Mechanism of taurocholic acid in promoting the progression of liver cirrhosis

-

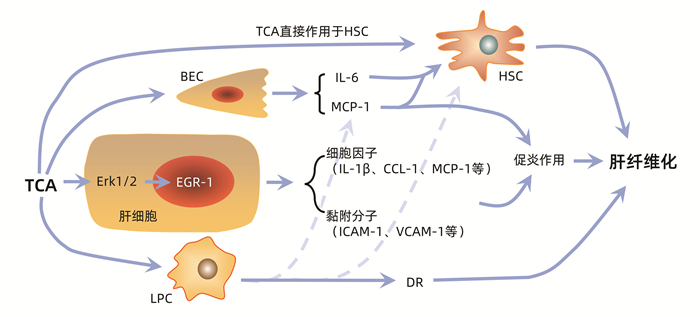

摘要: 胆汁酸是胆汁的主要成分,其外分泌入肠道帮助脂质和脂溶性维生素的吸收,也可作为信号分子调节胆汁酸代谢,帮助维持肠道稳态。而肝硬化过程中伴有不同程度的胆汁淤积,造成胆管损伤,肝脏细胞暴露于高水平胆汁酸会加速肝硬化进展从而形成恶性循环。在这些异常升高的胆汁酸中,以牛磺胆酸(TCA)水平升高最为显著,提示TCA在肝硬化过程中可能发挥重要作用。而目前对于TCA在肝硬化中的作用机制的研究相对较少,现有国内外相关研究表明,高水平TCA(≥50 μmol/L)可以通过作用于肝脏细胞(肝星状细胞、肝细胞、肝祖细胞、胆管上皮细胞)从而促进肝硬化进展。探讨了TCA促进肝硬化的详细机制,提示TCA具有作为肝硬化生物标志物与治疗靶点的临床潜力。Abstract: Bile acid is the main component of bile, and the external secretion of bile acid into the intestine can help with the absorption of lipids and fat-soluble vitamins; in addition, bile acid acts as a signal molecule to regulate bile acid metabolism and help maintain intestinal homeostasis. The process of liver cirrhosis is accompanied by varying degrees of cholestasis, causing bile duct injury, and exposure of liver cells to a high concentration of bile acid will accelerate the progression of liver cirrhosis and form a vicious circle. Among these abnormally elevated bile acids, taurocholic acid (TCA) shows the greatest increase, suggesting that TCA may play an important role in the process of liver cirrhosis. At present, there are relatively few studies on the mechanism of TCA in liver cirrhosis, and current studies in China and globally have shown that TCA at a high concentration (≥50 μmol/L) can promote the progression of liver cirrhosis by acting on liver cells (hepatic stellate cells, hepatocytes, hepatic progenitor cells, and bile duct epithelial cells). This article discusses the detailed mechanism of TCA in promoting liver cirrhosis and points out that TCA has the clinical potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target for liver cirrhosis.

-

Key words:

- Taurocholic Acid /

- Liver Cirrhosis /

- Cholestasis

-

非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)是一种常见的慢性肝病,包括非酒精性脂肪肝、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)及其相关肝纤维化和肝硬化[1],部分患者甚至进展为肝癌,现在被称为代谢相关脂肪性肝病(metabolic associated fatty liver disease,MAFLD)[2-3],随着肥胖发病率逐年增高和低龄化趋势,NAFLD成为儿童慢性肝病的常见原因[4],肝硬化的三大主要原因之一。目前MAFLD的发病机制仍不清楚,临床上亦缺乏有效的药物治疗,因此MAFLD发病机制的研究是当前的热点。

黏膜相关恒定T(mucosal associated invariant T,MAIT)淋巴细胞是一类新的天然免疫T淋巴细胞,是最丰富的TCRαβ+T淋巴细胞,以1类主要组织相容性复合体相关分子和不依赖MR1的方式快速激活MAIT淋巴细胞[5],发挥生物学功能,释放多种细胞因子,如IFNγ、TNFα、IL-17和溶细胞产物穿孔素及颗粒素分泌并脱颗粒(将CD107a暴露于细胞表面)等杀伤性细胞因子[6],迅速诱导细胞溶解和靶细胞的死亡。国外相关报道[7-9]显示MAIT淋巴细胞在成人MAFLD发病中起到减少肝脏炎症及促肝纤维化作用,但在儿童MAFLD发病中作用的研究甚少。本研究通过分析MAFLD儿童外周血MAIT淋巴细胞的变化及其与临床指标的相关性,探讨MAIT淋巴细胞在儿童MAFLD发生发展中的作用。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

收集2022年3月—2022年5月在本院肝病中心诊治的18例MAFLD患儿(MAFLD组)的外周血标本,根据年龄匹配的20例正常儿童作为对照(对照组),其外周血标本采集于本院健康管理中心。

1.2 纳入标准

MAFLD组纳入标准:脂肪肝合并超重/肥胖、2型糖尿病和代谢功能障碍中至少一项特征[1-2]。同时排除合并甲、乙、丙、丁、戊型肝炎病毒感染,自身免疫性肝病,人类免疫缺陷病毒等病毒感染。对照组纳入标准:肝功能正常,无慢性疾病,近期无感染史等。

1.3 方法

人外周血免疫细胞的制备:留取MAFLD组和对照组儿童外周血3 mL,将PBS加入3 mL新鲜全血中,吸取稀释后的外周血缓慢加到lymphoprep表面。全血在400×g室温下离心20 min,收集第二层外周血免疫细胞并转入含有PBS的离心管中,离心机800×g室温下离心10 min。离心结束后去上清,再加入10 mL PBS,离心机400×g室温下离心5 min,清洗外周血免疫细胞以彻底去除残留的lymphoprep。

应用流式细胞仪检测MAIT细胞,根据标准方案使用以下抗体:CD183(CXCR3)、CD279(PD-1), CD186(CXCR6)、CD3、TCRVα7.2、CD8、CD69、CD161、CD107a、CD196 (CCR6)、CD4和穿孔素抗体进行染色,上流式细胞仪(三激光八色流式细胞分析仪,型号:FacsCantoll,产地:美国)进行分析。外周血中MAIT细胞定义为CD3+CD161+TCRVα7.2+细胞。

收集MAFLD组和对照组儿童血常规及肝功能结果,使用瞬时弹性成像检测MAFLD组患儿的肝纤维化和脂肪含量,儿童MAFLD肝纤维化最佳临界值为6.65 kPa[10],区分有无脂肪变性的脂肪肝参数最佳临界值为222.5 dB/m[11]。

1.4 统计学方法

采用SPSS 23.0软件进行统计学分析。符合正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,两组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布的计量资料以M(P25~P75)表示,两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。MAFLD组患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞频率与肝损伤、肝脏脂肪含量和纤维化相关性分析应用Spearman相关分析法。P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 一般资料

MAFLD组18例患儿年龄波动在6.17~13.08岁,对照组20例儿童年龄波动在5.83~13.00岁。MAFLD组的中性粒细胞、ALT、AST水平高于对照组(P值均<0.05)(表 1)。MAFLD组患儿肝纤维化弹性值为5.55(4.18~7.13)kPa,脂肪肝参数为(253.85±16.40) dB/m。

表 1 两组患儿临床资料比较Table 1. The comparation of clinical data between the two groups指标 MAFLD组(n=18) 对照组(n=20) 统计值 P值 男/女(例) 10/8 11/9 年龄(岁) 10.65(8.44~11.87) 9.00(7.40~11.25) Z=-1.083 0.279 ALT(U/L) 37.30(25.08~157.53) 13.65(11.75~17.00) Z=-4.474 <0.001 AST(U/L) 29.95(26.08~62.70) 20.95(18.90~24.23) Z=-3.304 0.001 WBC(×109/L) 7.31±2.56 7.00±1.50 t=0.937 0.355 中性粒细胞(×109/L) 4.47(3.36~5.18) 3.62(2.77~3.97) Z=-2.222 0.026 淋巴细胞(×109/L) 2.76(2.38~3.11) 2.44(1.82~2.91) Z=-1.608 0.112 2.2 儿童外周血MAIT淋巴细胞频率比较

与对照组相比,MAFLD组患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞占CD3+T淋巴细胞的比例明显升高(P<0.001),CD4+CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞所占MAIT淋巴细胞比例明显升高,CD4-CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞所占MAIT淋巴细胞比例降低(P值均<0.001),CD4-CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞所占MAIT淋巴细胞比例无变化(P>0.05)(表 2)。

表 2 两组患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞及各亚组MAIT淋巴细胞频率比较Table 2. The comparation of the peripheral blood MAIT lymphocytes and subtypes between the two groups指标 MAFLD组(n=18) 对照组(n=20) Z值 P值 MAIT淋巴细胞(%) 2.98(1.83~5.99) 0.29(0.09~0.69) -4.765 <0.001 CD4+CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞(%) 13.75(3.28~30.33) 0.38(0~1.55) -3.703 <0.001 CD4-CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞(%) 26.45(1.03~47.03) 31.25(24.05~50.33) 0.254 >0.05 CD4-CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞(%) 9.20(1.16~16.80) 43.65(29.65~64.98) -3.876 <0.001 CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞(%) 25.65(14.78~84.95) 9.36(6.04~22.45) -2.675 <0.001 2.3 外周血MAIT淋巴细胞表型和功能的差异

与对照组相比,MAFLD组患儿外周血表达PD-1、CD69、CD107α、CXCR3、CXCR6和CCR6的MAIT淋巴细胞比例均明显升高(P值均<0.05)(表 3)。

表 3 两组患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞表型和功能的差异Table 3. Differences in phenotype and function of peripheral blood MAIT lymphocytes between the two groups指标 MAFLD组(n=18) 对照组(n=20) Z值 P值 PD-1(%) 21.80(8.38~51.70) 4.43(2.07~11.29) -3.334 0.001 CD69(%) 56.00(28.93~68.35) 18.90(13.23~31.18) -2.646 0.008 穿孔素(%) 9.32(4.53~18.80) 4.16(1.35~9.53) -1.827 0.068 CD107α(%) 45.20(26.03~59.03) 10.95(6.80~17.18) -3.172 0.002 CXCR3(%) 87.35(80.08~96.03) 44.80(32.93~53.00) -4.678 <0.001 CXCR6(%) 30.40(8.24~54.90) 6.02(3.27~21.58) -2.939 0.003 CCR6(%) 26.80(13.03~77.70) 4.94(3.32~17.13) -2.749 0.006 2.4 MAFLD组患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞频率与肝脏炎症、脂肪含量和纤维化程度的关系

CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞和CD107α阳性MAIT淋巴细胞比例与ALT呈负相关(P值均<0.05);MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4-CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞比例与ALT无相关性(P值均>0.05);MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4-CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞和CD107α阳性MAIT淋巴细胞比例与AST、瞬时弹性成像中脂肪肝参数以及弹性值均无相关性(P值均>0.05)(表 4)。

表 4 MAFLD组患儿外周血MAIT细胞频率与肝脏炎症、脂肪含量和纤维化程度相关性分析Table 4. Correlation analysis between the frequency of MAIT lymphocytes in peripheral blood and the degree of liver inflammation, fat content, and fibrosis in children with MAFLD项目 ALT AST 弹性值 脂肪肝参数 MAIT淋巴细胞 r值 0.041 -1.050 0.064 0.112 P值 0.871 0.677 0.801 0.660 CD4+CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞 r值 -0.305 -0.330 -0.303 -0.272 P值 0.218 0.181 0.221 0.275 CD4-CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞 r值 0.140 -0.130 -0.047 0.228 P值 0.580 0.606 0.854 0.363 CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞 r值 -0.474 -0.436 -0.347 -0.115 P值 0.047 0.071 0.158 0.650 CD107α阳性MAIT淋巴细胞 r值 -0.550 -0.334 -0.201 -0.168 P值 0.018 0.176 0.432 0.504 3. 讨论

MAIT细胞与代谢功能障碍的发展有关, 肥胖儿童外周血MAIT细胞频率高于非肥胖儿童[12],其频率随着肥胖人群年龄的增长而下降,糖尿病和肥胖成人外周血MAIT细胞频率降低[13-15],肥胖成人和儿童中的高IL-17+表型在胰岛素抵抗发展中发挥着重要作用[12, 16]。目前MAIT淋巴细胞在MAFLD发病中作用机制的研究主要集中在成人,研究发现,MAFLD患者中循环MAIT淋巴细胞频率降低[7-9, 17],伴随着CXCR6表达的增加,而肝脏中MAIT淋巴细胞数量则明显增加,与MAFLD活动评分呈正相关[8]。本研究发现,MAFLD患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞频率明显升高的同时伴有趋化因子CCR6、CXCR6、CXCR3表达的增加,表明MAFLD患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞亦具有更强的迁移至肝脏的倾向[8],MAFLD患者外周血MAIT淋巴细胞频率的变化亦有着随着年龄增长而有下降的趋势,而这种下降的趋势可能与其迁移至肝脏有关。MAIT淋巴细胞可分为DP(CD4+CD8+)MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8-(CD4+)MAIT淋巴细胞、CD4-CD8+(CD8+)MAIT淋巴细胞和CD4-CD8-(DN)MAIT淋巴细胞。本研究发现健康儿童中以CD4-CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞和CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞为主[18],而MAFLD组患儿中以CD4-CD8-MAIT淋巴细胞和CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞为主,且与对照组相比,MAFLD组患儿CD4+MAIT淋巴细胞和CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞所占MAIT细胞比率升高,CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞所占MAIT淋巴细胞比率降低。

MAIT淋巴细胞在MAFLD中的作用为保护还是促进作用,与其所处疾病阶段有关。MAFLD成人患者中,外周血MAIT淋巴细胞降低的同时伴随着功能的改变,高表达CD69、PD-1及IL-4的产生增加,而IFNγ和TNFα的产生减少等。在蛋氨酸胆碱缺乏诱导的NASH模型中,MAIT细胞在肝脏中富集,并通过产生IL-4和IL-10以及诱导抗炎M2巨噬细胞来保护肝脏炎症[8]。随着病情的进展,肝内MAIT淋巴细胞的频率下降,在肝硬化和肝细胞癌的进展中起到促进作用[7, 17, 19]。本研究发现,MAFLD患儿外周血MAIT淋巴细胞水平明显升高的同时,伴有CD69、PD-1及CD107表达的增加,提示MAIT淋巴细胞被激活并功能性耗竭的同时,伴随着细胞毒性能力的增加。进一步研究显示CD4+CD8+MAIT淋巴细胞、CD107阳性MAIT淋巴细胞比例与ALT水平呈负相关,说明MAFLD患儿外周血MAIT细胞在肝脏炎症中具有保护作用,与文献[8]报道一致。

综上所述,MAIT淋巴细胞比例在MAFLD患儿外周血中明显升高,并在肝脏炎症中起着保护作用。本研究的局限性在于样本量偏少,进展期肝纤维化患儿病例数少,未检测肝脏组织MAIT淋巴细胞数量和其功能改变,MAIT淋巴细胞在儿童MAFLD发病中确切的免疫学机制及作用尚待进一步明确。

-

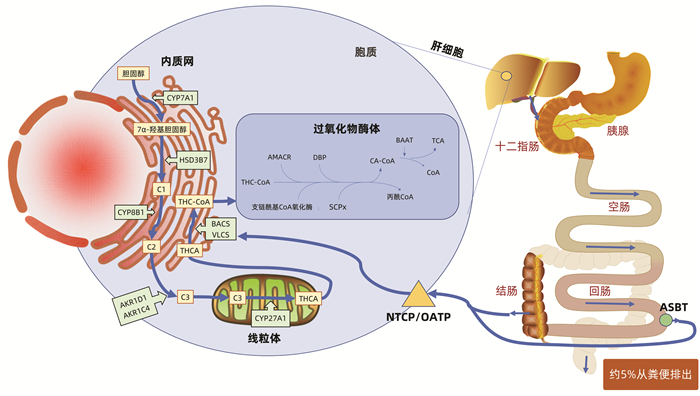

注:C1,7α-羟基-4-胆甾烯-3-酮;C2,7α,12α-羟基-4-胆甾烯-3-酮;C3,5β-胆甾烷-3α,7α,12α-三醇;CYP7A1,胆固醇7α-羟化酶;HSD3B7,3β-羟基-Δ5-C27-类固醇脱氢酶;CYP8B1,甾醇12α-羟化酶;AKR1D1,Δ4-3-氧类固醇-5β还原酶;AKR1C4,3α-羟基类固醇脱氢酶;CYP27A1,甾醇27-羟化酶;THCA,3α,7α,12α-三羟基胆甾酸;BACS,胆脂酰CoA合成酶;VLCS,超长链脂酰CoA合成酶;AMACR,α-甲基酰基辅酶A消旋酶;DBP,D-双功能蛋白;SCPx,甾醇载体蛋白x;BAAT,氨基酸N-酰基转移酶;ASBT,钠依赖回肠尖端胆汁转运体;NTCP,牛磺胆酸钠转运蛋白;OATP,有机阴离子转运蛋白。

图 1 TCA的合成示意图

-

[1] BARNETT R. Liver cirrhosis[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10144): 275. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31659-3. [2] PAROLA M, PINZANI M. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues[J]. Mol Aspects Med, 2019, 65: 37-55. DOI: 10.1016/j.mam.2018.09.002. [3] TROTTIER J, BIAŁEK A, CARON P, et al. Profiling circulating and urinary bile acids in patients with biliary obstruction before and after biliary stenting[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(7): e22094. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022094. [4] JIA W, WEI M, RAJANI C, et al. Targeting the alternative bile acid synthetic pathway for metabolic diseases[J]. Protein Cell, 2021, 12(5): 411-425. DOI: 10.1007/s13238-020-00804-9. [5] KIRIYAMA Y, NOCHI H. The biosynthesis, signaling, and neurological functions of bile acids[J]. Biomolecules, 2019, 9(6): 232. DOI: 10.3390/biom9060232. [6] TICHO AL, MALHOTRA P, DUDEJA PK, et al. Intestinal absorption of bile acids in health and disease[J]. Compr Physiol, 2019, 10(1): 21-56. DOI: 10.1002/cphy.c190007. [7] KOK B, ABRALDES JG. Child-Pugh classification: Time to abandon?[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2019, 39(1): 96-103. DOI: 10.1055/s-0038-1676805. [8] RIMINI M, ROVESTI G, CASADEI-GARDINI A. Child Pugh and ALBI grade: Past, present or future?[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2020, 8(17): 1044. DOI: 10.21037/atm-20-3709. [9] WANG X, XIE G, ZHAO A, et al. Serum bile acids are associated with pathological progression of hepatitis B-induced cirrhosis[J]. J Proteome Res, 2016, 15(4): 1126-1134. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00217. [10] LIU Z, ZHANG Z, HUANG M, et al. Taurocholic acid is an active promoting factor, not just a biomarker of progression of liver cirrhosis: Evidence from a human metabolomic study and in vitro experiments[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2018, 18(1): 112. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-018-0842-7. [11] HORVATITS T, DROLZ A, ROEDL K, et al. Serum bile acids as marker for acute decompensation and acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with non-cholestatic cirrhosis[J]. Liver Int, 2017, 37(2): 224-231. DOI: 10.1111/liv.13201. [12] KHOMICH O, IVANOV AV, BARTOSCH B. Metabolic hallmarks of hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis[J]. Cells, 2019, 9(1): 24. DOI: 10.3390/cells9010024. [13] MU M, ZUO S, WU RM, et al. Ferulic acid attenuates liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation via inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway[J]. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2018, 12: 4107-4115. DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S186726. [14] FAN Y, LI Y, CHU Y, et al. Toll-like receptors recognize intestinal microbes in liver cirrhosis[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 608498. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.608498. [15] SEKI E, de MINICIS S, OSTERREICHER CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis[J]. Nat Med, 2007, 13(11): 1324-1332. DOI: 10.1038/nm1663. [16] FABREGAT I, CABALLERO-DíAZ D. Transforming growth factor-β-induced cell plasticity in liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis[J]. Front Oncol, 2018, 8: 357. [17] CAJA L, DITURI F, MANCARELLA S, et al. TGF-β and the tissue microenvironment: Relevance in fibrosis and cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(5): 1294. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19051294. [18] GHAFOORY S, VARSHNEY R, ROBISON T, et al. Platelet TGF-β1 deficiency decreases liver fibrosis in a mouse model of liver injury[J]. Blood Adv, 2018, 2(5): 470-480. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010868. [19] PAIK YH, SCHWABE RF, BATALLER R, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells[J]. Hepatology, 2003, 37(5): 1043-1055. DOI: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [20] WEI S, MA X, ZHAO Y. Mechanism of hydrophobic bile acid-induced hepatocyte injury and drug discovery[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2020, 11: 1084. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01084. [21] ALLEN K, JAESCHKE H, COPPLE BL. Bile acids induce inflammatory genes in hepatocytes: A novel mechanism of inflammation during obstructive cholestasis[J]. Am J Pathol, 2011, 178(1): 175-186. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.026. [22] ALLEN K, KIM ND, MOON JO, et al. Upregulation of early growth response factor-1 by bile acids requires mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2010, 243(1): 63-67. DOI: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.013. [23] GUJRAL JS, LIU J, FARHOOD A, et al. Functional importance of ICAM-1 in the mechanism of neutrophil-induced liver injury in bile duct-ligated mice[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2004, 286(3): G499-507. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2003. [24] CAI X, LI Z, ZHANG Q, et al. CXCL6-EGFR-induced Kupffer cells secrete TGF-β1 promoting hepatic stellate cell activation via the SMAD2/BRD4/C-MYC/EZH2 pathway in liver fibrosis[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2018, 22(10): 5050-5061. DOI: 10.1111/jcmm.13787. [25] KIM ND, MOON JO, SLITT AL, et al. Early growth response factor-1 is critical for cholestatic liver injury[J]. Toxicol Sci, 2006, 90(2): 586-595. DOI: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj111. [26] MARRA F, ROMANELLI RG, GIANNINI C, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 as a chemoattractant for human hepatic stellate cells[J]. Hepatology, 1999, 29(1): 140-148. DOI: 10.1002/hep.510290107. [27] QUECK A, BODE H, USCHNER FE, et al. Systemic MCP-1 levels derive mainly from injured liver and are associated with complications in cirrhosis[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 354. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00354. [28] RAMM GA, SHEPHERD RW, HOSKINS AC, et al. Fibrogenesis in pediatric cholestatic liver disease: Role of taurocholate and hepatocyte-derived monocyte chemotaxis protein-1 in hepatic stellate cell recruitment[J]. Hepatology, 2009, 49(2): 533-544. DOI: 10.1002/hep.22637. [29] LI L, WEI W, LI Z, et al. The spleen promotes the secretion of CCL2 and supports an M1 dominant phenotype in hepatic macrophages during liver fibrosis[J]. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2018, 51(2): 557-574. DOI: 10.1159/000495276. [30] SUN T, ANNUNZIATO S, TCHORZ JS. Hepatic ductular reaction: A double-edged sword[J]. Aging (Albany NY), 2019, 11(21): 9223-9224. DOI: 10.18632/aging.102386. [31] SATO K, MARZIONI M, MENG F, et al. Ductular reaction in liver diseases: pathological mechanisms and translational significances[J]. Hepatology, 2019, 69(1): 420-430. DOI: 10.1002/hep.30150. [32] POZNIAK KN, PEAREN MA, PEREIRA TN, et al. Taurocholate induces biliary differentiation of liver progenitor cells causing hepatic stellate cell chemotaxis in the ductular reaction: Role in pediatric cystic fibrosis liver disease[J]. Am J Pathol, 2017, 187(12): 2744-2757. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.08.024. [33] RUDDELL RG, KNIGHT B, TIRNITZ-PARKER JE, et al. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor signaling regulates hepatic stellate cell function and wound healing in a murine model of chronic liver injury[J]. Hepatology, 2009, 49(1): 227-239. DOI: 10.1002/hep.22597. [34] TIRNITZ-PARKER JE, OLYNYK JK, RAMM GA. Role of TWEAK in coregulating liver progenitor cell and fibrogenic responses[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 59(3): 1198-1201. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26701. [35] LAMIREAU T, ZOLTOWSKA M, LEVY E, et al. Effects of bile acids on biliary epithelial cells: Proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine secretion[J]. Life Sci, 2003, 72(12): 1401-1411. DOI: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02408-6. [36] XIANG DM, SUN W, NING BF, et al. The HLF/IL-6/STAT3 feedforward circuit drives hepatic stellate cell activation to promote liver fibrosis[J]. Gut, 2018, 67(9): 1704-1715. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313392. [37] REMMLER J, SCHNEIDER C, TREUNER-KAUEROFF T, et al. Increased level of interleukin 6 associates with increased 90-day and 1-year mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 16(5): 730-737. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.017. [38] LABENZ C, TOENGES G, HUBER Y, et al. Raised serum Interleukin-6 identifies patients with liver cirrhosis at high risk for overt hepatic encephalopathy[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2019, 50(10): 1112-1119. DOI: 10.1111/apt.15515. [39] DU PLESSIS J, VANHEEL H, JANSSEN CE, et al. Activated intestinal macrophages in patients with cirrhosis release NO and IL-6 that may disrupt intestinal barrier function[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 58(6): 1125-1132. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.038. [40] MANCINELLI R, ONORI P, GAUDIO E, et al. Taurocholate feeding to bile duct ligated rats prevents caffeic acid-induced bile duct damage by changes in cholangiocyte VEGF expression[J]. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2009, 234(4): 462-474. DOI: 10.3181/0808-RM-255. [41] GAUDIO E, BARBARO B, ALVARO D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates rat cholangiocyte proliferation via an autocrine mechanism[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130(4): 1270-1282. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.034. -

PDF下载 ( 3064 KB)

PDF下载 ( 3064 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: