利多卡因抑制糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞炎症反应及对肝脓肿形成的影响

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.06.023

Inhibitory effect of lidocaine on Kupffer cell inflammatory response and its effect on liver abscess formation in diabetic mice

-

摘要:

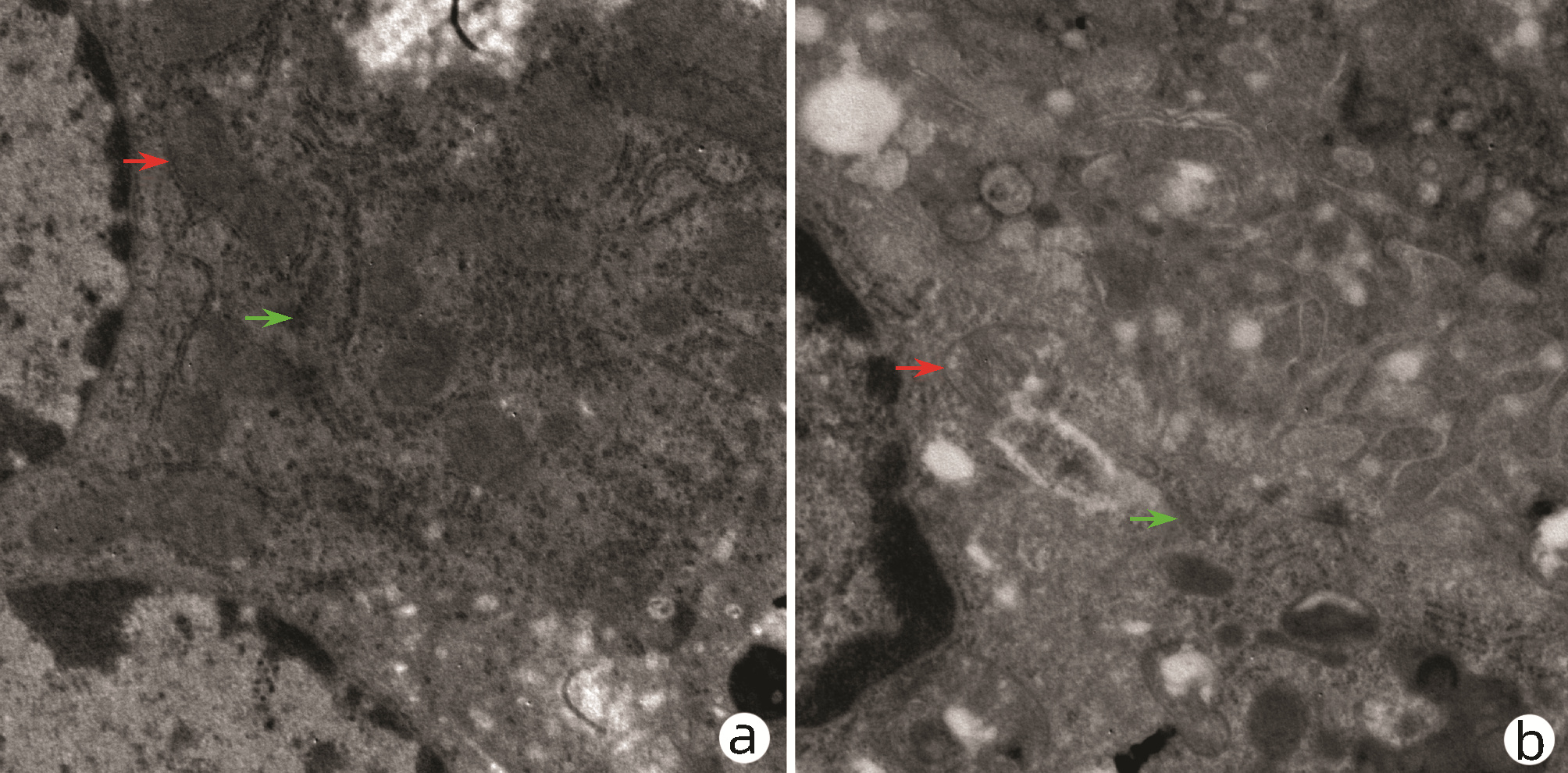

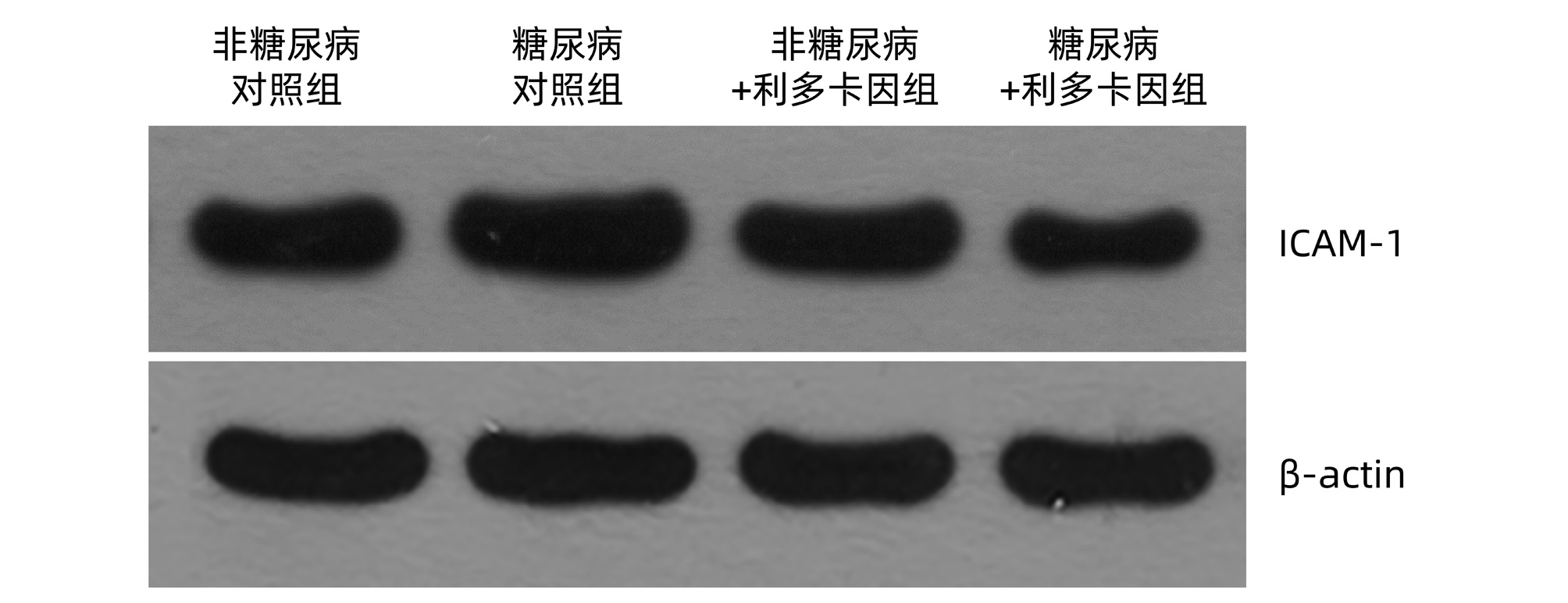

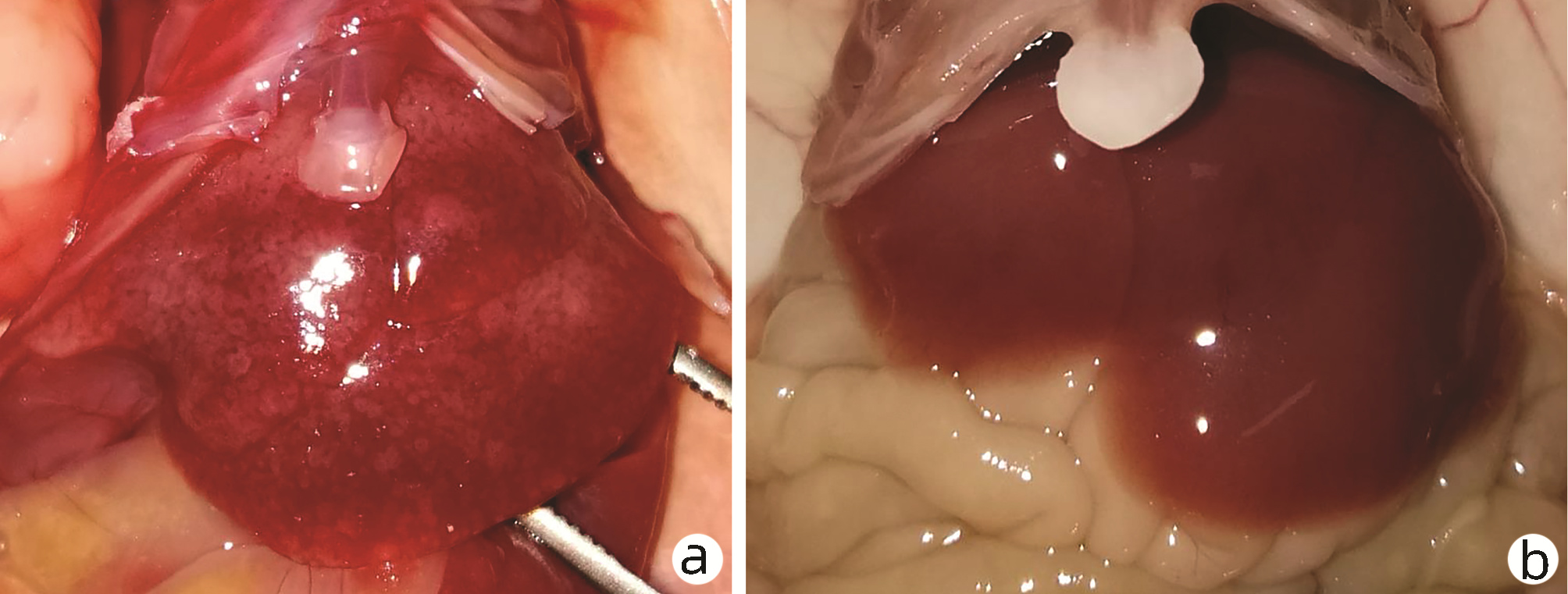

目的 观察利多卡因是否能逆转糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞功能障碍,阐明利多卡因通过改善糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞吞噬功能并影响肝脓肿形成的机制。 方法 将C57BLKS/J db/db小鼠分为糖尿病对照组和糖尿病+利多卡因组,将C57BLKS/J db/m小鼠分为非糖尿病对照组和非糖尿病+利多卡因组,每组5只,均喂食肺炎克雷伯杆菌悬液。分别取Kupffer细胞体外培养,电镜观察超微结构改变,测定Kupffer细胞的炎症介质分泌水平,细胞间黏附分子1(ICAM-1)表达水平,中性粒细胞趋化功能,吞噬功能,以及肝脓肿的形成。计量资料多组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis H秩和检验,进一步两两比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料组间比较采用χ2检验。 结果 糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞中线粒体和粗面内质网的数量减少, 内质网扩张,线粒体肿胀及脂滴增多。与非糖尿病对照组比较,糖尿病对照组Kupffer细胞表达NO[(4.95±0.06) μmol/L vs (1.34±0.13)μmol/L]、IL-6[(740.04±8.58) pg/mL vs (515.77±4.62)pg/mL]、TNFα[(774.23±7.98) pg/mL vs (461.51±1.76)pg/mL]、IFNγ[(842.33±14.79) pg/mL vs (542.47±6.75)pg/mL]、ICAM-1(2.40±0.02 vs 1.33±0.01)水平明显升高(P值均<0.05),中性粒细胞趋化增强(100.80±10.18 vs 13.80±3.70,P<0.05),吞噬能力减弱(9.86±1.82 vs 60.00±3.54,P<0.05),肝脓肿形成无影响(40% vs 0,P>0.05)。与糖尿病对照组比较,糖尿病+利多卡因组Kupffer细胞表达NO[(3.35±0.28) μmol/L vs (4.95±0.06)μmol/L]、IL-6[(688.42±36.34) pg/mL vs (740.04±8.58) pg/mL]、TNFα[(631.15±4.30) pg/mL vs (774.23±7.98) pg/mL]、IFNγ[(704.56±3.64) pg/mL vs (842.33±14.79)pg/mL]、ICAM-1(1.50±0.02 vs 2.40±0.02) 水平明显降低(P值均<0.05),中性粒细胞趋化减弱(33.40±5.60 vs 100.80±10.18,P<0.05),吞噬能力增强(49.20±2.59 vs 9.86±1.82,P<0.05)、肝脓肿形成无影响(0 vs 40%,P>0.05)。 结论 利多卡因可以抑制糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞炎症反应并改善其吞噬功能,对Kupffer细胞起到保护作用,但对肝脓肿的形成无影响。 Abstract:Objective To investigate whether lidocaine can reverse Kupffer cell dysfunction in diabetic mice, as well as the mechanism of lidocaine in affecting liver abscess formation by improving the phagocytic function of Kupffer cells. Methods C57BLKS/J db/db mice were divided into diabetes control group and diabetes+lidocaine group, and C57BLKS/J db/m mice were divided into non-diabetes control group and non-diabetes+lidocaine group, with 5 mice in each group. All mice were fed with the suspension of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Kupffer cells were collected from each group and were cultured in vitro; an electron microscope was used to measure the change in ultrastructure, and Kupffer c ells were measured in terms of the levels of inflammatory mediators, the expression level of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), the chemotactic function of neutrophils, and phagocytic function; liver abscess formation was also observed. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for comparison of continuous data between multiple groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for further comparison between two groups; the chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between groups. Results Compared with the non-diabetic mice, the diabetic mice had significant reductions in mitochondria and rough endoplasmic reticulum, endoplasmic reticulum dilation, mitochondrial swelling, and an increase in lipid droplets in Kupffer cells. Compared with the non-diabetes control group, the diabetes control group had significant increases in the levels of nitric oxide (NO) (4.95±0.06 μmol/L vs 1.34±0.13 μmol/L, P < 0.05), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (740.04±8.58 pg/mL vs 515.77±4.62 pg/mL, P < 0.05), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (774.23±7.98 pg/mL vs 461.51±1.76 pg/mL, P < 0.05), interferon gamma (IFNγ) (842.33±14.79 pg/mL vs 542.47±6.75 pg/mL, P < 0.05), and ICAM-1 (2.40±0.02 vs 1.33±0.01, P < 0.05) in Kupffer cells, a significant increase in neutrophil chemotaxis (100.80±10.18 vs 13.80±3.70, P < 0.05), and a significant reduction in phagocytic capacity (9.86±1.82 vs 60.00±3.54, P < 0.05), with no effect on liver abscess formation (40% vs 0, P > 0.05). Compared with the diabetes control group, the diabetes+lidocaine group had significant reductions in the levels of NO (3.35±0.28 μmol/L vs 4.95±0.06 μmol/L, P < 0.05), IL-6 (688.42±36.34 pg/mL vs 740.04±8.58 pg/mL, P < 0.05), TNFα (631.15±4.30 pg/mL vs 774.23±7.98 pg/mL, P < 0.05), IFNγ (704.56±3.64 pg/mL vs 842.33±14.79 pg/mL, P < 0.05), and ICAM-1 (1.50±0.02 vs 2.40±0.02, P < 0.05) in Kupffer cells, a significant reduction in neutrophil chemotaxis (33.40±5.60 vs 100.80±10.18, P < 0.05), and a significant increase in phagocytic capacity (49.20±2.59 vs 9.86±1.82, P < 0.05), with no effect on liver abscess formation (0 vs 40%, P > 0.05). Conclusion Lidocaine can inhibit Kupffer cell inflammatory response and improve the phagocytic function of Kupffer cells in diabetic mice, thereby exerting a protective effect on Kupffer cells, but it had no effect on liver abscess formation. -

Key words:

- Diabetes Mellitus /

- Liver Abscess /

- Kupffer Cells /

- Lidocaine

-

糖尿病是一种以高血糖为表现的慢性代谢性疾病。据2015年国际糖尿病联合会统计,全球有4.15亿人被诊断出患有糖尿病,500万人死于糖尿病,中国糖尿病患者占全球病例的25%[1]。糖尿病已成为中国公共卫生和经济社会发展的严重负担。糖尿病患者易发多种并发症,其是并发细菌性肝脓肿的最大危险因素[2]。糖尿病患者由于对感染的遗传易感性,且长时间的高血糖改变了细胞和体液免疫防御机制,以及局部血液供应不足和神经损伤,还有与糖尿病相关的代谢改变,从而易发生感染[3]。肝脓肿在糖尿病患者中发病率较高,且致病菌主要为肺炎克雷伯杆菌[4]。肝Kupffer细胞是位于肝窦中的巨噬细胞,其作用是参与清除侵入肝脏的细菌[5]。Kupffer细胞在对抗胃肠道来源的细菌感染方面发挥了重要作用。糖尿病患者Kupffer细胞被激活[6],会释放大量炎症介质[7],如:TNFα、IFNγ、IL和NO等[5, 8]。高血糖还会造成巨噬细胞缺氧应激并损伤其功能[9-11]。因此,肝Kupffer细胞功能障碍可能是糖尿病患者易发肝脓肿的原因之一。利多卡因不仅是常用的局部麻醉药物,其还可以通过作用于NF-κB信号通路,抑制炎症介质释放而达到抗炎作用[12]。但利多卡因是否能改善糖尿病患者的Kupffer细胞功能尚未见报道。为探讨利多卡因对糖尿病肝Kupffer细胞的保护作用及是否会影响肝脓肿的形成,本研究应用利多卡因作用于克雷伯杆菌感染的糖尿病小鼠并体外培养其肝Kupffer细胞,观察利多卡因对其炎症反应的抑制作用及对其吞噬功能的改善情况以及其对肝脓肿形成的影响。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 实验动物及主要试剂

SPF级C57BLKS/J db/db小鼠,C57BLKS/J db/m小鼠各10只,8周龄,雌性,体质量26~28 g,购于常州卡文斯实验动物有限公司,动物生产许可证号: SCXK(苏)2018-0010,动物使用许可证号:SYSK(京)2017-0025。克雷伯杆菌菌株购自上海素冉生物科技有限公司(货号:ATCC13883),利多卡因购自北京紫竹药业有限公司(批号: 20170841)。胎牛血清,DMEM培养基,1640培养基,细胞间黏附分子1(ICAM-1) 单克隆抗体,IL-6,TNFα,IFNγ检测试剂盒购自北京科硕生物技术有限公司(批号: A2040101,20650422,71671025,MA4506,BMS513HS,BMS706-2,PMC5025)。PVDF膜购自中科天锐(北京)科技有限公司(批号: H33072)。聚苯乙烯乳珠购自北京欧北生物科技有限公司(批号: 8002-42-5)。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 细菌培养

菌株复苏后接种于5 mL LB液体培养基,150 r/min振荡培养3~5 h,取100 μL菌液铺于LB固体培养板,倒置于37 ℃孵箱,培养16 h后收集活菌于PBS,紫外分光光度计测定650 nm OD值确定细菌浓度。

1.2.2 试验动物分组及给药

将C57BLKS/J db/db小鼠分为糖尿病对照组和糖尿病+利多卡因组,将C57BLKS/J db/m小鼠分为非糖尿病对照组和非糖尿病+利多卡因组,每组5只。小鼠连续7 d口服20 μL含1×107 CFU高黏性肺炎克雷伯杆菌的悬液,利多卡因干预组给予利多卡因经鼠尾静脉注射(1 mg·kg-1·d-1),连续1周。1周后处死所有小鼠后迅速无菌取出股骨和胫骨及肝脏,肝脏组织病理切片检查有无肝脓肿。

1.2.3 小鼠肝Kupffer细胞及中性粒细胞分离培养

肝脏组织切碎,约1 mm3大小,加入0.1%Ⅳ型胶原蛋白酶37 ℃消化40 min,消化液过滤并离心后用完全培养基(DMEM+10%FBS+1%PBS)重悬。沿离心管壁分别加入3 mL 70%、30%细胞分离液和2 mL上述离心重悬液,400 r/min离心20 min,吸管吸出上层薄层,完全培养基重悬,300 r/min离心5 min,共2次,铺瓶,置于37 ℃,5% CO2培养箱。4 h后除去上清,PBS清洗1遍,去除未贴壁的细胞,贴壁细胞为Kupffer细胞。

取股骨和胫骨剪去两端软骨,露出红色的骨髓腔。1 mL无菌注射器,吸取少量含有10%标准胎牛血清的稀释液,冲洗骨髓腔以获取骨髓。制备成2×108~1×109/mL的单细胞悬液备用。离心管中加入分离液并将细胞悬液平铺到分离液液面上方,离心后出现明显的分层:分离液中为粒细胞层。取细胞用完全培养基(1640+10%FBS+1%PBS)重悬,铺瓶。

1.2.4 透射电镜检测Kupffer细胞细胞器改变

小鼠肝脏组织转移至含有2.5%戊二醛溶液的EP管中,固定1 h,后转移至1 mol/L磷酸盐缓冲液,并洗涤3次,每次5 min。1%锇酸固定30 min,0.1 mol/L磷酸盐缓冲液洗涤2次,每次5 min。3%~4%琼脂预包埋固化后,切成约1 mm3的小块。加入50%、70%、90%乙醇溶液和90%丙酮、10%丙酮脱水。环氧树脂浸渍、包埋、聚合、超片,在FEI Tecnai G212透射电子显微镜下观察。

1.2.5 Griess法检测NO水平

等量细胞培养基与Griess试剂在室温下混合反应20~25 min。546~550 nm波长处读取NO的OD值,计算浓度。

1.2.6 ELISA法定量测定Kupffer细胞的IL-6、TNFα、IFNγ水平

纯化抗体包被微孔板制成固相抗体,微孔中加入标准品或样品及IL-6、TNFα、IFNγ抗体、HRP标记亲和素,彻底洗涤后用底物TMB显色。TMB在过氧化物酶的催化下转化成蓝色,并在酸的作用下转化成黄色。颜色的深浅和样品中的IL-6、TNFα、IFNγ呈正相关。酶标仪在(450±2)nm波长下测定OD值,计算样品浓度。

1.2.7 Western Blot法检测Kupffer细胞ICAM-1表达水平

Kupffer细胞经RIPA裂解缓冲液进行细胞裂解。提取蛋白质通过二辛可宁酸定量分析。样品加到SDS-PAGE凝胶加样孔内,后转移到PVDF膜上。5%脱脂牛奶封闭2 h,37 ℃下与一抗温育过夜。TBS-T洗涤3次,每次10 min,将膜与HRP缀合的二抗在室温下孵育1.5 h。将膜置于免疫印迹仪内,拍照并记录结果。电泳带灰度值扫描,并对目的蛋白半定量分析。以目的条带与内参条带的吸光度比值表示目的蛋白的相对水平。

1.2.8 transwell小室检测中性粒细胞的趋化功能

24孔8.0 μm孔径PC膜transwell小室,每份中性粒细胞悬液加入2个小室。下室加入500 μL细胞密度为2×105/mL各组Kupffer细胞悬液,细胞汇合度达80%后弃去上清,加入500 μL完全培养基(DMEM+10%FBS+1%PBS),上室加入200 μL中性粒细胞悬液(密度为2×105/mL),37 ℃、5% CO2、饱和湿度培养2 h,弃去上室液体,PBS洗涤2遍,棉签擦去上室膜的未趋化细胞,移去小室,倒置并风干。下室加入0.1%结晶紫染液500 μL,37 ℃孵育30 min,弃去染液,PBS洗涤2遍,随机取5个视野,进行中性粒细胞计数。

1.2.9 Kupffer细胞的吞噬功能测定

取接种于盖玻片的Kupffer细胞,每皿加入聚苯乙烯乳珠1×108个,培养60 min,盖玻片PBS漂洗3次,4%多聚甲醛固定30 min,Giemsa染色后倒置显微镜下观Kupffer细胞吞噬聚苯乙烯乳珠情况并计数。每片随机取5个视野,每个视野随机取10个Kupffer细胞进行计数,取每皿Kupffer细胞吞噬聚苯乙烯乳珠数的平均值。

1.3 统计学方法

采用GraphPad Prism 7.0软件进行统计学分析。计量资料采用x±s表示,多组间比较采用Kruskal- Wallis H秩和检验,进一步两两比较采用Mann- Whitney U检验; 计数资料组间比较采用χ2检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 Kupffer细胞超微结构观察

糖尿病小鼠(图 1a)与非糖尿病小鼠(图 1b)比较,Kupffer细胞中细胞核呈椭圆形或肾形,并偶可见核膜断裂,线粒体与粗面内质网的数量减少,并可见粗面内质网扩张,线粒体肿胀及脂滴增多,溶酶体稍有减少。

2.2 各组小鼠Kupffer细胞NO、TNFα、IL-6、IFNγ及ICAM-1表达水平

糖尿病对照组与非糖尿病对照组相比NO、TNFα、IL-6、IFNγ水平均升高(P值均<0.05)(表 1),ICAM-1表达水平亦升高(P<0.05)(表 1,图 2)。与糖尿病对照组比较,糖尿病+利多卡因组NO、TNFα、IL-6、IFNγ水平均降低(P值均<0.05)(表 1),ICAM-1表达水平亦减低(P<0.05)(表 1,图 2)。非糖尿病对照组与非糖尿病+利多卡因组比较各项指标均未见明显变化(P值均>0.05)(表 1,图 2)。

表 1 各组小鼠Kupffer细胞NO、IL-6、TNFα、IFNγ、ICAM-1水平Table 1. Levels of NO, IL-6, TNFα, IFNγ and ICAM-1 in Kupffer cells of mice in each group指标 非糖尿病对照组

(n=5)糖尿病对照组

(n=5)非糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)H值 P值 NO(μmol/L) 1.34±0.13 4.95±0.061) 1.47±0.16 3.35±0.282) 16.50 <0.001 IL-6(pg/mL) 515.77±4.62 740.04±8.581) 512.79±2.24 688.42±36.342) 15.79 0.001 TNFα(pg/mL) 461.51±1.76 774.23±7.981) 468.48±7.42 631.15±4.302) 16.71 <0.001 IFNγ(pg/mL) 542.47±6.75 842.33±14.791) 543.49±8.38 704.56±3.642) 16.07 0.001 ICAM-1 1.33±0.01 2.40 ±0.021) 1.31±0.03 1.50±0.022) 16.52 0.001 注:与非糖尿病对照组相比,1)P<0.05;与糖尿病对照组相比,2)P<0.05。 2.3 各组小鼠中性粒细胞趋化和Kupffer细胞吞噬功能

糖尿病对照组与非糖尿病对照组相比,中性粒细胞趋化增强(P<0.05)(表 2,图 3a、b),糖尿病+利多卡因组与糖尿病对照组相比,中性粒细胞趋化减弱(P<0.05)(表 2,图 3b、d),非糖尿病对照组与非糖尿病+利多卡因组相比,中性粒细胞趋化无统计学差异(P>0.05)(表 2,图 3a、c)。糖尿病组与非糖尿病对照组相比,Kupffer细胞吞噬能力减弱(P<0.05)(表 2,图 4a、b),糖尿病+利多卡因组与糖尿病对照组相比,Kupffer细胞吞噬能力增强(P<0.05)(表 2,图 4b、d),非糖尿病对照组与非糖尿病+利多卡因组相比,Kupffer细胞吞噬能力无统计学差异(P>0.05)(表 2,图 4a、c)。

表 2 各组小鼠中性粒细胞招募、吞噬功能水平Table 2. Neutrophil recruitment and phagocytic function levels in each group项目 非糖尿病对照组

(n=5)糖尿病对照组

(n=5)非糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)H值 P值 中性粒细胞趋化 13.80±3.70 100.80±10.181) 14.40±4.67 33.40±5.602) 16.12 0.001 Kupffer细胞吞噬功能 60.00±3.54 9.86 ±1.821) 62.60±1.95 49.20±2.592) 16.87 0.001 注:与非糖尿病对照组相比,1)P<0.05;与糖尿病对照组相比,2)P<0.05。 2.4 各组小鼠肝脓肿形成

糖尿病对照组小鼠形成2例(40%)肝脓肿, 余各组均无肝脓肿形成(图 5),各组相比差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

3. 讨论

2019年全球约4.63亿20~79岁成人罹患糖尿病,预计到2030年,糖尿病患者将达到5.784亿; 中国是糖尿病患者数量最多的国家[13]。糖尿病患者由于多有免疫功能障碍,神经病变和血液循环不良,因此容易促进细菌生长导致感染的发生[14-15]。与正常人相比,糖尿病患者发生化脓性肝脓肿的风险增加35.3%[16]。糖尿病相关肝脓肿的致病菌主要为肺炎克雷伯杆菌,这可能与糖尿病患者血管内膜异常,易使获得性肺炎克雷伯杆菌发生血源性播散有关[17-18]。Kupffer细胞是肝血窦内的巨噬细胞,是病原体进入肝脏的第一道防线,参与清除入侵肝窦的细菌和病毒[5, 15, 19]。本研究通过透射电镜观察了糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞的线粒体、溶酶体和粗面内质网,发现它们的数量明显低于非糖尿病小鼠且质量不佳。因炎症反应与应激信号可以通过内质网影响细胞代谢,因此内质网改变在2型糖尿病的发展过程中也起到了一定的作用[20]。线粒体和内质网的数量减少可能意味着Kupffer细胞的功能减弱[21]。因此患有糖尿病的小鼠,其Kupffer细胞的功能受到了显著影响。同时由于糖尿病小鼠的Kupffer细胞功能紊乱,吞噬能力明显低于非糖尿病小鼠。此前的研究也证实高血糖可通过缺氧应激导致巨噬细胞功能受到抑制[9-11]。

糖尿病患者微环境通常处于异常的全身慢性炎症反应状态[22-24],其体内Kupffer细胞被内毒素、TNF等激活,并大量释放TNFα、TGF、IFN、IL、氧自由基、NO等炎症介质[5, 8]。静息状态下Kupffer细胞表面ICAM-1呈低表达,但可通过炎症介质上调其表达[25]。本研究发现糖尿病小鼠中Kupffer细胞表面的ICAM-1呈高表达,因此证实糖尿病小鼠的Kupffer细胞处于激活状态。糖尿病组与非糖尿病组小鼠相比其Kupffer细胞中NO、IL-6、IFNγ和TNFα的分泌增加,ICAM-1的表达增强。因此,糖尿病小鼠的Kupffer细胞处于激活状态,与糖尿病是一种由于营养代谢异常导致的全身性慢性炎症性疾病的认知相符[22, 24],而转录因子NF-κB在糖尿病和慢性炎症的发生发展中发挥了重要作用[26-27]。

利多卡因被广泛用作局麻药和抗心律失常药。有研究表明利多卡因对血管系统有保护作用[28-29],并可抑制炎症因子的表达[12],还具有抗肿瘤作用。通常认为局麻药具有良好的抗炎作用,其可减弱炎性Src信号并抑制PI3K-Akt-NO通路,从而可阻断Src依赖的中性粒细胞粘附和内皮细胞高通透性[28]。利多卡因可通过调节NF-κB信号通路,抑制细胞炎症反应[9],还可通过抑制炎症介质来保护内皮细胞功能[28]。本研究发现利多卡因可抑制糖尿病小鼠炎症介质的释放,下调了其Kupffer细胞表面ICAM-1的表达,并减少了粒细胞招募,同时也改善了糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞的吞噬能力。由此认为利多卡因可能通过调节NF-κB信号通路改善糖尿病小鼠的全身性炎症反应状态,使糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞由激活状态调整为静息状态,并使其吞噬能力得到改善; 提示利多卡因对糖尿病小鼠Kupffer细胞起到了一定程度的保护作用。但在本研究中利多卡因并未显示可减少糖尿病小鼠肝脓肿形成的风险。

本研究的主要局限性包括样本量相对较小和对假设的分子机制缺乏功能验证。ICAM-1表达只检测到了翻译水平,而不是转录水平。而小鼠细菌性肝脓肿模型的建立因样本量较少也缺乏代表性。

综上所述,糖尿病小鼠的Kupffer细胞激活招募粒细胞,显著地释放炎症介质且有吞噬功能的障碍,而利多卡因具有恢复吞噬功能和抑制炎症介质释放的作用,但对细菌性肝脓肿的形成并没有明显的改善作用。

-

表 1 各组小鼠Kupffer细胞NO、IL-6、TNFα、IFNγ、ICAM-1水平

Table 1. Levels of NO, IL-6, TNFα, IFNγ and ICAM-1 in Kupffer cells of mice in each group

指标 非糖尿病对照组

(n=5)糖尿病对照组

(n=5)非糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)H值 P值 NO(μmol/L) 1.34±0.13 4.95±0.061) 1.47±0.16 3.35±0.282) 16.50 <0.001 IL-6(pg/mL) 515.77±4.62 740.04±8.581) 512.79±2.24 688.42±36.342) 15.79 0.001 TNFα(pg/mL) 461.51±1.76 774.23±7.981) 468.48±7.42 631.15±4.302) 16.71 <0.001 IFNγ(pg/mL) 542.47±6.75 842.33±14.791) 543.49±8.38 704.56±3.642) 16.07 0.001 ICAM-1 1.33±0.01 2.40 ±0.021) 1.31±0.03 1.50±0.022) 16.52 0.001 注:与非糖尿病对照组相比,1)P<0.05;与糖尿病对照组相比,2)P<0.05。 表 2 各组小鼠中性粒细胞招募、吞噬功能水平

Table 2. Neutrophil recruitment and phagocytic function levels in each group

项目 非糖尿病对照组

(n=5)糖尿病对照组

(n=5)非糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)糖尿病+利多

卡因组(n=5)H值 P值 中性粒细胞趋化 13.80±3.70 100.80±10.181) 14.40±4.67 33.40±5.602) 16.12 0.001 Kupffer细胞吞噬功能 60.00±3.54 9.86 ±1.821) 62.60±1.95 49.20±2.592) 16.87 0.001 注:与非糖尿病对照组相比,1)P<0.05;与糖尿病对照组相比,2)P<0.05。 -

[1] NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population- based studies with 4.4 million participants[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10027): 1513-1530. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [2] FENG J. Retrospective analysis of clinical features and risk factors of patients with diabetic bacterial hepatic abscess complicated with hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases[J]. J Hepatobiliary Surg, 2020, 28(6): 423-426. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4761.2020.06.008.冯静. 回顾性分析糖尿病细菌性肝脓肿患者合并肝胆胰疾病的临床特点及危险因素[J]. 肝胆外科杂志, 2020, 28(6): 423-426. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4761.2020.06.008. [3] ATREJA A, KALRA S. Infections in diabetes[J]. J Pak Med Assoc, 2015, 65(9): 1028-1030. [4] PAN JZ, WANG XM, HUANG YQ, et al. Clinical analysis of 424 cases of diabetes mellitus complicated with bacterial liver abscess[J]. Chin J Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 14(3): 199-202. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2021.03.007.潘教治, 王仙敏, 黄友全, 等. 糖尿病合并细菌性肝脓肿424例临床分析[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2021, 14(3): 199-202. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2021.03.007. [5] WOHLLEBER D, KNOLLE PA. The role of liver sinusoidal cells in local hepatic immune surveillance[J]. Clin Transl Immunology, 2016, 5(12): e117. DOI: 10.1038/cti.2016.74. [6] DONG B, ZHOU Y, WANG W, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation in liver macrophages ameliorates hepatic inflammation, steatosis, and insulin resistance in mice[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 71(5): 1559-1574. DOI: 10.1002/hep.30937. [7] HOTAMISLIGIL GS. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders[J]. Nature, 2017, 542(7640): 177-185. DOI: 10.1038/nature21363. [8] BILZER M, ROGGEL F, GERBES AL. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease[J]. Liver Int, 2006, 26(10): 1175-1186. DOI: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01342.x. [9] DASU MR, DEVARAJ S, ZHAO L, et al. High glucose induces toll-like receptor expression in human monocytes: Mechanism of activation[J]. Diabetes, 2008, 57(11): 3090-3098. DOI: 10.2337/db08-0564. [10] KANETO H, KATAKAMI N, MATSUHISA M, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in the progression of type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2010, 2010: 453892. DOI: 10.1155/2010/453892. [11] TABET F, LAMBERT G, CUESTA TORRES LF, et al. Lipid-free apolipoprotein A-I and discoidal reconstituted high-density lipoproteins differentially inhibit glucose-induced oxidative stress in human macrophages[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2011, 31(5): 1192-1200. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.222000. [12] YUAN T, LI Z, LI X, et al. Lidocaine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in microglia[J]. J Surg Res, 2014, 192(1): 150-162. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.05.023. [13] International Diabetes Federation: A global emergency. IDF diabetes atlas seventh edition[C]. Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015: 11-13. [14] PEARSON-STUTTARD J, BLUNDELL S, HARRIS T, et al. Diabetes and infection: Assessing the association with glycaemic control in population-based studies[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2016, 4(2): 148-158. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00379-4. [15] BALMER ML, SLACK E, de GOTTARDI A, et al. The liver may act as a firewall mediating mutualism between the host and its gut commensal microbiota[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2014, 6(237): 237ra66. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008618. [16] CHEN YC, LIN CH, CHANG SN, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of pyogenic liver abscess: An analysis from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan, 2000-2011[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2016, 49(5): 646-653. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.08.028. [17] FOO NP, CHEN KT, LIN HJ, et al. Characteristics of pyogenic liver abscess patients with and without diabetes mellitus[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2010, 105(2): 328-335. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2009.586. [18] SOHN SH, KIM KH, PARK JH, et al. Predictors of mortality in Korean patients with pyogenic liver abscess: A single center, retrospective study[J]. Korean J Gastroenterol, 2016, 67(5): 238-244. DOI: 10.4166/kjg.2016.67.5.238. [19] GREGORY SH, COUSENS LP, van ROOIJEN N, et al. Complementary adhesion molecules promote neutrophil-Kupffer cell interaction and the elimination of bacteria taken up by the liver[J]. J Immunol, 2002, 168(1): 308-315. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.308. [20] OZCAN U, CAO Q, YILMAZ E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes[J]. Science, 2004, 306(5695): 457-461. DOI: 10.1126/science.1103160. [21] LOHMANN-MATTHES ML, STEINMVLLER C, FRANKE-ULLMANN G. Pulmonary macrophages[J]. Eur Respir J, 1994, 7(9): 1678-1689. [22] GALASSETTI P. Inflammation and oxidative stress in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes[J]. Exp Diabetes Res, 2012, 2012: 943706. DOI: 10.1155/2012/943706. [23] HOTAMISLIGIL GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders[J]. Nature, 2006, 444(7121): 860-867. DOI: 10.1038/nature05485. [24] ESSER N, LEGRAND-POELS S, PIETTE J, et al. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2014, 105(2): 141-150. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.006. [25] DUSTIN ML, ROTHLEIN R, BHAN AK, et al. Induction by IL 1 and interferon-γ: Tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function of a natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1)[J]. J Immunol, 1986. 137: 245-254. [26] BAKER RG, HAYDEN MS, GHOSH S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease[J]. Cell Metab, 2011, 13(1): 11-22. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [27] KAUPPINEN A, SUURONEN T, OJALA J, et al. Antagonistic crosstalk between NF-κB and SIRT1 in the regulation of inflammation and metabolic disorders[J]. Cell Signal, 2013, 25(10): 1939-1948. DOI: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.007. [28] PIEGELER T, VOTTA-VELIS EG, BAKHSHI FR, et al. Endothelial barrier protection by local anesthetics: Ropivacaine and lidocaine block tumor necrosis factor-α-induced endothelial cell Src activation[J]. Anesthesiology, 2014, 120(6): 1414-1428. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000174. [29] PIEGELER T, VOTTA-VELIS EG, LIU G, et al. Antimetastatic potential of amide- linked local anesthetics: Inhibition of lung adenocarcinoma cell migration and inflammatory Src signaling independent of sodium channel blockade[J]. Anesthesiology, 2012, 117(3): 548-559. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182661977. 期刊类型引用(1)

1. 关敬,哈森,袁颢,陈颖,刘鹏举,刘智,姜爽. 小陷胸汤加味方对2型糖尿病大鼠肝损伤的保护作用及其机制. 吉林大学学报(医学版). 2023(03): 608-616 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(1)

-

PDF下载 ( 3726 KB)

PDF下载 ( 3726 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术