00382. [24] GLAUBITZ J, WILDEN A, GOLCHERT J, et al. In mouse chronic pancreatitis CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells control pancreatic fibrosis by suppression of the type 2 immune response[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13( 1): 4502. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-32195-2. [25] CHANG M, CHEN WJ, XIA RT, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells and the targeted therapeutic strategies in chronic pancreatitis[J]. Molecules, 2023, 28( 14): 5586. DOI: 10.3390/molecules28145586. [26] RABIEE A, GALIATSATOS P, SALAS-CARRILLO R, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide administration enhances insulin sensitivity and reduces the insulin requirement of patients on insulin pump therapy[J]. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2011, 5( 6): 1521- 1528. DOI: 10.1177/193229681100500629. [27] APTE M, PIROLA R, WILSON J. The fibrosis of chronic pancreatitis: New insights into the role of pancreatic stellate cells[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011, 15( 10): 2711- 2722. DOI: 10.1089/ars.2011.4079. [28] RAMAKRISHNAN P, LOH WM, GOPINATH SCB, et al. Selective phytochemicals targeting pancreatic stellate cells as new anti-fibrotic agents for chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2020, 10( 3): 399- 413. DOI: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.11.008. [29] BYNIGERI RR, JAKKAMPUDI A, JANGALA R, et al. Pancreatic stellate cell: Pandora’s box for pancreatic disease biology[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2017, 23( 3): 382- 405. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i3.382. [30] ARUMUGAM T, BRANDT W, RAMACHANDRAN V, et al. Trefoil factor 1 stimulates both pancreatic cancer and stellate cells and increases metastasis[J]. Pancreas, 2011, 40( 6): 815- 822. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821f6927. [31] LEE SH, PARK SY, CHOI CS. Insulin resistance: From mechanisms to therapeutic strategies[J]. Diabetes Metab J, 2022, 46( 1): 15- 37. DOI: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0280. [32] OLESEN SS, SVANE HML, NICOLAISEN SK, et al. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of postpancreatitis diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study from the Danish nationwide DD2 cohort[J]. J Diabetes, 2021, 13( 12): 960- 974. DOI: 10.1111/1753-0407.13210. [33] ASLAM M, VIJAYASARATHY K, TALUKDAR R, et al. Reduced pancreatic polypeptide response is associated with early alteration of glycemic control in chronic pancreatitis[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2020, 160: 107993. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107993. [34] HENNIG R, KEKIS PB, FRIESS H, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide in pancreatitis[J]. Peptides, 2002, 23( 2): 331- 338. DOI: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00605-2. [35] GOODARZI MO, PETROV MS. Diabetes of the exocrine pancreas: Implications for pharmacological management[J]. Drugs, 2023, 83( 12): 1077- 1090. DOI: 10.1007/s40265-023-01913-5. [36] GOLDSTEIN JA, KIRWIN JD, SEYMOUR NE, et al. Reversal of in vitro hepatic insulin resistance in chronic pancreatitis by pancreatic polypeptide in the rat[J]. Surgery, 1989, 106( 6): 1128-1132; discussion 1132-1133. [37] CAI DS, YUAN MS, FRANTZ DF, et al. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB[J]. Nat Med, 2005, 11( 2): 183- 190. DOI: 10.1038/nm1166. [38] HEO YJ, CHOI SE, JEON JY, et al. Visfatin induces inflammation and insulin resistance via the NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways in hepatocytes[J]. J Diabetes Res, 2019, 2019: 4021623. DOI: 10.1155/2019/4021623. [39] SAH RP, NAGPAL SJ, MUKHOPADHYAY D, et al. New insights into pancreatic cancer-induced paraneoplastic diabetes[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 10( 7): 423- 433. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.49. [40] YARIBEYGI H, FARROKHI FR, BUTLER AE, et al. Insulin resistance: Review of the underlying molecular mechanisms[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2019, 234( 6): 8152- 8161. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.27603. [41] ZHOU XL, YOU SY. Rosiglitazone inhibits hepatic insulin resistance induced by chronic pancreatitis and IKK-β/NF-κB expression in liver[J]. Pancreas, 2014, 43( 8): 1291- 1298. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000173. [42] WENTWORTH JM, ZHANG JG, BANDALA-SANCHEZ E, et al. Interferon-gamma released from omental adipose tissue of insulin-resistant humans alters adipocyte phenotype and impairs response to insulin and adiponectin release[J]. Int J Obes, 2017, 41( 12): 1782- 1789. DOI: 10.1038/ijo.2017.180. [43] REHMAN K, AKASH MSH, LIAQAT A, et al. Role of interleukin-6 in development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr, 2017, 27( 3): 229- 236. DOI: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2017019712. [44] AKBARI M, HASSAN-ZADEH V. IL-6 signalling pathways and the development of type 2 diabetes[J]. Inflammopharmacology, 2018, 26( 3): 685- 698. DOI: 10.1007/s10787-018-0458-0. [45] DOU L, ZHAO T, WANG LL, et al. MiR-200s contribute to interleukin-6(IL-6)-induced insulin resistance in hepatocytes[J]. J Biol Chem, 2013, 288( 31): 22596- 22606. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.423145. [46] DOU L, WANG SY, SUI XF, et al. MiR-301a mediates the effect of IL-6 on the AKT/GSK pathway and hepatic glycogenesis by regulating PTEN expression[J]. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2015, 35( 4): 1413- 1424. DOI: 10.1159/000373962. [47] CHEANG JY, MOYLE PM. Glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1)-based therapeutics: Current status and future opportunities beyond type 2 diabetes[J]. ChemMedChem, 2018, 13( 7): 662- 671. DOI: 10.1002/cmdc.201700781. [48] TUDURÍ E, LÓPEZ M, DIÉGUEZ C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 analogs and their effects on pancreatic islets[J]. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 27( 5): 304- 318. DOI: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.03.004. [49] DRUCKER DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1[J]. Cell Metab, 2018, 27( 4): 740- 756. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [50] ZHOU Z, SUN B, YU DS, et al. Gut microbiota: An important player in type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022, 12: 834485. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.834485. [51] TILG H, ZMORA N, ADOLPH TE, et al. The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2020, 20( 1): 40- 54. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-019-0198-4. [52] TAO J, CHEEMA H, KESH K, et al. Chronic pancreatitis in a caerulein-induced mouse model is associated with an altered gut microbiome[J]. Pancreatology, 2022, 22( 1): 30- 42. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.12.003. [53] ARON-WISNEWSKY J, WARMBRUNN MV, NIEUWDORP M, et al. Metabolism and metabolic disorders and the microbiome: The intestinal microbiota associated with obesity, lipid metabolism, and metabolic health-pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies[J]. Gastroenterology, 2021, 160( 2): 573- 599. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.057. [54] TALUKDAR R, SARKAR P, JAKKAMPUDI A, et al. The gut microbiome in pancreatogenic diabetes differs from that of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes[J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11( 1): 10978. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-90024-w. [55] JANDHYALA SM, MADHULIKA A, DEEPIKA G, et al. Altered intestinal microbiota in patients with chronic pancreatitis: Implications in diabetes and metabolic abnormalities[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 43640. DOI: 10.1038/srep43640. [56] ZOU WB, TANG XY, ZHOU DZ, et al. SPINK1, PRSS1, CTRC, and CFTR genotypes influence disease onset and clinical outcomes in chronic pancreatitis[J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2018, 9( 11): 204. DOI: 10.1038/s41424-018-0069-5. [57] CHEN JM, FÉREC C. Genetics and pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis: The 2012 update[J]. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol, 2012, 36( 4): 334- 340. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.05.003. [58] MASSON E, CHEN JM, AUDRÉZET MP, et al. A conservative assessment of the major genetic causes of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis: Data from a comprehensive analysis of PRSS1, SPINK1, CTRC and CFTR genes in 253 young French patients[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8( 8): e73522. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073522. [59] LIU QC, ZHUANG ZH, ZENG K, et al. Prevalence of pancreatic diabetes in patients carrying mutations or polymorphisms of the PRSS1 gene in the Han population[J]. Diabetes Technol Ther, 2009, 11( 12): 799- 804. DOI: 10.1089/dia.2009.0051. -

PDF下载 ( 941 KB)

PDF下载 ( 941 KB)

下载:

下载: