丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿患者再代偿的影响因素分析

DOI: 10.12449/JCH250212

Influencing factors for recompensation in patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis

-

摘要:

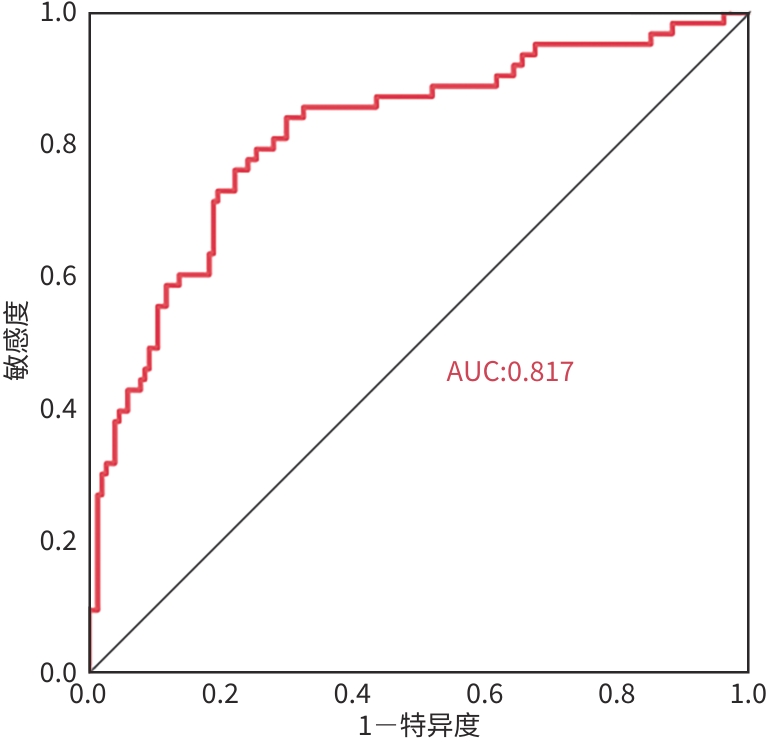

目的 研究丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿期患者再代偿发生的影响因素,建立预测模型。 方法 选取2019年1月—2022年12月在昆明市第三人民医院住院诊断为丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿的患者217例,至少1年之内再住院无门静脉高压相关并发症即再代偿组(n=63),未再代偿者为对照组(n=154)。收集相关临床资料,对可能影响再代偿发生的因素进行单因素及多因素分析。计量资料符合正态分布的两组间比较采用成组t检验,不符合正态分布的两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。计数资料两组间比较采用χ²检验或Fisher’s确切概率法。运用二元Logistic回归模型分析丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿患者再代偿发生的影响因素,采用受试者操作特征曲线(ROC曲线)评价模型的预测效能。 结果 217例丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿期患者中63例发生再代偿(29.03%)。再代偿组与对照组相比,HIV史(χ²=4.566,P=0.034)、部分脾栓塞史(χ²=6.687,P=0.014)、Child-Pugh 评分(χ²=11.978,P=0.003)、腹水分级(χ²=14.229,P<0.001)、Alb(t=4.063,P<0.001)、前白蛋白(Z=-3.077,P=0.002)、HDL(t=2.854,P=0.011)、超敏C反应蛋白(Z=-2.447,P=0.014)、凝血酶原时间(Z=-2.441,P=0.015)、CEA(Z=-2.113,P=0.035)、AFP(Z=-2.063,P=0.039)、CA125(Z=-2.270,P=0.023)、三碘甲状腺素原氨酸(Z=-3.304,P<0.001)、甲状腺素(Z=-2.221,P=0.026)、CD45+(Z=-2.278,P=0.023)、IL-5(Z=-2.845,P=0.004)、TNF-α(Z=-2.176,P=0.030)、门静脉宽度(Z=-5.283,P=0.005)差异均有统计学意义。多因素分析结果显示,部分脾栓塞史(OR=3.064,P=0.049)、HIV史(OR=0.195,P=0.027)、少量腹水(OR=3.390,P=0.017)、AFP(OR=1.003,P=0.004)及门静脉宽度(OR=0.600,P<0.001)为丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿期发生再代偿的独立影响因素。ROC曲线结果显示HIV史、腹水分级、部分脾脏栓塞史、AFP、门静脉宽度、联合预测模型的曲线下面积依次为0.556、0.641、0.560、0.589、0.745、0.817。 结论 部分脾栓塞史、少量腹水及AFP水平升高的丙型肝炎肝硬化失代偿期患者更容易出现再代偿,有HIV史、门静脉宽度增加的患者不易出现再代偿。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the influencing factors for recompensation in patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis, and to establish a predictive model. Methods A total of 217 patients who were diagnosed with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis and were admitted to The Third People’s Hospital of Kunming l from January, 2019 to December, 2022 were enrolled, among whom 63 patients who were readmitted within at least 1 year and had no portal hypertension-related complications were enrolled as recompensation group, and 154 patients without recompensation were enrolled as control group. Related clinical data were collected, and univariate and multivariate analyses were performed for the factors that may affect the occurrence of recompensation. The independent-samples t test was used for comparison of normally distributed measurement data between two groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed measurement data between two groups; the chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical data between two groups. A binary Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the influencing factors for recompensation in patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the predictive performance of the model. Results Among the 217 patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis, 63 (29.03%) had recompensation. There were significant differences between the recompensation group and the control group in HIV history (χ2=4.566, P=0.034), history of partial splenic embolism (χ2=6.687, P=0.014), Child-Pugh classification (χ2=11.978, P=0.003), grade of ascites (χ2=14.229, P<0.001), albumin (t=4.063, P<0.001), prealbumin (Z=-3.077, P=0.002), high-density lipoprotein (t=2.854, P=0.011), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (Z=-2.447, P=0.014), prothrombin time (Z=-2.441, P=0.015), carcinoembryonic antigen (Z=-2.113, P=0.035), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (Z=-2.063, P=0.039), CA125 (Z=-2.270, P=0.023), TT3 (Z=-3.304, P<0.001), TT4 (Z=-2.221, P=0.026), CD45+ (Z=-2.278, P=0.023), interleukin-5 (Z=-2.845, P=0.004), tumor necrosis factor-α (Z=-2.176, P=0.030), and portal vein width (Z=-5.283, P=0.005). The multivariate analysis showed that history of partial splenic embolism (odds ratio [OR]=3.064, P=0.049), HIV history (OR=0.195, P=0.027), a small amount of ascites (OR=3.390, P=0.017), AFP (OR=1.003, P=0.004), and portal vein width (OR=0.600, P<0.001) were independent influencing factors for the occurrence of recompensation in patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis. The ROC curve analysis showed that HIV history, grade of ascites, history of partial splenic embolism, AFP, portal vein width, and the combined predictive model of these indices had an area under the ROC curve of 0.556, 0.641, 0.560, 0.589, 0.745, and 0.817, respectively. Conclusion For patients with decompensated hepatitis C cirrhosis, those with a history of partial splenic embolism, a small amount of ascites, and an increase in AFP level are more likely to experience recompensation, while those with a history of HIV and an increase in portal vein width are less likely to experience recompensation. -

Key words:

- Hepatitis C /

- Liver Cirrhosis /

- Recompensatory /

- Risk Factors

-

表 1 再代偿组与对照组一般资料比较

Table 1. Baseline characteristics between recompensation group and control group

项目 再代偿组(n=63) 对照组(n=154) 统计值 P值 男性[例(%)] 33(52.4) 102(66.2) χ²=3.650 0.065 年龄(岁) 50(43~56) 49(44~55) Z=-0.654 0.513 BMI(kg/m²) 22.22(21.11~24.46) 23.01(21.42~25.04) Z=-1.084 0.278 吸烟史[例(%)] 38(60.3) 105(68.2) χ²=1.230 0.274 糖尿病史[例(%)] 12(19.0) 26(16.9) χ²=0.145 0.844 高血压史[例(%)] 8(12.7) 19(12.3) χ²=0.005 >0.05 HIV史[例(%)] 4(6.3) 27(17.5) χ²=4.566 0.034 口服NSBB[例(%)] 9(14.3) 12(7.8) χ²=2.157 0.204 TIPS史[例(%)] 3(4.8) 3(1.9) χ²=0.360 0.236 内镜治疗史[例(%)] 12(19.0) 17(11.0) χ²=2.477 0.116 部分脾栓塞史[例(%)] 12(19.0) 11(7.1) χ²=6.687 0.014 饮酒史[例(%)] 31(49.2) 91(59.1) χ²=1.775 0.228 基因分型[例(%)] χ²=2.969 0.397 1 5(7.9) 11(7.1) 2 3(4.8) 7(4.5) 3 51(81.0) 133(86.4) 6 4(6.3) 3(1.9) Child-Pugh分级[例(%)] χ²=11.978 0.003 A级 16(25.4) 13(8.4) B级 34(54.0) 91(59.1) C级 13(20.6) 50(32.5) 腹水分级[例(%)] χ²=14.229 <0.001 无 14(22.2) 19(12.3) 少量 27(42.9) 38(24.7) 中大量 22(34.9) 97(62.9) 感染[例(%)] 23(36.5) 57(37.0) χ²=0.005 >0.05 HE[例(%)] 2(3.2) 10(6.5) χ²=0.516 0.270 HCV RNA阳性[例(%)] 49(77.8) 113(73.4) χ²=0.458 0.499 表 2 再代偿组与对照组的实验室检查结果比较

Table 2. Comparison of laboratory test between recompensation group and control group

指标 再代偿组(n=63) 对照组(n=154) 统计值 P值 WBC(×109/L) 3.67(2.57~5.42) 3.79(2.75~5.28) Z=-0.363 0.716 Neu(×109/L) 1.91(1.38~4.00) 2.27(1.54~3.70) Z=-0.457 0.647 Hb(×109/L) 122.00(94.00~137.00) 115.50(86.75~134.00) Z=-1.336 0.181 PLT(×109/L) 64.00(46.00~93.00) 65.00(43.00~92.25) Z=-0.320 0.749 TBil(mmol/L) 30.80(20.20~43.10) 31.80(19.75~49.53) Z=-0.653 0.514 ALT(U/L) 54.00(37.00~117.00) 59.50(41.75~96.50) Z=-0.318 0.750 AST(U/L) 44.00(24.00~77.00) 40.00(25.00~66.00) Z=-0.442 0.659 TP(g/L) 63.71±10.41 62.21±10.23 t=0.978 0.329 Alb(g/L) 32.20±5.81 28.68±5.83 t=4.063 <0.001 PA(mg/L) 109.90(85.40~144.00) 89.90(71.83~121.43) Z=-3.077 0.002 GGT(U/L) 55.00(36.00~137.00) 66.00(36.00~145.75) Z=-0.194 0.846 TC(mmol/L) 2.94(2.42~3.60) 2.80(2.15~3.45) Z=-1.388 0.165 LDL(mmol/L) 1.73(1.17~2.21) 1.41(1.03~1.99) Z=-1.659 0.970 HDL(mmol/L) 0.93±0.34 0.85±0.36 t=2.854 0.011 Cr(μmol/L) 59.00(54.00~70.00) 60.00(50.00~79.25) Z=-0.488 0.625 hs-CRP(mg/L) 1.49(0.63~4.53) 3.17(0.91~9.78) Z=-2.447 0.014 IL-6(pg/mL) 17.34(10.18~31.47) 18.75(11.33~37.73) Z=-1.136 0.256 PCT(ng/mL) 0.11(0.09~0.15) 0.13(0.09~0.23) Z=-0.822 0.411 APTT(s) 41.18±7.46 41.42±7.13 t=-0.214 0.829 PT(s) 15.90(14.70~17.90) 16.90(15.38~18.93) Z=-2.441 0.015 CEA(ng/mL) 2.98(1.79~4.73) 3.63(2.43~5.08) Z=-2.113 0.035 AFP(ng/mL) 9.33(4.77~18.86) 5.95(3.58~12.44) Z=-2.063 0.039 CA125(U/mL) 56.30(20.41~255.50) 160.13(31.77~324.55) Z=-2.270 0.023 CA19-9(U/mL) 25.28(11.00~41.38) 31.98(15.97~46.50) Z=-1.330 0.183 CA153(U/mL) 13.90(9.82~18.05) 15.37(11.33~20.91) Z=-1.601 0.109 PIVKA(mAU/mL) 23.40(18.00~36.00) 28.00(21.15~41.00) Z=-1.666 0.096 TT3(nmol/L) 1.76(1.42~2.06) 1.53(1.25~1.80) Z=-3.304 <0.001 TT4(nmol/L) 110.30(85.09~120.00) 92.70(76.85~111.52) Z=-2.221 0.026 TSH(μIU/mL) 2.41(1.75~3.60) 2.12(1.50~3.19) Z=-1.652 0.099 CD45+(个/μL) 1 032.06(756.63~1 297.77) 950.40(732.35~1 105.77) Z=-2.278 0.023 CD3+(个/μL) 767.60(523.15~967.34) 696.38(512.72~855.88) Z=-1.418 0.156 CD8+(个/μL) 218.05(150.78~353.83) 233.09(161.09~312.80) Z=-0.004 0.997 IL-1(pg/mL) 13.84(6.67~21.67) 12.19(5.15~19.66) Z=-1.366 0.172 IL-2(pg/mL) 3.24(2.69~4.58) 3.42(2.40~4.73) Z=-0.056 0.955 IL-4(pg/mL) 3.93±2.88 3.15±1.99 t=-1.949 0.055 IL-5(pg/mL) 2.84(2.03~3.67) 2.30(1.75~3.00) Z=-2.845 0.004 IFN-γ(pg/mL) 12.54(8.27~17.93) 10.75(6.63~17.13) Z=-1.098 0.272 IFN-α(pg/mL) 43.30(4.32~98.09) 18.71(4.10~90.87) Z=-1.580 0.114 TNF-α(pg/mL) 7.95(5.22~10.95) 6.43(4.36~9.08) Z=-2.176 0.030 表 3 再代偿组与对照组超声检查结果比较

Table 3. Comparison of ultrasound results between recompensation group and control group

指标 再代偿组(n=63) 对照组(n=154) 统计值 P值 门静脉宽度(mm) 12.00(10.00~13.20) 13.60(12.60~15.00) Z=-5.283 0.005 脾静脉宽度(mm) 9.00(6.00~10.00) 9.00(8.00~10.00) Z=-0.816 0.415 门静脉流速(cm/s) 14.21±3.36 13.73±2.76 t=-1.101 0.272 脾脏厚度(mm) 49.38±10.38 50.73±9.02 t=0.956 0.340 脾脏长度(mm) 138.80(124.00~153.00) 144.30(129.00~160.00) Z=-1.301 0.193 左肝长度(mm) 53.00(47.00~58.00) 54.00(50.00~58.55) Z=-1.362 0.173 右肝长度(mm) 109.00(96.00~119.00) 110.00(100.00~118.25) Z=0.051 0.959 表 4 多因素Logistic回归分析结果

Table 4. Results of multivariate Logistic regression analysis

项目 β值 SE Wald χ² OR 95%CI P值 HIV史 -1.634 0.737 4.918 0.195 0.046~0.827 0.027 少量腹水 1.221 0.509 5.746 3.390 1.249~9.199 0.017 部分脾栓塞史 1.120 0.569 3.867 3.064 1.004~9.350 0.049 AFP 0.003 0.001 8.182 1.003 1.001~1.006 0.004 门静脉宽度 -0.511 0.112 20.688 0.600 0.481~0.748 <0.001 注:HIV史赋值:是=1,否=0;部分脾脏栓塞史赋值:是=1,否=0;腹水赋值:中大量腹水=0,无腹水=1,少量腹水=2。

表 5 单个及联合预测因子的预测价值

Table 5. Predictive value of individual and combined predictors

项目 AUC 95%CI 敏感度 特异度 截断值 HIV史 0.556 0.475~0.637 0.175 0.937 腹水分级 0.641 0.560~0.723 0.630 0.651 部分脾栓塞史 0.560 0.472~0.647 0.929 0.190 AFP 0.589 0.503~0.676 0.556 0.649 8.79 门静脉宽度 0.745 0.671~0820 0.779 0.635 12.2 联合预测模型 0.817 0.751~0.882 0.841 0.701 -

[1] World Health Organization. Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. Accountability for the global health sector strategies 2016-2021: actions for impact[M]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. [2] COLLABORATORS POH. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: A modelling study[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 7( 5): 396- 415. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00472-6. [3] JALAN R, D’AMICO G, TREBICKA J, et al. New clinical and pathophysiological perspectives defining the trajectory of cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 75( Suppl 1): S14- S26. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.018. [4] YEO YH, HE XY, LV F, et al. Trends of cirrhosis-related mortality in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic[J]. J Clin Transl Hepatol, 2023, 11( 3): 751- 756. DOI: 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00313. [5] CRAIG AJ, von FELDEN J, GARCIA-LEZANA T, et al. Tumour evolution in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020, 17( 3): 139- 152. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-019-0229-4. [6] Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines on the management of ascites and complications in cirrhosis[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2017, 33( 10): 1847- 1863. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2017.10.003.中华医学会肝病学分会. 肝硬化腹水及相关并发症的诊疗指南[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2017, 33( 10): 1847- 1863. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2017.10.003. [7] de FRANCHIS R, BOSCH J, GARCIA-TSAO G, et al. Baveno VII-Renewing consensus in portal hypertension[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 76( 4): 959- 974. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.12.022. [8] Hepatology Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis(2023 version)[J]. Chin J Hepatol, 2023, 31( 8): 813- 826. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20230719-00011.中华医学会肝病学分会. 肝硬化腹水诊疗指南(2023年版)[J]. 中华肝脏病杂志, 2023, 31( 8): 813- 826. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20230719-00011. [9] KIM TH, UM SH, LEE YS, et al. Determinants of re-compensation in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis starting antiviral therapy[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2022, 55( 1): 83- 96. DOI: 10.1111/apt.16658. [10] JANG JW, CHOI JY, KIM YS, et al. Long-term effect of antiviral therapy on disease course after decompensation in patients with hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61( 6): 1809- 1820. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27723. [11] Chinese Society of Hepatology and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline for the prevention and treatment of hepatitis C(2022 version)[J]. Chin J Clin Infect Dis, 2022, 15( 6): 428- 447. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2022.06.002.中华医学会肝病学分会, 中华医学会感染病学分会. 丙型肝炎防治指南(2022年版)[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2022, 15( 6): 428- 447. DOl: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2022.06.002. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2022.06.002 [12] Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopology of Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines on the management of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2023, 9( 3): 527- 538. DOI: 10.3760/cmaj.cn501113-20220824-00436.中华医学会肝病学分会, 中华医学会消化病学分会, 中华医学会消化内镜学分会. 肝硬化门静脉高压食管胃静脉曲张出血的防治指南[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2023, 39( 3): 527- 538. DOI: 10.3760/cmaj.cn501113-20220824-00436. [13] General Office of National Health Commission. Standard for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer(2022 edition)[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2022, 38( 2): 288- 303. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.02.009.国家卫生健康委办公厅. 原发性肝癌诊疗指南(2022年版)[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2022, 38( 2): 288- 303. DOl: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.02.009. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.02.009 [14] WANG Q, ZHAO H, DENG Y, et al. Validation of Baveno VII criteria for recompensation in entecavir-treated patients with hepatitis B-related decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 77( 6): 1564- 1572. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.037. [15] ZHANG T, DENG Y, KANG HY, et al. Recompensation of complications in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis treated with entecavir antiviral therapy[J]. Chin J Hepatol, 2023, 31( 7): 692- 697. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20230324-00126.张婷, 邓优, 康海燕, 等. 恩替卡韦抗病毒治疗的乙型肝炎失代偿期肝硬化患者并发症的再代偿[J]. 中华肝脏病杂志, 2023, 31( 7): 692- 697. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20230324-00126. [16] HOFER BS, SIMBRUNNER B, HARTL L, et al. Hepatic recompensation according to Baveno VII criteria is linked to a significant survival benefit in decompensated alcohol-related cirrhosis[J]. Liver Int, 2023, 43( 10): 2220- 2231. DOI: 10.1111/liv.15676. [17] HOFER BS, BURGHART L, HALILBASIC E, et al. Evaluation of potential hepatic recompensation criteria in patients with PBC and decompensated cirrhosis[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2024, 59( 8): 962- 972. DOI: 10.1111/apt.17908. [18] BENMASSAOUD A, FREEMAN SC, ROCCARINA D, et al. Treatment for ascites in adults with decompensated liver cirrhosis: A network meta-analysis[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020, 1( 1): CD013123. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013123.pub2. [19] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69( 2): 406- 460. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [20] RIPOLL C, GROSZMANN R, GARCIA-TSAO G, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133( 2): 481- 488. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.024. [21] CARACENI P, RIGGIO O, ANGELI P, et al. Long-term albumin administration in decompensated cirrhosis(ANSWER): An open-label randomised trial[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391( 10138): 2417- 2429. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30840-7. [22] POSE E, TORRENTS A, REVERTER E, et al. A notable proportion of liver transplant candidates with alcohol-related cirrhosis can be delisted because of clinical improvement[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 75( 2): 275- 283. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.02.033. [23] ARAVINTHAN AD, BARBAS AS, DOYLE AC, et al. Characteristics of liver transplant candidates delisted following recompensation and predictors of such delisting in alcohol-related liver disease: A case-control study[J]. Transpl Int, 2017, 30( 11): 1140- 1149. DOI: 10.1111/tri.13008. [24] GIARD JM, DODGE JL, TERRAULT NA. Superior wait-list outcomes in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease compared with other indications for liver transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl, 2019, 25( 9): 1310- 1320. DOI: 10.1002/lt.25485. [25] JACHS M, HARTL L, SCHAUFLER D, et al. Amelioration of systemic inflammation in advanced chronic liver disease upon beta-blocker therapy translates into improved clinical outcomes[J]. Gut, 2021, 70( 9): 1758- 1767. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322712. [26] REIBERGER T, FERLITSCH A, PAYER BA, et al. Non-selective betablocker therapy decreases intestinal permeability and serum levels of LBP and IL-6 in patients with cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 58( 5): 911- 921. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.011. [27] GLUUD LL, KRAG A. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012( 8): CD004544. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004544.pub2. [28] HERNÁNDEZ-GEA V, ARACIL C, COLOMO A, et al. Development of ascites in compensated cirrhosis with severe portal hypertension treated with β-blockers[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107( 3): 418- 427. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2011.456. [29] D’AMICO G, MORABITO A, D’AMICO M, et al. New concepts on the clinical course and stratification of compensated and decompensated cirrhosis[J]. Hepatol Int, 2018, 12( Suppl 1): 34- 43. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-017-9808-z. [30] XIE QY, GAO FW, LEI ZH, et al. Comparative study of non-selective and highly selective splenic artery embolization in patients with liver cirrhosis secondary to hypersplenism[J]. Chin J Hepatobiliary Surgery, 2021, 27( 12): 917- 922. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113884-20210527-00182.谢青云, 高峰畏, 雷泽华, 等. 脾动脉非选择性与高选择性插管后部分脾栓塞术在肝硬化继发脾功能亢进患者中的对比研究[J]. 中华肝胆外科杂志, 2021, 27( 12): 917- 922. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113884-20210527-00182. [31] LI ZW, WANG YQ, ZHANG YW. The mechanism of action of partial splenic artery embolization in treatment of liver cirrhosis and hypersplenism[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2023, 39( 7): 1714- 1720. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.07.029.李宗伟, 汪桠琴, 张跃伟. 部分脾动脉栓塞治疗肝硬化脾功能亢进的作用机制[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2023, 39( 7): 1714- 1720. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.07.029. [32] MADOFF DC, DENYS A, WALLACE MJ, et al. Splenic arterial interventions: Anatomy, indications, technical considerations, and potential complications[J]. Radiographics, 2005, 25( Suppl 1): S191- S211. DOI: 10.1148/rg.25si055504. [33] BAI L, LI QG. Effect of partial splenic embolization on inflammatory response and coagulation in patients with hypersplenism in liver cirrhosis[J]. Clin Res, 2023, 31( 8): 36- 38. DOI: 10.12385/j.issn.2096-1278(2023)08-0036-03.白露, 李庆刚. 部分脾栓塞术对肝硬化脾功能亢进患者炎症反应及凝血功能的影响[J]. 临床研究, 2023, 31( 8): 36- 38. DOI: 10.12385/j.issn.2096-1278(2023)08-0036-03. [34] PAVEL V, SCHARF G, MESTER P, et al. Partial splenic embolization as a rescue and emergency treatment for portal hypertension and gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2023, 23( 1): 180. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-023-02808-1. [35] ISHIKAWA T, SASAKI R, NISHIMURA T, et al. A novel therapeutic strategy for esophageal varices using endoscopic treatment combined with splenic artery embolization according to the Child-Pugh classification[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14( 9): e0223153. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223153. [36] Committee on HIV/Liver Diseases, Chinese Association of STD and AIDS Prevention and Control; Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital, Guangzhou Medical University. Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of HIV co-infection with HBV and HCV[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2024, 40( 6): 1107- 1113. DOI: 10.12449/JCH240607.中国性病艾滋病防治协会HIV合并肝病专业委员会, 广州医科大学附属市八医院. 中国HIV合并HBV、HCV感染诊治专家共识[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2024, 40( 6): 1107- 1113. DOI: 10.12449/JCH240607. [37] van den EYNDE E, CRESPO M, ESTEBAN JI, et al. Response-guided therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in patients coinfected with HIV: A pilot trial[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2009, 48( 8): 1152- 1159. DOI: 10.1086/597470. [38] PINEDA JA, GARCÍA-GARCÍA JA, AGUILAR-GUISADO M, et al. Clinical progression of hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients undergoing highly active antiretroviral therapy[J]. Hepatology, 2007, 46( 3): 622- 630. DOI: 10.1002/hep.21757. [39] WEN J, ZHOU Y, WANG J, et al. Interactions between Th1 cells and Tregs affect regulation of hepatic fibrosis in biliary atresia through the IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2017, 24( 6): 997- 1006. DOI: 10.1038/cdd.2017.31. [40] DAGUR RS, WANG WM, CHENG Y, et al. Human hepatocyte depletion in the presence of HIV-1 infection in dual reconstituted humanized mice[J]. Biol Open, 2018, 7( 2): bio029785. DOI: 10.1242/bio.029785. [41] ARIFIN KT, SULAIMAN S, SAAD SM, et al. Elevation oftumour markers TGF-β,M2-PK, OV-6 and AFP in hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC)-induced rats and their suppression bymicroalgae Chlorella vulgaris[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17( 1): 879. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-017-3883-3. [42] MASETTI C, LIONETTI R, LUPO M, et al. Lack of reduction in serumalpha-fetoprotein during treatment with direct antiviral agents predicts hepatocellular carcinoma development in a large cohort of patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis[J]. J Viral Hepat, 2018, 25( 12): 1493- 1500. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.12982. [43] ZHAO P, ZHAI YF, ZHANG HH. Application of serum alpha fetoprotein and prothrombin time activity in predicting prognosis of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure[J]. J Prac Hepat, 2017, 20( 2): 230- 231. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5069.2017.02.027.赵萍, 翟玉峰, 张怀宏. 血清甲胎蛋白和凝血酶原活动度水平对慢加急性肝衰竭患者预后的预测价值研究[J]. 实用肝脏病杂志, 2017, 20( 2): 230- 231. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5069.2017.02.027. [44] ZHANG AM, YOU SL, WAN ZH, et al. Relation of liver fibrosis indicators and prognosis in hepatitis B-related acute on chronic liver failure[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2012, 28( 6): 459- 461. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2012.06.016.张爱民, 游绍莉, 万志红, 等. 乙型肝炎病毒相关慢加急性肝衰竭患者肝纤维化、肝功能、病毒学指标及甲胎蛋白水平与预后的关系[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2012, 28( 6): 459- 461. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2012.06.016. -

PDF下载 ( 1211 KB)

PDF下载 ( 1211 KB)

下载:

下载: