经肝动脉化疗栓塞术联合抗血管生成药基础上使用程序性死亡受体1抑制剂治疗中晚期肝细胞癌的有效性和安全性分析

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.05.021

Efficacy and safety of programmed death-1 inhibitor combined with transarterial chemoembolization and anti-angiogenic drugs in treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

-

摘要:

目的 探讨经肝动脉化疗栓塞术(TACE)联合抗血管生成药(TKI)的基础上后续使用程序性死亡受体1(PD-1)抑制剂与TACE+TKI两种方式治疗中晚期肝细胞癌(HCC)的有效性、安全性和预后影响因素。 方法 选取2018年6月—2021年7月在空军军医大学第一附属医院所有接受TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂和部分接受TACE+TKI治疗的患者。收集患者的临床资料,采用倾向性评分匹配法平衡组间基线特征。计数资料2组间比较采用χ2检验,TACE次数2组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验,Kaplan-Meier法分析患者的总生存期,单因素和多因素Cox回归模型分析相关预后影响因素。 结果 共筛选到181例中晚期HCC患者,其中TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂治疗的患者为50例,倾向性评分匹配后,纳入40例TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂治疗患者(观察组)和40例TACE+TKI治疗患者(对照组)。至随访截止时间,中位随访时间为28.6个月(95%CI:22.1~35.1),观察组的中位生存期为15.9个月(95%CI:7.5~24.2),对照组中位生存期为11.2个月(95%CI:5.0~17.5)。Cox回归分析提示PD-1抑制剂的应用(HR=0.42,95%CI:0.23~0.80,P=0.008)、TACE次数(HR=0.67,95%CI:0.46~0.99,P=0.043)、Child-Pugh分级(HR=2.40,95%CI:1.15~5.00,P=0.019)和血管侵犯(HR=3.42,95%CI:1.11~9.42,P=0.031)是患者预后的独立影响因素。观察组与对照组的2级以上不良反应发生率均为40%,未见显著性差异(P=0.818)。 结论 TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂较TACE+TKI治疗中晚期HCC患者可以明显延长患者生存期,且不良反应相对可控。 -

关键词:

- 癌, 肝细胞 /

- 化学栓塞, 治疗性 /

- 程序性细胞死亡受体1 /

- 治疗结果

Abstract:Objective To investigate the efficacy and safety of programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) inhibitor combined with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and anti-angiogenic drug tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) versus TACE combined with TKI in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and related influencing factors for prognosis. Methods An analysis was performed for all patients who received TACE+TKI+PD-1 inhibitor and some patients who received TACE+TKI in The First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University from June 2018 to July 2021. Related clinical data were collected, and propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance the baseline characteristics between groups. The chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between two groups; the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparison of the number of TACE procedures between two groups; the Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze overall survival (OS), and univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to analyze the influencing factors for prognosis. Results A total of 181 patients with advanced HCC were screened out, among whom 50 patients were treated with TACE+TKI+PD-1 inhibitor; after PSM, 40 patients treated with TACE+TKI+PD-1 inhibitor were enrolled as observation group and 40 patients treated with TACE+TKI were enrolled as control group. At the end of follow-up, the median follow-up time was 28.6 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 22.1-35.1) months, and the median OS was 15.9 (95%CI: 7.5-24.2) months in the observation group and 11.2 (95%CI: 5.0-17.5) months in the control group. The Cox regression analysis showed that the application of PD-1 inhibitor (hazard ratio [HR]=0.42, 95%CI: 0.23-0.80, P=0.008), the number of TACE procedures (HR=0.67, 95%CI: 0.46-0.99, P=0.043), Child-Pugh class (HR=2.40, 95%CI: 1.15-5.00, P=0.019), and vascular invasion (HR=3.42, 95%CI: 1.11-9.42, P=0.031) were independent influencing factors for prognosis. The incidence rate of grade > 2 adverse events was 40% for both the observation group and the control group, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (P=0.818). Conclusion Compared with TACE+TKI, TACE+TKI+PD-1 inhibitor can significantly prolong the OS of patients in advanced HCC, with relatively controllable adverse events. -

在世界范围内,肝细胞癌(HCC)是第六大常见肿瘤,也是导致肿瘤相关死亡的第四大原因[1]。针对肝癌的有效治疗是我国医疗卫生领域沉重的负担之一[2]。据统计,将近70%的肝癌患者在确诊时已处于中晚期[3-4],不适合进行外科手术,只能行姑息治疗,包括经肝动脉化疗栓塞术(TACE)、分子靶向治疗和免疫治疗等[5]。

TACE是巴塞罗那分期(BCLC) B期肝癌的标准治疗方式[6-7]。与营养支持治疗相比,TACE能够明显延长BCLC B期患者的生存时间[8-9];且对于肝功能、体能良好的C期患者,TACE疗效不差于标准的靶向治疗[10]。此外,TACE能够使部分不可切除的中晚期患者降期转化为可手术切除[11]。然而,中期肝癌存在很大的异质性,特别是肿瘤负荷的异质性。在肝功能和体能良好的情况下,肿瘤负荷越重,对TACE治疗反应越差,TACE术后复发率也越高[12]。基于TACE的不足,近年来TACE联合系统性治疗的临床研究越来越多,并显示出良好的效果。TACE联合系统性治疗主要分为两个方面:一是TACE联合抗血管生成的靶向药物,包括索拉非尼(sorafenib)、仑伐替尼(lenvatinib)、瑞戈非尼(regorafenib)和阿帕替尼(apatinib)等酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKI)。这类药物可以抑制血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)1~3受体以及血小板衍生生长因子受体β等肿瘤血管生成因子的靶点,抑制肿瘤微环境中血管的形成,能够对抗TACE术后VEGF的升高,在理论上两者存在协同作用[4]。相关临床研究[13]也证实TACE联合索拉非尼比单纯TACE更能改善中晚期患者的预后。二是TACE联合免疫检查点抑制剂的免疫治疗,包括程序性死亡受体1及其配体(PD-1/PD-L1)抑制剂和细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关抗原4抑制剂等。这类药物可以增强肿瘤微环境的免疫反应[14],特别是PD-1抑制剂,能够对抗TACE术后残存肿瘤细胞高表达的PD-L1而引起的免疫抑制效应,从理论上二者有协同作用[15]。但目前TACE联合免疫治疗尚缺乏循证医学证据的支持。

TACE、TKI和免疫治疗是目前中晚期肝癌的3种主要治疗手段,其抗肿瘤的机制不同。从理论上推测,三者联合既可以起到协同抗瘤的效果,又能相互克服各自的不足,进而起到减毒增效的作用。但三者联合治疗尚缺乏临床安全性和有效性的报道。本研究旨在探索该联合治疗方法的安全性和有效性。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

纳入2018年6月—2021年7月于本院接受TACE+TKI和PD-1抑制剂治疗的中晚期HCC患者作为观察组,并且纳入部分仅使用TACE+TKI的患者作为对照组。纳入标准:(1)临床或病理明确诊断为HCC;(2)根据改良版实体瘤疗效评价标准(mRECIST),至少有一个靶病灶(长径≥10 mm);(3)在本院至少行1次TACE治疗+TKI和PD-1抑制剂治疗。排除标准:(1)合并第二种恶性肿瘤;(2)临床资料不全;(3)失访。

1.2 研究方法

1.2.1 TACE

所有患者的TACE治疗均使用D-TACE,即根据肿瘤大小、数目及患者全身情况,使用药物性洗脱微球(drug-eluting beads,DEB)加载化疗药,包括:阿霉素(10~50 mg)、顺铂(10~110 mg)、表柔比星(10~50 mg)或奥沙利铂(100~200 mg),适量造影剂混匀后经导管脉冲式注射进行肿瘤栓塞,见肿瘤供血动脉血流缓慢,导管退至肝总动脉,再次行高压造影见靶病灶染色消失。每次TACE治疗后4~6周进行1次CT扫描。对于治疗后复发的患者,再次TACE治疗前已确认存活肿瘤或局部或远处肝内复发的存在。

1.2.2 TKI

患者TACE术前或术后3~7 d开始口服TKI。索拉非尼起始剂量为400 mg,口服,2次/d。仑伐替尼:体质量≥60 kg者,12 mg,口服,1次/d;体质量<60 kg者,8 mg,口服,1次/d。依据不良反应情况,实行逐级减量原则,调整服药剂量。如仍不能耐受,则需停止服用,换用二线治疗药物。

1.2.3 PD-1抑制剂

卡瑞丽珠单抗200 mg,每3周1次;信迪利单抗200 mg,每3周1次;帕博利珠单抗2 mg/kg,每3周1次。对于副反应不可耐受或者使用后仍进展的患者,则停止使用。

1.3 观察指标

回顾性收集患者临床特征和预后相关数据。临床特征包括年龄、性别、肝癌病因、ECOG评分、是否达到Up-to-7标准[即肿瘤个数加肿瘤最大径(cm)是否超过7]等。预后相关数据包括不良反应和生存状况。不良反应以常见不良事件5.0版(CTCAE V5.0)进行评价,TACE术后主要观察栓塞后综合征,并记录TKI和PD-1抑制剂治疗后的不良反应。

1.4 统计学方法

由于肝癌较大异质性,采用倾向性评分匹配(PSM)法(1∶ 1配对)来减少2组的基线差异。由于不同患者TACE+TKI后起始接受PD-1抑制剂时间不同,为了避免永久性时间误差[16],使2组患者的总生存期具有可比性,在观察组(TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂)中,将PD-1抑制剂开始应用至患者死亡或随访截止(2021年8月28日)定义为观察组的总生存期;在对照组(TACE+TKI)中,患者的总生存时间(第1次TACE至患者死亡或随访截止时间)减去观察组中与之配对患者的PD-1抑制剂使用的时间间隔(第1次TACE至PD-1抑制剂第1次使用时间间隔)定义为对照组的总生存期。排除对照组中总生存期<0及观察组中与之配对的患者。

采用SPSS 26.0进行统计学处理。计数资料2组间比较采用χ2检验。TACE次数2组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。生存分析采用Kaplan-Meier法,2组间生存情况比较采用log-rank检验。预后影响因素采用单因素和多因素Cox回归分析。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 基本特征

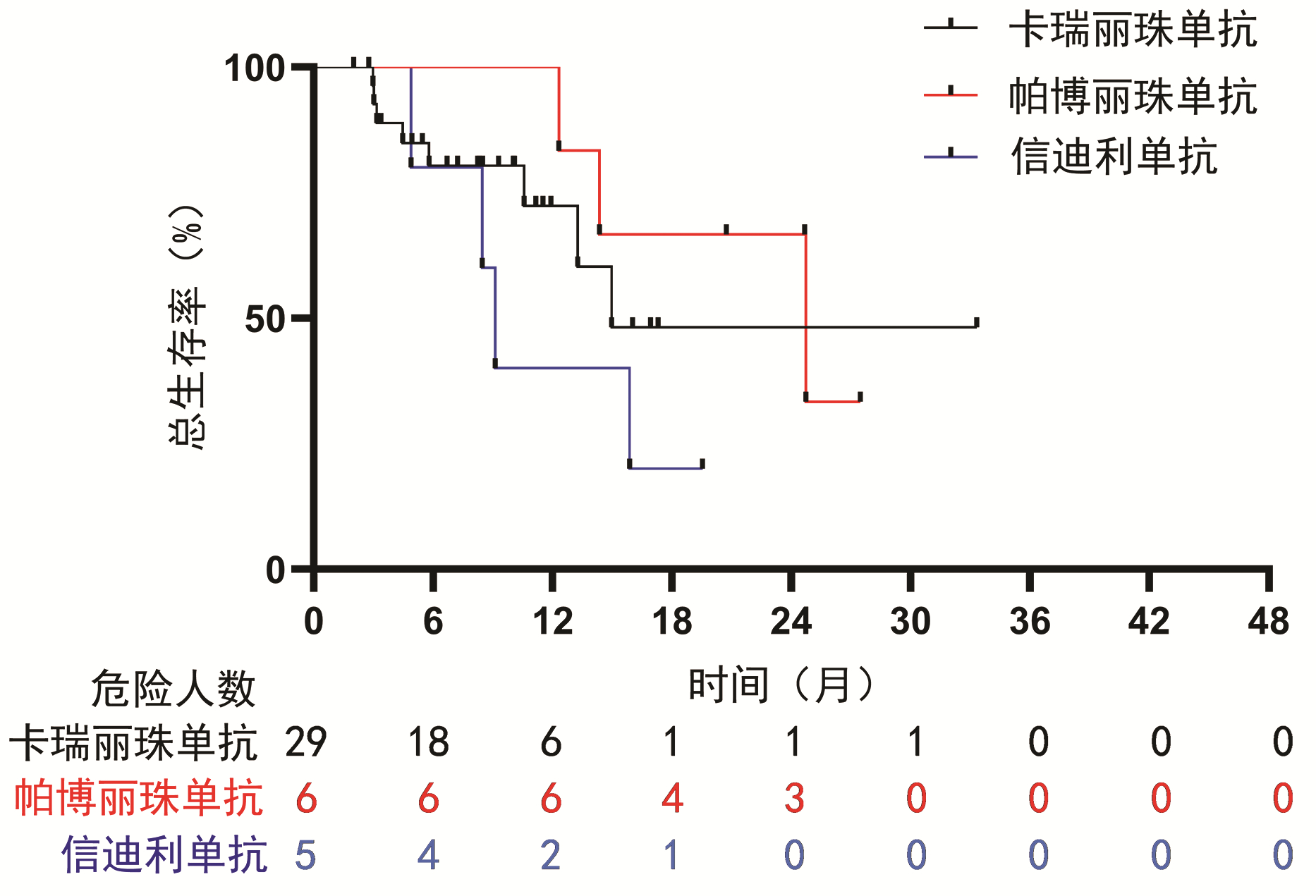

共筛选181例HCC患者,排除15例不符合纳入排除标准患者,6例临床资料不全患者,21例失访患者,139例患者纳入本研究,其中对照组89例,观察组50例。PSM后,共80例患者进行最后的统计学分析。在匹配前,随访期间接受的TACE次数在两组间不均衡,匹配后,两组基线均衡(表 1)。中位随访时间为28.6个月(95%CI:22.1~35.1)。PD-1抑制剂治疗包括:卡瑞丽珠单抗29例,信迪利单抗6例,帕博丽珠单抗5例,PD-1抑制剂使用次数中位数为6次(4.0~13.8),其中一线治疗7例,二线治疗20例,三线治疗13例。

表 1 患者基线资料Table 1. Baseline characteristics for the study patients临床特征 PSM (1∶1匹配)前 PSM(1∶1匹配)后 总计

(n=139)对照组

(n=89)观察组

(n=50)P值 总计

(n=80)对照组

(n=40)观察组

(n=40)P值 男[例(%)] 112(80.6) 72(80.9) 40(80.0) 0.898 63(78.8) 31(77.5) 32(80.0) >0.05 年龄>60岁[例(%)] 46(33.1) 29(32.6) 17(34.0) 0.865 26(32.5) 13(32.5) 13(32.5) 1.000 病因[例(%)] 0.268 0.465 乙型肝炎 119(85.6) 78(87.6) 41(82.0) 69(86.2) 36(90.0) 33(82.5) 丙型肝炎 5(3.6) 4(4.5) 1(2.0) 1(1.2) 0 1(2.5) 其他 15(10.8) 7(7.9) 8(16.0) 10(12.5) 4(10.0) 6(15.0) 靶向药物类型[例(%)] 0.971 >0.05 索拉非尼或仑伐替尼 104(74.8) 66(74.2) 38(76.0) 59(73.8) 30(75.0) 29(72.5) 阿帕替尼或瑞戈非尼 35(25.2) 23(25.8) 12(24.0) 21(26.2) 10(25.0) 11(27.5) Child-Pugh评分[例(%)] 0.898 0.780 A级 112(80.6) 72(80.9) 40(80.0) 64(80.0) 31(77.5) 33(82.5) B级 27(19.4) 17(19.1) 10(20.0) 16(20.0) 9(22.5) 7(17.5) ECOG评分[例(%)] 0.949 0.789 0分 108(77.7) 69(77.5) 39(78.0) 62(77.5) 32(80.0) 30(75.0) 1分 31(22.3) 20(22.5) 11(22.0) 18(22.5) 8(20.0) 10(25.0) BCLC分期[例(%)] 0.961 >0.05 B期 58(41.7) 37(41.6) 21(42.0) 31(38.7) 15(37.5) 16(40.0) C期 81(58.3) 52(58.4) 29(58.0) 49(61.3) 25(62.5) 24(60.0) AFP[例(%)] 0.856 0.819 ≤400 ng/mL 57(41.0) 37(41.6) 20(40.0) 32(40.0) 15(37.5) 17(42.5) >400 ng/mL 82(59.0) 52(58.4) 30(60.0) 48(60.0) 25(62.5) 23(57.5) 腹水[例(%)] 0.767 >0.05 无 115(82.7) 73(82.0) 42(84.0) 65(81.2) 32(80.0) 33(82.5) 少量 24(17.3) 16(18.0) 8(16.0) 15(18.8) 8(20.0) 7(17.5) 肝外转移[例(%)] 0.236 0.823 无 76(54.7) 52(58.4) 24(48.0) 38(47.5) 20(50.0) 18(45.0) 有 63(45.3) 37(41.6) 26(52.0) 42(52.5) 20(50.0) 22(55.0) 血管侵犯[例(%)] 0.683 0.817 无 92(66.2) 60(67.4) 32(64.0) 50(62.5) 24(60.0) 26(65.0) 有 47(33.8) 29(32.6) 18(36.0) 30(37.5) 16(40.0) 14(35.0) Up-to-7标准[例(%)] 0.208 0.482 未超出 57(41.0) 40(44.9) 17(34.0) 28(35.0) 16(40.0) 12(30.0) 超出 82(59.0) 49(55.1) 33(66.0) 52(65.0) 24(60.0) 28(70.0) TACE次数 0.038 0.765 1次 78 55 23 42 20 22 2次 33 21 12 19 10 9 3次 14 6 8 11 7 4 ≥4次 14 7 7 8 3 5 2.2 生存情况

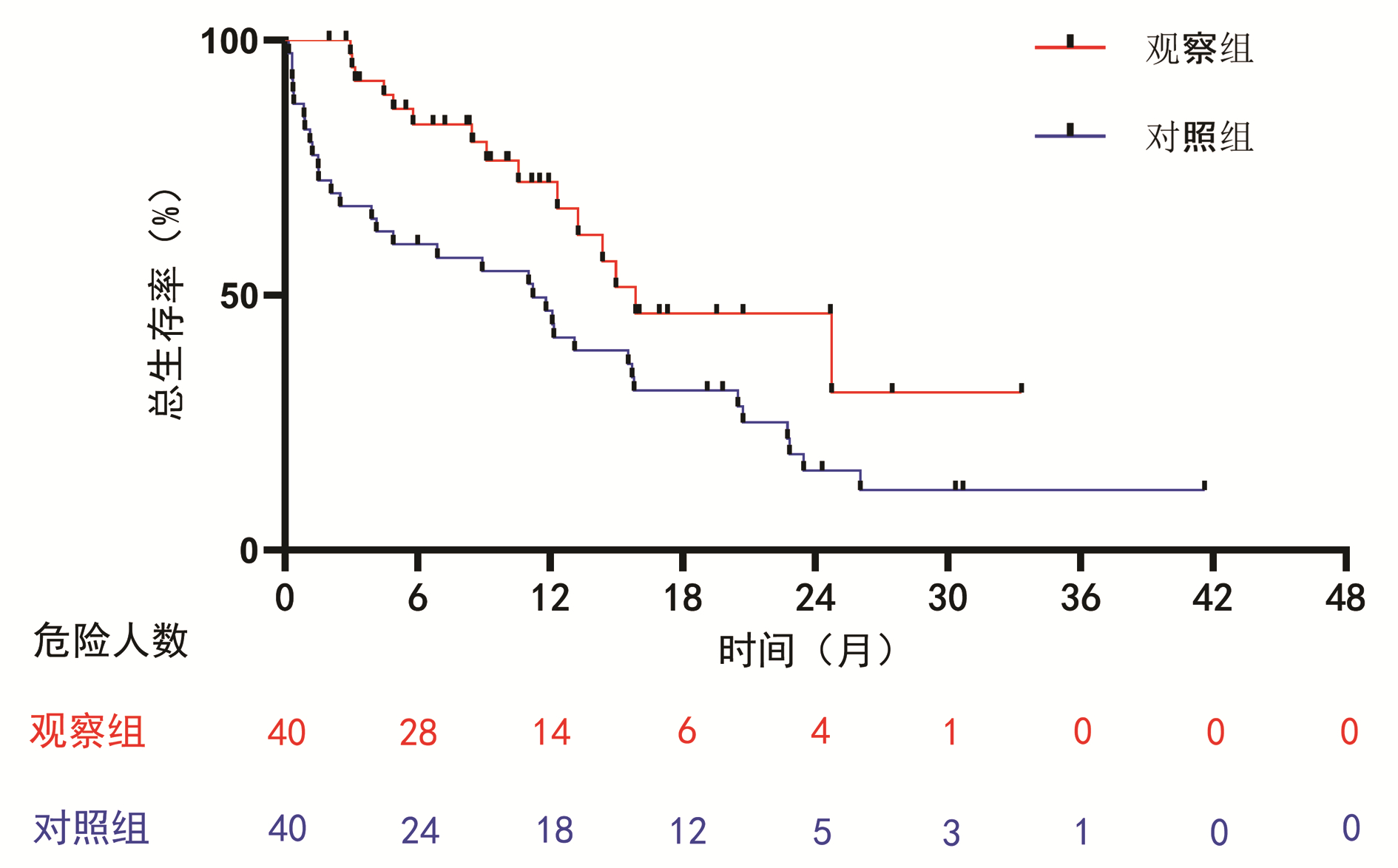

至随访截止时间,观察组中位生存期为15.9个月(95%CI:7.5~24.2),对照组中位生存期为11.2个月(95%CI:5.0~17.5)。观察组较对照组显著延长了患者的总生存时间(HR=0.42,95%CI:0.23~0.80,P=0.008)(图 1)。

2.3 单因素与多因素分析

单因素分析显示,PD-1抑制剂的应用、Child-Pugh分级、BCLC分期、肝外转移、血管侵犯和TACE次数是患者生存的影响因素(P值均<0.05),但索拉非尼和仑伐替尼对比瑞戈非尼和阿帕替尼并没有明显的优势(P=0.636)。将P<0.05的变量纳入多因素分析,结果显示PD-1抑制剂的应用(HR=0.42,P=0.008)、TACE次数(HR=0.67,P=0.043)、Child-Pugh分级(HR=2.40,P=0.019)和血管侵犯(HR=3.42,P=0.031)是患者预后的独立影响因素(表 2)。

表 2 单因素与多因素分析预后影响因素Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis to explore prognostic factors临床特征 单因素分析 多因素分析 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 应用PD-1抑制剂(ref: 未应用) 0.47(0.26~0.87) 0.017 0.42(0.23~0.80) 0.008 男(ref: 女) 1.21(0.59~2.50) 0.602 年龄>60岁(ref: ≤60岁) 1.27(0.69~2.32) 0.441 病因 乙型肝炎(ref: 其他) 3 007.25(0~2.64×1087) 0.935 丙型肝炎(ref: 其他) 3 060.73(0~2.68×1087) 0.935 索拉非尼和仑伐替尼(ref: 阿帕替尼和瑞戈非尼) 0.84(0.43~1.67) 0.636 Child-Pugh C级(ref: B级) 2.42(1.36~4.70) 0.008 2.40(1.15~5.00) 0.019 ECOG 1分(ref: 0分) 1.41(0.71~2.78) 0.323 BCLC C期(ref: B期) 2.07(1.09~3.91) 0.026 0.85(0.29~2.53) 0.769 AFP>400 ng/mL(ref: ≤400) 1.02(0.57~1.83) 0.952 腹水(ref: 无) 1.88(0.95~3.72) 0.069 肝外转移(ref: 无) 1.82(1.01~3.27) 0.045 0.73(0.21~2.53) 0.617 血管侵犯(ref: 无) 2.30(1.30~4.07) 0.004 3.24(1.11~9.42) 0.031 超过Up-to-7标准(ref: 否) 1.31(0.73~2.38) 0.368 TACE次数每增加1次 0.64(0.46~0.87) 0.005 0.67(0.46~0.99) 0.043 2.4 亚组分析

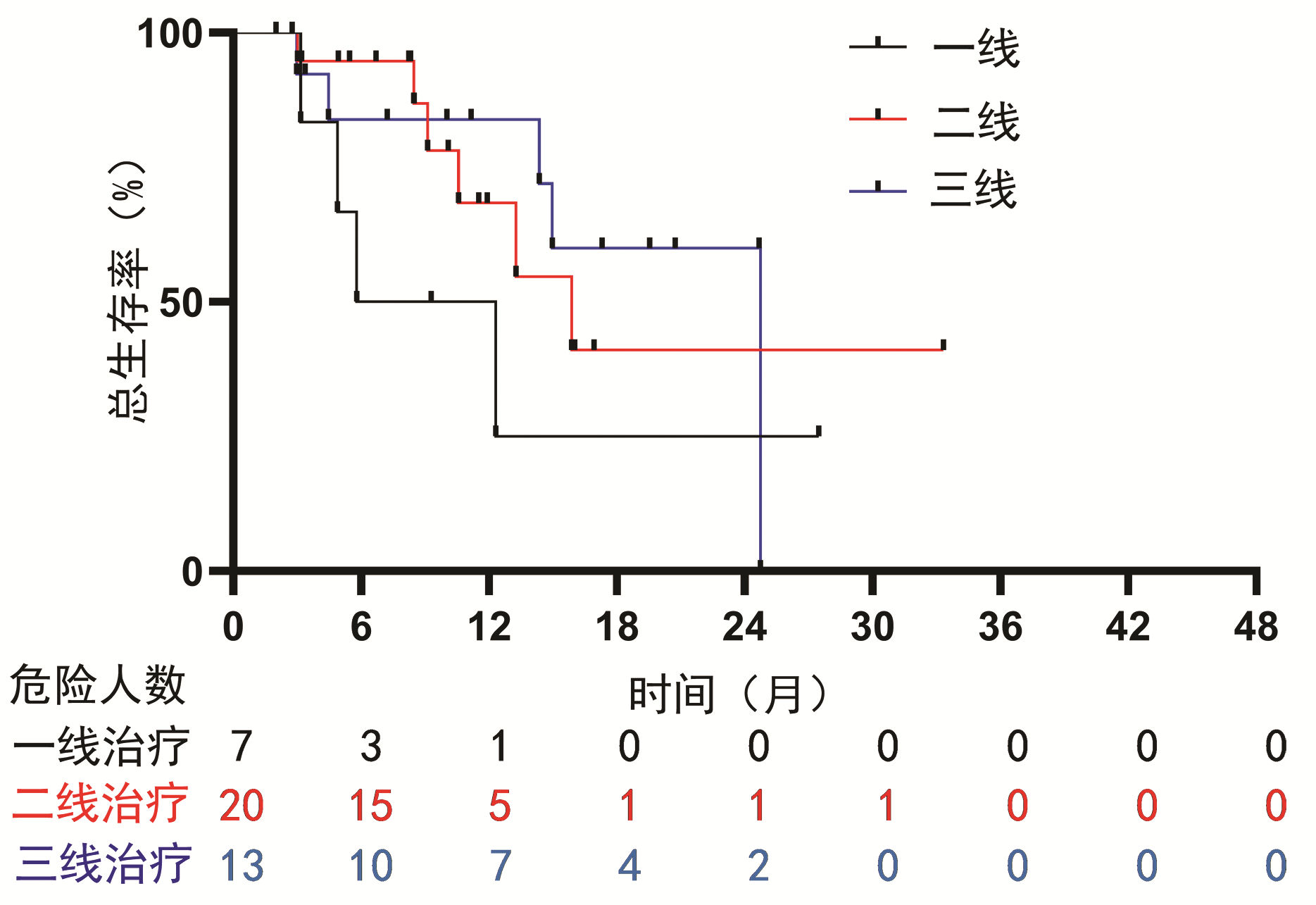

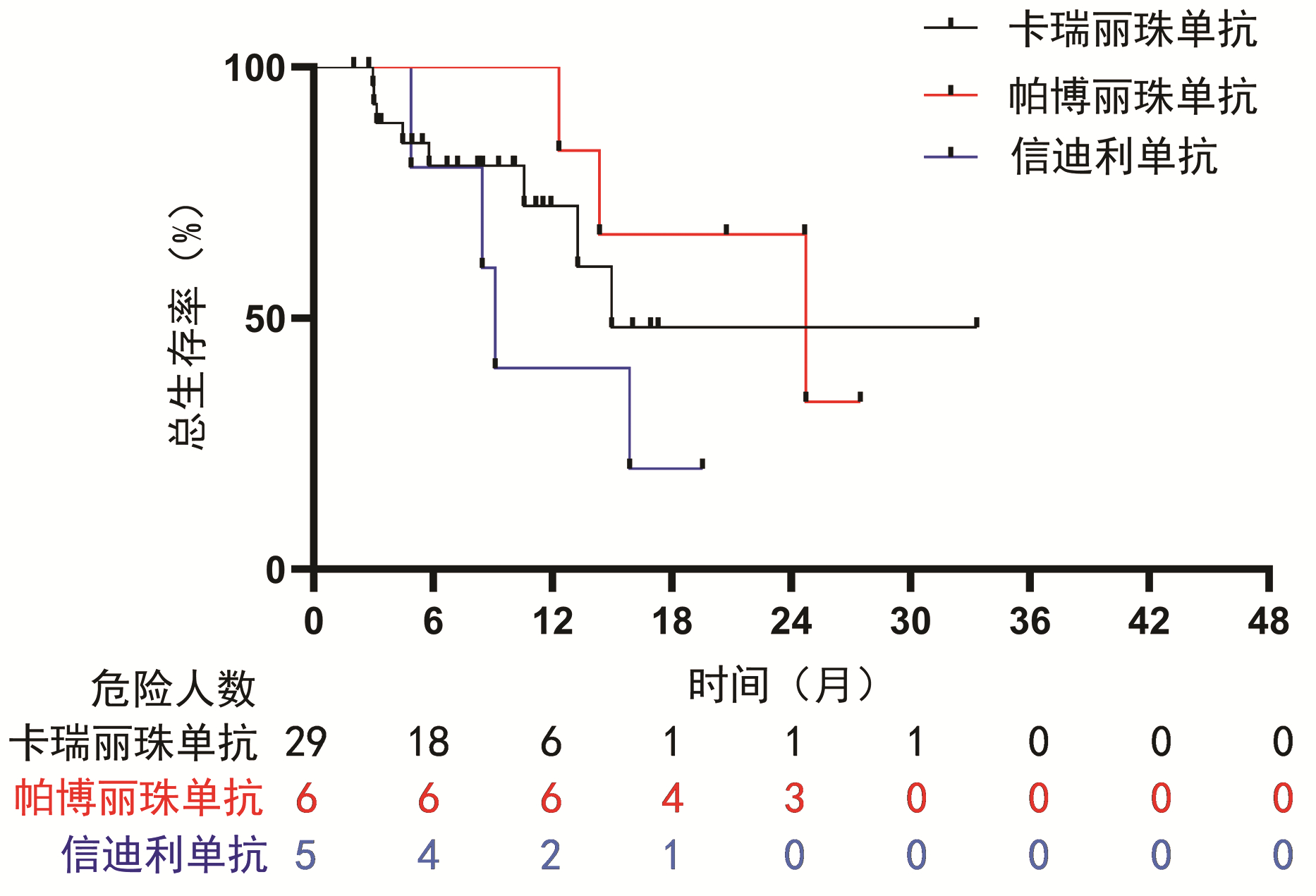

为了探究PD-1抑制剂的使用对联合治疗方式的影响,对使用PD-1抑制剂的HCC患者进行了亚组分析。结果显示:一线使用PD-1抑制剂治疗的HCC患者的中位总生存期为5.8个月(95%CI:0~12.9),二线为15.9个月(95%CI:9.4~22.3),三线为24.7个月,未见明显差异(P=0.368)(图 2)。并且PD-1抑制剂的种类对生存时间的影响没有显著差异(P=0.312)(图 3)。亚组Cox回归分析提示,PD-1抑制剂的使用次数对HCC患者的总生存期有影响(HR=0.93,95%CI:0.86~0.99,P=0.028)。

2.5 不良反应

观察组和对照组中出现的最常见的不良反应均是乏力,最常见的2级以上的不良反应均为手足皮肤反应。观察组和对照组2级以上不良反应率均为40%,未见显著性差异(P=0.818),且2组均未见5级不良反应(表 3)。不良反应经过减少药量和给予对症处理后均好转。

表 3 不良反应情况Table 3. Adverse events不良反应 观察组(n=40) 对照组(n=40) 所有级别 3级 4级 所有级别 3级 4级 乏力[例(%)] 23(57.5) 1(2.5) 0 24(60.0) 3(7.5) 0 腹泻[例(%)] 23(57.5) 2(5.0) 0 20(50.0) 2(5.0) 0 发热[例(%)] 14(35.0) 1(2.5) 0 11(27.5) 2(5.0) 0 高血压[例(%)] 13(32.5) 3(7.5) 0 17(42.5) 3(7.5) 0 手足皮肤反应[例(%)] 11(27.5) 4(10.0) 1(2.5) 15(37.5) 4(10.0) 1(2.5) 皮疹[例(%)] 3(7.5) 2(5.0) 0 3(7.5) 1(2.5) 0 甲状腺功能减退[例(%)] 3(7.5) 1(2.5) 0 1(2.5) 0 0 免疫性肺炎[例(%)] 1(2.5) 0 1(2.5) 0 0 0 3. 讨论

目前,在肝癌的临床治疗中,TACE是应用最为广泛的方法。然而,TACE作为姑息性的治疗手段,有以下缺陷:(1)只是局部治疗,对于门静脉癌栓及肝外转移的病灶几乎没有作用。(2)栓塞后的低氧环境,能诱导肿瘤部位VEGF的合成和分泌,促进新生血管形成,可能引起肿瘤的复发和转移[17]。(3)TACE术后局部缺氧可能会诱导残存肿瘤细胞高表达免疫抑制分子PD-L1, 从而抑制机体的抗肿瘤免疫反应[18]。TACE、抗血管生成药和免疫,三者抗瘤机制不同。根据相关理论研究,三者联合能够取长补短,协同抗癌,弥补单独TACE治疗的缺陷。临床工作中,陆续也有学者将三者联用治疗肝癌。Zheng等[19]的报道表明,对于TACE难治性肝癌患者,TACE+索拉非尼+PD1/PD-L1抑制剂较单独TACE+索拉非尼可以改善患者预后,延长患者生存时间(中位生存时间: 23.3个月vs 13.8个月, P=0.012),两组不良反应发生率未见差异(P=0.421)。但是迄今为止,关于三者联用治疗中晚期不可切除肝癌的相关疗效和安全性的报道尚少,临床医学证据不足。

本回顾性研究总结了本中心所有应用TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂治疗的肝癌患者,并且在同时期仅使用TACE+TKI的患者中随机选取部分患者作为对照组,分析TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂治疗肝癌的有效性及安全性。结果显示在TACE+TKI的基础上加用PD-1抑制剂可以明显改善患者预后,延长患者生存期(15.9个月vs 11.2个月)。与TACE+TKI治疗相比,其严重不良反应发生率未见显著差异,并且通过药物减量和对症治疗使症状均得到缓解,表明联合治疗方式不良反应相对可控。

本研究的单因素与多因素分析显示Child-Pugh分级和血管侵犯是影响TACE+TKI治疗效果的独立危险因素,这与Lencioni等[20]的报道一致。在一定范围内,TACE次数增加是TACE+TKI治疗肝癌患者的保护性因素(HR=0.67,95%CI:0.46~0.99,P=0.043)。TACE是中期肝癌的首选治疗方法[21-22],然而,中期肝癌存在很大的异质性,特别是肿瘤负荷的异质性。在肝功能和体能良好的情况下,肿瘤负荷越重,对TACE治疗反应越差,TACE后复发率也越高[12]。本研究有52例(65%)患者肿瘤负荷较大(超出Up-to-7标准),从理论上讲,肿瘤负荷比较大的患者,通常需要多次TACE治疗[23],部分解释了适当地增加TACE次数可以改善TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂治疗患者的预后。对接受PD-1抑制剂治疗的肝癌患者的亚组分析表明,PD-1抑制剂一线、二线与三线治疗对肝癌患者生存时间的延长没有显著差异,并且不同种类PD-1抑制剂(卡瑞丽珠单抗、帕博丽珠单抗和信迪利单抗)的疗效也未见显著差异。本研究还表明PD-1抑制剂的使用次数与肝癌患者的总生存期呈正相关关系,表明PD-1抑制剂的使用是肝癌患者生存的保护性因素(HR=0.93,95%CI:0.86~0.99,P=0.028)。

本研究具有以下局限性:单中心回顾性研究,样本量较小,可能存在选择性偏倚。受限于回顾性研究的本质,无法做到随机化来控制组间差异,因此进行PSM尽量使组间均衡可比。并且为了减少永久性时间误差,将TACE+TKI的总生存时间减去PD-1抑制剂应用的间隔时间定义为TACE+TKI的生存时间,与TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂的总生存时间进行统计学分析。目前,还有其他很多联合治疗的Ⅲ期临床试验正在进行[24],包括抗血管生成药+免疫治疗和TACE+抗血管生成药+PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂,而且抗血管生成药+免疫治疗的效果已经得到初步证实。研究发现这些组合方法疗效明显,而且相对较安全[25],但TACE+抗血管生成药+PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂的临床试验还在进行中,本研究结论需要在这些临床研究中继续验证。

总之,与TACE+TKI相比,TACE+TKI+PD-1抑制剂可以明显改善中晚期肝癌患者的预后,延长生存期,其不良反应大多在可接受的范围内,为肝癌患者带来新的希望。

-

表 1 患者基线资料

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for the study patients

临床特征 PSM (1∶1匹配)前 PSM(1∶1匹配)后 总计

(n=139)对照组

(n=89)观察组

(n=50)P值 总计

(n=80)对照组

(n=40)观察组

(n=40)P值 男[例(%)] 112(80.6) 72(80.9) 40(80.0) 0.898 63(78.8) 31(77.5) 32(80.0) >0.05 年龄>60岁[例(%)] 46(33.1) 29(32.6) 17(34.0) 0.865 26(32.5) 13(32.5) 13(32.5) 1.000 病因[例(%)] 0.268 0.465 乙型肝炎 119(85.6) 78(87.6) 41(82.0) 69(86.2) 36(90.0) 33(82.5) 丙型肝炎 5(3.6) 4(4.5) 1(2.0) 1(1.2) 0 1(2.5) 其他 15(10.8) 7(7.9) 8(16.0) 10(12.5) 4(10.0) 6(15.0) 靶向药物类型[例(%)] 0.971 >0.05 索拉非尼或仑伐替尼 104(74.8) 66(74.2) 38(76.0) 59(73.8) 30(75.0) 29(72.5) 阿帕替尼或瑞戈非尼 35(25.2) 23(25.8) 12(24.0) 21(26.2) 10(25.0) 11(27.5) Child-Pugh评分[例(%)] 0.898 0.780 A级 112(80.6) 72(80.9) 40(80.0) 64(80.0) 31(77.5) 33(82.5) B级 27(19.4) 17(19.1) 10(20.0) 16(20.0) 9(22.5) 7(17.5) ECOG评分[例(%)] 0.949 0.789 0分 108(77.7) 69(77.5) 39(78.0) 62(77.5) 32(80.0) 30(75.0) 1分 31(22.3) 20(22.5) 11(22.0) 18(22.5) 8(20.0) 10(25.0) BCLC分期[例(%)] 0.961 >0.05 B期 58(41.7) 37(41.6) 21(42.0) 31(38.7) 15(37.5) 16(40.0) C期 81(58.3) 52(58.4) 29(58.0) 49(61.3) 25(62.5) 24(60.0) AFP[例(%)] 0.856 0.819 ≤400 ng/mL 57(41.0) 37(41.6) 20(40.0) 32(40.0) 15(37.5) 17(42.5) >400 ng/mL 82(59.0) 52(58.4) 30(60.0) 48(60.0) 25(62.5) 23(57.5) 腹水[例(%)] 0.767 >0.05 无 115(82.7) 73(82.0) 42(84.0) 65(81.2) 32(80.0) 33(82.5) 少量 24(17.3) 16(18.0) 8(16.0) 15(18.8) 8(20.0) 7(17.5) 肝外转移[例(%)] 0.236 0.823 无 76(54.7) 52(58.4) 24(48.0) 38(47.5) 20(50.0) 18(45.0) 有 63(45.3) 37(41.6) 26(52.0) 42(52.5) 20(50.0) 22(55.0) 血管侵犯[例(%)] 0.683 0.817 无 92(66.2) 60(67.4) 32(64.0) 50(62.5) 24(60.0) 26(65.0) 有 47(33.8) 29(32.6) 18(36.0) 30(37.5) 16(40.0) 14(35.0) Up-to-7标准[例(%)] 0.208 0.482 未超出 57(41.0) 40(44.9) 17(34.0) 28(35.0) 16(40.0) 12(30.0) 超出 82(59.0) 49(55.1) 33(66.0) 52(65.0) 24(60.0) 28(70.0) TACE次数 0.038 0.765 1次 78 55 23 42 20 22 2次 33 21 12 19 10 9 3次 14 6 8 11 7 4 ≥4次 14 7 7 8 3 5 表 2 单因素与多因素分析预后影响因素

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis to explore prognostic factors

临床特征 单因素分析 多因素分析 HR(95%CI) P值 HR(95%CI) P值 应用PD-1抑制剂(ref: 未应用) 0.47(0.26~0.87) 0.017 0.42(0.23~0.80) 0.008 男(ref: 女) 1.21(0.59~2.50) 0.602 年龄>60岁(ref: ≤60岁) 1.27(0.69~2.32) 0.441 病因 乙型肝炎(ref: 其他) 3 007.25(0~2.64×1087) 0.935 丙型肝炎(ref: 其他) 3 060.73(0~2.68×1087) 0.935 索拉非尼和仑伐替尼(ref: 阿帕替尼和瑞戈非尼) 0.84(0.43~1.67) 0.636 Child-Pugh C级(ref: B级) 2.42(1.36~4.70) 0.008 2.40(1.15~5.00) 0.019 ECOG 1分(ref: 0分) 1.41(0.71~2.78) 0.323 BCLC C期(ref: B期) 2.07(1.09~3.91) 0.026 0.85(0.29~2.53) 0.769 AFP>400 ng/mL(ref: ≤400) 1.02(0.57~1.83) 0.952 腹水(ref: 无) 1.88(0.95~3.72) 0.069 肝外转移(ref: 无) 1.82(1.01~3.27) 0.045 0.73(0.21~2.53) 0.617 血管侵犯(ref: 无) 2.30(1.30~4.07) 0.004 3.24(1.11~9.42) 0.031 超过Up-to-7标准(ref: 否) 1.31(0.73~2.38) 0.368 TACE次数每增加1次 0.64(0.46~0.87) 0.005 0.67(0.46~0.99) 0.043 表 3 不良反应情况

Table 3. Adverse events

不良反应 观察组(n=40) 对照组(n=40) 所有级别 3级 4级 所有级别 3级 4级 乏力[例(%)] 23(57.5) 1(2.5) 0 24(60.0) 3(7.5) 0 腹泻[例(%)] 23(57.5) 2(5.0) 0 20(50.0) 2(5.0) 0 发热[例(%)] 14(35.0) 1(2.5) 0 11(27.5) 2(5.0) 0 高血压[例(%)] 13(32.5) 3(7.5) 0 17(42.5) 3(7.5) 0 手足皮肤反应[例(%)] 11(27.5) 4(10.0) 1(2.5) 15(37.5) 4(10.0) 1(2.5) 皮疹[例(%)] 3(7.5) 2(5.0) 0 3(7.5) 1(2.5) 0 甲状腺功能减退[例(%)] 3(7.5) 1(2.5) 0 1(2.5) 0 0 免疫性肺炎[例(%)] 1(2.5) 0 1(2.5) 0 0 0 -

[1] VILLANUEVA A. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(15): 1450-1462. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [2] LLOVET JM, KELLEY RK, VILLANUEVA A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2021, 7(1): 6. DOI: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [3] European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 56(4): 908-943. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [4] LLOVET JM, ZUCMAN-ROSSI J, PIKARSKY E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016, 2: 16018. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [5] FORNER A, REIG M, BRUIX J. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10127): 1301-1314. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [6] VOGEL A, CERVANTES A, CHAU I, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up[J]. Ann Oncol, 2018, 29(Suppl 4): iv238-iv255. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdy308. [7] HARTKE J, JOHNSON M, GHABRIL M. The diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Semin Diagn Pathol, 2017, 34(2): 153-159. DOI: 10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.011. [8] LLOVET JM, REAL MI, MONTAÑA X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2002, 359(9319): 1734-1739. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [9] LO CM, NGAN H, TSO WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2002, 35(5): 1164-1171. DOI: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [10] KIRSTEIN MM, VOIGTLÄNDER T, SCHWEITZER N, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and extrahepatic disease[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2018, 6(2): 238-246. DOI: 10.1177/2050640617716597. [11] RAOUL JL, FORNER A, BOLONDI L, et al. Updated use of TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: How and when to use it based on clinical evidence[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2019, 72: 28-36. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.11.002. [12] WANG Q, XIA D, BAI W, et al. Development of a prognostic score for recommended TACE candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicentre observational study[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(5): 893-903. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.013. [13] KUDO M, UESHIMA K, IKEDA M, et al. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial[J]. Gut, 2020, 69(8): 1492-1501. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318934. [14] PRIETO J, MELERO I, SANGRO B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 12(12): 681-700. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.173. [15] MONTASSER A, BEAUFRÈRE A, CAUCHY F, et al. Transarterial chemoembolisation enhances programmed death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Histopathology, 2021, 79(1): 36-46. DOI: 10.1111/his.14317. [16] JOHN BV, SCHWARTZ K, LEVY C, et al. Impact of obeticholic acid exposure on decompensation and mortality in primary biliary cholangitis and cirrhosis[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2021, 5(8): 1426-1436. DOI: 10.1002/hep4.1720. [17] SUZUKI H, MORI M, KAWAGUCHI C, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor in the course of transcatheter arterial embolization of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Oncol, 1999, 14(6): 1087-1090. DOI: 10.3892/ijo.14.6.1087. [18] NOMAN MZ, DESANTIS G, JANJI B, et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation[J]. J Exp Med, 2014, 211(5): 781-790. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [19] ZHENG L, FANG S, WU F, et al. Efficacy and safety of TACE combined with sorafenib plus immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of intermediate and advanced TACE-refractory hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective Study[J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2021, 7: 609322. DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.609322. [20] LENCIONI R, DE BAERE T, SOULEN MC, et al. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review of efficacy and safety data[J]. Hepatology, 2016, 64(1): 106-116. DOI: 10.1002/hep.28453. [21] HEIMBACH JK, KULIK LM, FINN RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(1): 358-380. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29086. [22] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(1): 182-236. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [23] Bureau of Medical Administration, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer in China (2019 edition)[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2020, 36(2): 277-292. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2020.02.007.中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会医政医管局. 原发性肝癌诊疗规范(2019年版)[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2020, 36(2): 277-292. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2020.02.007. [24] KUDO M. Targeted and immune therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: Predictions for 2019 and beyond[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2019, 25(7): 789-807. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.789. [25] FINN RS, QIN S, IKEDA M, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382(20): 1894-1905. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. 期刊类型引用(7)

1. 石佳鹏,汤小星,赵辉. 程序性死亡受体-1免疫抑制剂在中晚期肝细胞癌中的研究进展. 中国医药导报. 2024(01): 60-63 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 徐静,丁哲,徐颖. 基于TumorFisher CTC检测探讨PD-1/PD-L1免疫抑制剂治疗肝细胞癌的效果. 肝脏. 2024(10): 1184-1188 .  百度学术

百度学术3. 彭翰斐,周志涛,范隼,李庆源,何伟良,钟鹏,卢曼萍,李华,关守海. 药物洗脱微球经动脉化疗栓塞与传统经导管动脉化疗栓塞在晚期肝细胞癌患者治疗中的疗效及安全性评估. 消化肿瘤杂志(电子版). 2024(04): 469-475 .  百度学术

百度学术4. 李承幸,张玉,王芳芳. 乙型肝炎病毒感染患者PBMC表面PD-1、Caspase-9在不同病情阶段中临床表达意义. 医学理论与实践. 2023(05): 838-841 .  百度学术

百度学术5. 刘春华,刘玲,陶昌明,贺玉凯. 仑伐替尼联合阿替利珠单抗序贯TACE治疗乙型肝炎合并晚期肝癌患者的效果评价. 国际医药卫生导报. 2023(11): 1573-1578 .  百度学术

百度学术6. 李琪,颜敏,苏珂,韩云炜,何坤,范娟. TACE术联合TKI及PD-1单抗综合治疗进展期肝癌的临床疗效及安全性分析. 临床和实验医学杂志. 2023(17): 1813-1817 .  百度学术

百度学术7. 陈秋平,邵明义,崔鸿雁,吕兰青,陈晓琦. 度伐利尤单抗联合曲美木单抗一线治疗晚期肝细胞癌的成本-效用分析. 医药导报. 2023(10): 1492-1497 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(3)

-

PDF下载 ( 2633 KB)

PDF下载 ( 2633 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术