转化生长因子β在胰腺癌发生发展中的作用

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.12.041

Role of transforming growth factor-β in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer

-

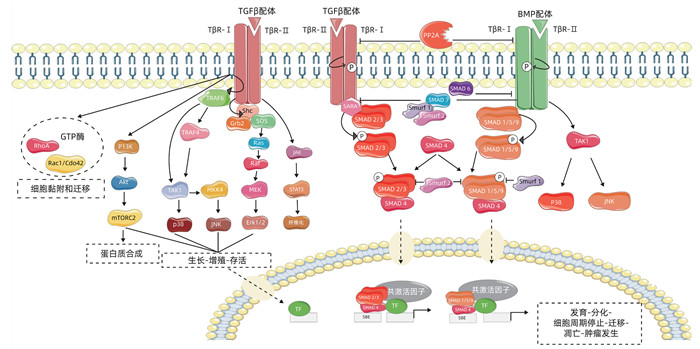

摘要: 胰腺导管腺癌恶性程度高,起病隐匿,病情进展快,在早期无明显的腹部表现及体征。多数患者就诊时已发展为中晚期,并常伴远处脏器转移,因此手术治疗、放化疗及药物靶向治疗效果通常不佳。近年来研究表明,转化生长因子β(TGFβ)与肿瘤的发生、发展密不可分,在肿瘤细胞的增殖、侵袭、迁移和血管的生成等进程中发挥关键性的调节作用。尽管TGFβ信号能够利用SMAD介导的细胞周期阻滞起到强大的肿瘤抑制作用,但是TGFβ信号也可以通过增强上皮-间质转化、纤维化和免疫逃逸来加速胰腺癌的发生。本文所述胰腺癌均特指为胰腺导管腺癌,旨在对TGFβ在其信号传导中的作用及其相关因子和免疫反应等方面关系的研究予以综述,为今后胰腺癌的靶向治疗提供理论依据。Abstract: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma has a high degree of malignancy, an insidious onset, and rapid progression, with no obvious abdominal manifestations and signs in the early stage. Most patients are already in the advanced stage and have distant organ metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and thus surgical treatment, chemoradiotherapy, and targeted drug therapy often have an unsatisfactory clinical effect. Recent studies have shown that transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is closely associated with the development and of tumors and plays a key role in the processes of tumor cell proliferation, invasion, migration, and angiogenesis. Although TGF-β signal can exert a powerful inhibitory effect on tumors through SMAD-mediated cell cycle arrest, TGF-β signal can also accelerate the development of pancreatic cancer by enhancing epithelial-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis, and immune escape. In this article, pancreatic cancer specifically refers to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and this article reviews the role of TGF-β in its signal transduction and the association of TGF-β with related factors and immune response, so as to provide a theoretical basis for targeted therapy for pancreatic cancer in the future.

-

肝硬化是临床常见的慢性进行性肝病,引起肝硬化的病因有很多,欧美国家以酒精性肝硬化为主,而我国是以乙型肝炎引发的肝硬化为主,肝硬化患者的HBsAg阳性率高达76.7%[1],其形成机制主要是由于肝炎病毒感染导致广泛性肝细胞变性坏死、肝小叶结构破坏、肝脏弥漫性纤维化、结节性再生同时伴有假小叶形成,肝脏逐渐变形、变硬而发展为肝硬化。常选用保肝、降酶、退黄等基础治疗,而终末期肝硬化临床治疗效果差,缺乏广泛可行的治疗手段。干细胞移植的出现, 以其独特的生物学特性,为肝病治疗带来新的治疗思路。

脐带血中造血干细胞含量丰富,其增殖能力是成人骨髓造血干细胞的数倍[2],近年来国内外多项研究证实人脐带血单个核细胞(human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells, hUCB-MNCs)移植对肝硬化也有显著的辅助治疗效果[3]。

过去认为,骨髓间充质干细胞(bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells,BMSCs)治疗肝脏疾病趋向于受损的肝脏区域而后分化成肝细胞、修复受损肝细胞或通过免疫调节抑制炎性反应,促进肝功能恢复,但采集大量的骨髓多数患者很难接受,从而限制了临床的广泛应用。而人脐带组织来源的间充质干细胞(human umbilical cord msenchymal stem cells, hUC-MSCs),取材方便,较BMSCs有更高的增殖、分化潜能和免疫调节功能,其免疫原性远低于BMSCs[4],具有更加广泛的临床应用与研究价值[5]。为了提高肝硬化疗效,本研究采用了hUCB-MNCs联合hUC- MSCs治疗肝硬化,笔者前期临床研究发现,hUCB-MNCs具有极其良好的提高患者免疫的功效[6],因此先行输注hUCB-MNCs,改善患者整体状况,提高其免疫功能。而后输入hUC-MSCs,使其归巢到肝脏,分化为肝细胞或进入肝脏后修复受损的肝细胞[7-9],并可通过某些细胞因子的改变, 来调节免疫、减轻炎症反应、抗肝细胞凋亡、促进血管增生、抗肝纤维化等修复损伤肝组织,同时促进hUC-MSCs的多向分化[10-12]。两种细胞联合治疗,以更好的发挥其疗效。本研究为单中心、回顾性、非随机、自体对照临床研究。通过观察联合输注治疗肝硬化后各项指标的改变,对其治疗肝硬化的免疫调节及安全性进行评价,为肝硬化的治疗探索新的治疗方法。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

脐带血全部来源于山东省齐鲁干细胞库;脐带采集于内蒙古医科大学附属医院妇产科,选取经剖宫产足月健康胎儿的脐带,并征得父母授权同意,4 ℃预冷生理盐水密闭容器保存。MSCs所用无血清培养基购自Invitrogen, USA、流式细胞分析仪所用单克隆抗体购自美国BD公司;ELISA试剂盒购自上海润裕生物公司。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 研究对象

选取2016年11月—2019年6月内蒙古医科大学附属医院收治的失代偿性肝硬化患者,纳入标准:(1)诊断符合2000年中华医学会肝病学分会修订的《病毒性肝炎防治方案》[13]、2005年中华医学会肝病学分会修订的《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南》的肝硬化临床诊断标准[14],诊断为乙型肝炎肝硬化,且Child-Pugh分级为B、C级(失代偿期肝硬化);(2)年龄40~60岁;(3)在加入本研究之前,理解并签署知情同意书,并且遵守研究方案的要求;同意不参加其他任何临床研究。排除标准:(1)除肝衰竭或肝硬化失代偿以外的任何严重的全身性疾病,研究者认为可能会干扰受试者的治疗或干扰受试者的依从性,包括任何未被控制的具有临床意义的泌尿、循环、呼吸、神经、精神、消化、内分泌、免疫等系统疾病及肿瘤等;(2)肝静脉或门静脉血栓形成;(3)HIV抗体阳性者;(4)筛选前3个月内接受过其他药物的临床研究;(5)1年内有酗酒或有静脉药瘾者;(6)HBV DNA>200 IU/ml;(7) 肾衰竭,血肌酐>451 mol/L;(8)肺功能指标,FEV1<35%,DLCO-SB<39%;(9)根据AHA 1994年心功能标准D级;(10)其他可能妨碍临床研究的严重情况。最终纳入肝硬化患者11例,根据患者整体状况进行Child- Pugh分级[15](表 1)。入组的肝硬化患者经常规治疗(保肝、降黄疸、降血氨、抗病毒、抗感染、必要时输白蛋白等对症支持处理,同时静脉注射促肝细胞生长素80 mg/d),治疗4周后效果不佳(即肝功能、血氨、凝血因子、血清细胞因子浓度及淋巴细胞亚群的无变化,且神经、精神症状未改善者),患者自愿申请参加本研究。

表 1 入组患者的信息和条件患者 年龄(岁) 性别 腹水 TBil(μmol/L) Alb(g/L) PT(s) Child-Pugh分级 No.1 50 男 - 48.1 26.5 19.3 B级 No.2 48 男 - 47.9 22.9 19.9 B级 No.3 55 男 Ⅰ 47.4 24.8 22.5 B级 No.4 56 男 - 34.9 26.0 22.9 B级 No.5 60 男 Ⅰ 54.4 22.8 20.5 C级 No.6 52 女 - 48.5 31.9 20.2 B级 No.7 41 男 - 43.8 40.8 19.4 B级 No.8 49 男 - 50.2 23.9 17.2 B级 No.9 51 男 Ⅰ 34.8 27.4 16.2 B级 No.10 53 男 Ⅱ 67.6 22.6 19.4 C级 No.11 51 男 Ⅰ 48.7 21.9 19.4 B级 1.2.2 hUCB-MNCs制备

采集患者外周血,送山东省齐鲁干细胞库进行HLA血清和基因分型,选择至少4个位点相合的脐带血作为供者,然后将从脐带血分离获取的hUCB-MNCs(山东省齐鲁干细胞库操作制备)悬浮于含有2%人血白蛋白的0.9%生理盐水(150 ml)备用。

1.2.3 hUC-MSCs制备

脐带标本采集后至于4 ℃预冷生理盐水密闭容器中,6 h内完成分离脐带中华通氏胶,用MSCs无血清培养基培养制备hUC-MSCs,连续传代培养,取P3代hUC-MSCs,应用流式细胞仪检测细胞表面标记CD34、CD44、CD90、CD105和HLA-DR的表达情况。台盼蓝染色活性检测>95%,细胞HIV、EB病毒、HBV、HCV核酸分别用PCR和逆转录PCR(RT-PCR)检测,检测无任何微生物污染。最后制备的hUC-MSCs, 用含有2%人血白蛋白的0.9%生理盐水(150 ml)来悬细胞备用。

1.2.4 hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs输注方案

患者经常规治疗后,临床检测肝肾功能、生化指标、肿瘤标志物、临床评估心肺功能、神经、精神状况达到入组标准。本研究方案为:第1周输注1次hUCB-MNCs(>18×109/次),第2、3、4周每周1次,每次输入hUC-MSCs 1×106/kg,每个患者3次输注的hUC-MSCs为同一来源的脐带所分离培养。为了防止可能发生的过敏反应,输注前5 min静脉输入5 mg地塞米松。hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs回输结束第4、8、12周后跟踪随访。

1.2.5 hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs输注的不良反应、实验室检查及疗效评估

一个治疗方案结束后,有1例患者(No.5)腋下体温38.1 ℃,持续时间为2 h,患者自行服用布洛芬,大量饮用温开水发汗,排尿后体温降到正常。在之后的随访过程中,所有患者均未出现明显副作用;hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs回输结束第4、8、12周后采集静脉血,检测肝功能、血氨、凝血功能等各项指标,比较输注前后及输注不同时间后指标变化;同时对比观察治疗前后患者神经、精神状况,根据患者整体状况进行Child-Pugh肝功能分级。

1.2.6 细胞输注后免疫细胞及细胞因子定量检测

患者在细胞治疗疗程结束4周后开始检测淋巴细胞亚群和血清细胞因子。流式细胞仪测定CD3+T淋巴细胞、CD3+CD4+T淋巴细胞、CD3+CD8+T淋巴细胞、CD4+CD25+调节性T淋巴细胞(Treg)、CD19+B淋巴细胞百分率;ELISA试剂盒量检测血清IL-6、TNF、IL-10、TGFβ。

1.3 伦理学审查

本研究获得内蒙古医科大学附属医院伦理委员会批准,批号:2017医第(028)号。所纳入患者均签署知情同意书。

1.4 统计学方法

采用SPSS 23.0统计学软件进行数据分析。计量资料以x±s表示,不同时间点比较采用单因素重复测量方差分析。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

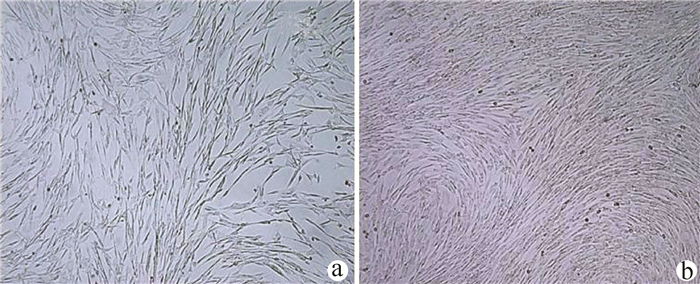

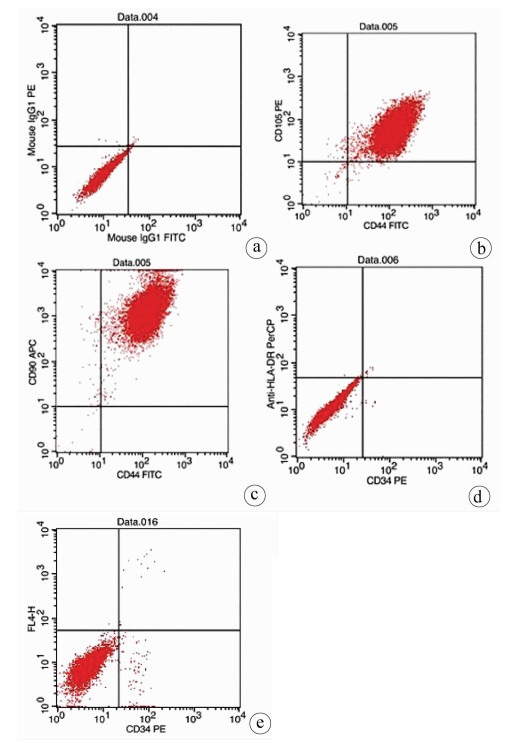

2.1 hUC-MSCs的鉴定

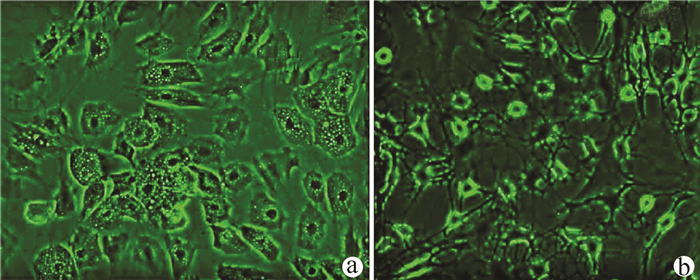

实验室制备的hUC-MSCs呈贴壁生长,外形为均匀梭形(图 1),流式细胞分析检测,CD44、CD90和CD105表达均>98%(阳性)(图 2b、2c),而CD34和HLA-DR表达为阴性(图 2d);山东省齐鲁干细胞库提供的hUCB-MNCs总数>1.8×109;台盼蓝染色显示活性>95%;血清学和基因HLA分型,供体与受体至少有4个位点相合(山东省齐鲁干细胞库提供),无任何可检测到的微生物污染,对山东脐血库提供的细胞再次进行了流式细胞分析,检测显示其中CD34+细胞>1.5%(图 2e);制备的hUC-MSCs可以被诱导成肝细胞、神经细胞(图 3);常规和核酸PCR/RT-PCR检测无任何微生物污染;裸鼠实验证实无致瘤性;hUC-MSCs活性>95%。

2.2 hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs输注前后及不同时间对肝功能、血氨及其他状况的影响

在hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs输注结束后,对PT和PTA影响最快,细胞输注结束后第4周即可显著改善(P值均<0.05),而患者的肝功能酶学指标在细胞输注后第8周逐渐恢复到正常水平(P值均<0.05),在输注结束第12周时,肝功能指标较之前明显好转(P值均<0.01)(表 2)。

表 2 细胞输注前后肝功能变化输注时间 ALT(U/L) AST(U/L) ALP(U/L) GGT(U/L) TBil(μmol/L) Alb(g/L) PTA(%) PT(s) 输注前 88.4±15.31) 99.8±25.01) 123.8±39.41) 305.1±83.41) 47.8±8.11) 26.5±6.41) 45.8±7.91) 16.2±1.31) 输注(4周) 77.9±22.7 85.5±31.3 97.5±40.1 189.1±66.4 23.2±9.8 30.5±3.6 66.0±6.0 12.6±0.5 输注(8周) 59.1±21.5 26.8±7.9 58.1±17.6 86.6±39.9 9.9±5.3 36.0±4.2 74.9±6.9 12.2±1.8 输注(12周) 42.7±12.3 24.2±8.3 59.5±28.0 43.2±19.8 6.7±1.8 40.8±2.4 87.6±3.0 11.3±0.2 F值 14.496 41.163 10.941 45.740 79.730 20.496 86.289 1 029.600 P值 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 <0.05 注:与输注后的第4、8、12周比较, 1)P<0.05。 细胞输注4周后,患者血清中血氨浓度明显降低(P<0.05),随着时间的延长,血氨水平持续下降,除患者No. 7、10、11外,其他患者在hUCB-MNCs和HUC-MSCs输注12周后均降低到正常水平(P值均<0.05)(表 3)。

表 3 hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs输注前后血氨值变化输注时间 血氨(μmol/L) 输注前 166.6±47.71) 输注(4周) 115.6±32.8 输注(8周) 87.2±36.3 输注(12周) 66.2±32.5 F值 104.6 P值 P<0.05 注:与输注后的第4、8、12周比较, 1)P<0.05。 细胞输注后第4、8周,5例肝硬化腹水患者的腹水均有所减少,除却No.10患者仍有少量腹水,且Child-Pugh分级仍然处于C级。10例患者的乏力、食欲、睡眠、精神、腹胀、下肢水肿等明显改善,血清胆红素及PT基本恢复正常,血清Alb也明显升高,Child-Pugh评分随之降低,差异有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)(表 4)。

表 4 hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs输注前后Child-Pugh评分变化输注时间 Child-Pugh评分 输注前 10.10±2.431) 输注(4周) 8.36±2.94 输注(8周) 6.82±2.27 输注(12周) 6.09±1.58 F值 68.4 P值 P<0.05 注:与输注后的第4、8、12周比较, 1)P<0.05。 2.3 hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs输注对血清细胞因子和淋巴细胞亚群的影响

采集患者静脉血,ELISA定量检测hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs输注前后血清炎性和抗炎细胞因子的含量,结果显示输注4周后患者血清炎性细胞因子IL-6、TNFα水平均明显降低(P值均<0.01),从8到12周,其血清中含量持续维持在正常水平;患者血清抗炎细胞因子IL-10、TGFβ在治疗后4周显著上升(P值均<0.01),4周后基本恢复到正常值,到治疗后的12周,其表达水平一直维持在正常值(表 5)。

表 5 hUCB-MNCs联合HUC-MSCs输注前后细胞因子和淋巴细胞亚群变化输注时间 IL-6(ng/L) TNFα(ng/L) IL-10(pg/L) TGFβ(pg/L) CD3+ CD3+CD4+ CD3+CD8+ CD4+CD25+ CD19+ 细胞输注前 198.8±54.01) 300.6±73.51) 18.3±7.81) 25.9±4.31) 75.8±11.01) 23.3±4.21) 48.3±9.31) 1.3±1.21) 32.1±4.21) 输注后(4周) 96.2±19.6 198.9±106.4 48.9±15.7 49.3±7.1 74.8±8.9 53.1±10.9 20.4±6.8 18.3±9.5 12.7±3.6 输注后(8周) 58.9±16.9 92.2±26.1 47.3±8.7 43.9±4.4 76.9±12.4 54.0±7.7 20.4±3.4 18.0±5.0 11.7±5.3 输注后(12周) 59.8±16.4 92.8±13.7 49.6±15.9 35.5±6.4 80.1±10.9 55.9±6.4 16.7±6.0 19.1±8.3 6.1±2.4 F值 49.497 37.071 15.918 35.843 0.493 44.755 52.242 17.337 89.097 P值 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 >0.05 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 注:与输注后的第4、8、12周比较, 1)P<0.05。 采用流式细胞仪分析淋巴细胞亚群比例,细胞输注对CD3+T淋巴细胞无明显影响,输注4周后CD3+CD4+T淋巴细胞和CD4+CD25+Treg显著升高(P值均<0.01);而对CD3+CD8+T淋巴细胞和CD19+B淋巴细胞具有较明显的抑制作用,此状态一直维持至12周(表 5)。

3. 讨论

我国HBV感染率高,最终导致肝硬化、肝功能失代偿、门静脉高压、肝硬化,甚至肝癌等,死亡率呈逐年上升的趋势。内蒙古地区是少数民族聚集地,人群感染HBV发生率更高[16]。加之内蒙古地区冬天比较寒冷和传统习惯,多数男性喜欢饮酒,更加重了肝细胞的损伤,加速了肝硬化、门静脉高压以及肝癌的发生,因此很多患者在感染肝炎病毒后,发生肝硬化失代偿的年龄相对较轻,大多数在60岁之前,而且以男性居多。

肝功能失代偿并发肝硬化时,多数患者一般状况较差,免疫功能低,易并发感染,特别是肠道感染,再加肝功能失代偿年久,多数患者伴有腹水。所以应用干细胞治疗此类患者前需要评估患者整体状况,本临床研究参与的患者,Child-Pugh分级多在B级和C级。

由于输注细胞需要反复多次操作,而且肝硬化患者凝血功能差,为了尽量减少对患者的创伤,本研究未采用肝动脉介入注射技术,而是应用多次静脉回输的方法,更简便、安全。

在输注细胞前,除了对患者整体状态进行评估外,还应用流式细胞检测患者的免疫状态。多数肝硬化患者的免疫功能普遍较低,特别是辅助性T淋巴细胞(CD3+CD4+),明显低于正常参考值,因此在hUC-MSCs治疗前必须调整患者一般状况,提高其免疫功能。笔者团队前期临床研究[6]发现,hUCB-MNCs具有良好的提高患者免疫的功效,本研究与患者及其家属沟通,经患者本人及家属同意,先输注hUCB-MNCs,以便先改善患者整体状况,提高其免疫功能。临床观察发现部分患者在输注hUCB-MNCs后,甚至在1周之内,全身不适、食欲、精神状况明显改善,流式细胞分析静脉血中辅助性T淋巴细胞有所上升,此效果与笔者团队前期研究[6]结果相同,说明hUCB-MNCs也可以改善肝硬化患者的一般状况和免疫功能。

研究提示hUC-MSCs能够向多方向分化,如神经、骨骼、肌肉、心肌、肝细胞等[17],同时具有强大的修复功能[18]。已知肝细胞感染HBV感染后,肝细胞损伤、坏死,释放大量的肝细胞酶,经常规治疗后门静脉压降低,腹水形成也相应减少,但是胃肠道的有毒物质未经肝脏处理,直接进入体循环,部分患者血氨明显升高。而hUC-MSCs输入后,可以归巢到肝脏,分化为肝细胞或进入肝脏后修复受损的肝细胞,血液内的有毒物质可以被代谢并排除体外,从而起到治疗肝硬化的作用,本研究结果证实,hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs联合输入4周后,部分患者的血氨下降,肝硬化症状逐步得以控制;除此之外,hUC-MSCs还可以分化为神经细胞,同时具有强大的修复神经细胞损伤的功能[19-20],所以hUC-MSCs输入后肝硬化患者精神、神经状态不佳的情况相应减轻,笔者推断可能与此也有一定的关系,有待进一步验证。

由于肝细胞受损,静脉血中肝细胞酶类升高、胆红素释放增加、合成Alb功能降低,输注hUC-MSCs归巢到肝脏,受微环境的影响分化为肝细胞,同时发挥hUC-MSCs的修复功能,使损伤的肝细胞得以恢复,酶释放减少,凝血酶原和Alb合成增加,腹水减轻,患者的一般临床症状改善, Child-Pugh评分随之降低, 而Child-Pugh评分又可预测失代偿期肝硬化患者的短期预后,对选择适当的临床治疗方案有一定指导作用[21]。研究发现细胞治疗对于门静脉高压导致的腹水疗效较差,如本研究的No.10患者腹水减轻并不明显。

众所周知,HBV感染后,肝细胞及其周围组织同时发生持续和反复慢性炎症反应,由于参与炎性反应的细胞主要是CD3+CD8+T淋巴细胞和产生抗体的CD19+B淋巴细胞,此类细胞在肝内的聚集,释放大量的炎性细胞因子,刺激肝内纤维细胞过度增生,导致肝硬化,同时释放的炎性细胞因子和抗体也可以进一步杀伤和破坏肝细胞。已知hUC-MSCs本身及其释放的外泌体具有强大的免疫调节功能[22-23],可以抑制过度活跃、聚集于肝内的炎性细胞。本研究中心经长期的临床试验发现,hUC-MSCs输注后,随着时间的延长,炎性细胞及其炎性因子,如IL-6、TNFα逐渐降低[24]。而CD4+CD25+Treg逐渐上升,说明输注hUC-MSCs可上调肝硬化患者CD4+CD25+ Treg水平,这一结果与文献研究结果[25-26]相吻合;抗炎细胞因子IL-10、TGFβ逐渐上升,抑制了炎性反应的进一步加重,防止肝细胞持续损伤、坏死,同时间接地调控肝组织的进一步纤维化[24]。提示hUCB-MNCs联合hUC-MSCs治疗可通过影响机体的免疫状况来调节免疫性疾病的转归,可能产生的副作用目前还在随访观察中。截至目前,11例入组治疗患者均未发现明显的不良反应。这些研究结果为hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs联合疗法可以优化肝功能且抑制病情发展提供了有力的依据。

hUCB-MNCs和hUC-MSCs联合输注可以分化为肝细胞或进入肝脏后修复受损的肝细胞,抑制炎性因子释放,上调Treg水平,从而调节肝硬化患者免疫功能,改善患者一般状态。针对检测指标的改变,对其治疗肝硬化的免疫调节机制进行评价,为终末期肝病的治疗探索新方法。

-

[1] General Office of National Health Commission. Standard for diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer (2022 edition)[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2022, 38(5): 1006-1030. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.05.007.国家卫生健康委办公厅. 胰腺癌诊疗指南(2022年版)[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2022, 38(5): 1006-1030. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2022.05.007. [2] BRAY F, FERLAY J, SOERJOMATARAM I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21492. [3] SIEGEL RL, MILLER KD, JEMAL A. Cancer statistics, 2020[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2020, 70(1): 7-30. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21590. [4] TANG D, WU Q, ZHANG J, et al. Galectin-1 expression in activated pancreatic satellite cells promotes fibrosis in chronic pancreatitis/pancreatic cancer via the TGF-β1/Smad pathway[J]. Oncol Rep, 2018, 39(3): 1347-1355. DOI: 10.3892/or.2018.6202. [5] KAJDANIUK D, MAREK B, BORGIEL-MAREK H, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) in physiology and pathology[J]. Endokrynol Pol, 2013, 64(5): 384-396. DOI: 10.5603/EP.2013.0022. [6] KUMARI A, SHONIBARE Z, MONAVARIAN M, et al. TGFβ signaling networks in ovarian cancer progression and plasticity[J]. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2021, 38(2): 139-161. DOI: 10.1007/s10585-021-10077-z. [7] GALLO-OLLER G, DI SCALA M, ARANDA F, et al. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) activity in immuno-oncology studies[J]. Methods Enzymol, 2020, 636: 129-172. DOI: 10.1016/bs.mie.2019.06.008. [8] ZHAO Y, QIAO W, WANG X, et al. 14-3-3ζ/TGFβR1 promotes tumor metastasis in lung squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(50): 82972-82984. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.12690. [9] FAN JY, WANG J. Expression of Mir-196b and TGFβR1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its significance[J]. Shandong Med J, 2021, 61(10): 53-56. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.范婧怡, 王健. 胰腺导管腺癌组织miR-196b、TGFβR1表达变化及其意义[J]. 山东医药, 2021, 61(10): 53-56. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X. [10] PRINCIPE DR, DOLL JA, BAUER J, et al. TGF-β: duality of function between tumor prevention and carcinogenesis[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014, 106(2): djt369. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djt369. [11] WEISS A, ATTISANO L. The TGFbeta superfamily signaling pathway[J]. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, 2013, 2(1): 47-63. DOI: 10.1002/wdev.86. [12] JIA EC, ZHU WL. Research progress of transforming growth factor β Ⅱ receptor in digestive system tumors. [J]. Chongqing Med J, 2016, 45(23): 3293-3295, 3299. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2016.23.046.贾恩朝, 朱武凌. 转化生长因子β Ⅱ型受体在消化系统肿瘤中的研究进展[J]. 重庆医学, 2016, 45(23): 3293-3295, 3299. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2016.23.046. [13] GUO W, DONG Z, GUO Y, et al. Association of polymorphisms in transforming growth factor-β receptors with susceptibility to gastric cardia adenocarcinoma[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2012, 39(4): 4301-4309. DOI: 10.1007/s11033-011-1217-0. [14] BIANKIN AV, WADDELL N, KASSAHN KS, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes[J]. Nature, 2012, 491(7424): 399-405. DOI: 10.1038/nature11547. [15] CHEN YN, ZHANG XY. Research progress on the role of transforming growth factor β Ⅲ receptor in the development of human tumors[J]. J Modern Oncol, 2022, 30(10): 1907-1910. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4992.陈亚楠, 张学彦. 转化生长因子βⅢ型受体在人类肿瘤发生发展中作用的研究进展[J]. 现代肿瘤医学, 2022, 30(10): 1907-1910. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4992. [16] TZAVLAKI K, MOUSTAKAS A. TGF-β Signaling[J]. Biomolecules, 2020, 10(3). DOI: 10.3390/biom10030487. [17] YIN Z, MA T, HUANG B, et al. Macrophage-derived exosomal microRNA-501-3p promotes progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through the TGFBR3-mediated TGF-β signaling pathway[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 38(1): 310. DOI: 10.1186/s13046-019-1313-x. [18] ZOU ML, CHEN ZH, TENG YY, et al. The Smad dependent TGF-β and BMP signaling pathway in bone remodeling and therapies[J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2021, 8: 593310. DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.593310. [19] MARTIN-MALPARTIDA P, BATET M, KACZMARSKA Z, et al. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors[J]. Nat Commun, 2017, 8(1): 2070. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02054-6. [20] PRINCIPE DR, DECANT B, MASCARIÑAS E, et al. TGFβ signaling in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment promotes fibrosis and immune evasion to facilitate tumorigenesis[J]. Cancer Res, 2016, 76(9): 2525-2539. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1293. [21] WANG F, XIA X, YANG C, et al. SMAD4 gene mutation renders pancreatic cancer resistance to radiotherapy through promotion of autophagy[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(13): 3176-3185. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3435. [22] SHUGANG X, HONGFA Y, JIANPENG L, et al. Prognostic value of SMAD4 in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis[J]. Transl Oncol, 2016, 9(1): 1-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.11.007. [23] DU Y, ZHOU X, HUANG Z, et al. Meta-analysis of the prognostic value of smad4 immunohistochemistry in various cancers[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10): e110182. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110182. [24] WANG JD, JIN K, CHEN XY, et al. Clinicopathological significance of SMAD4 loss in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(10): 16704-16711. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.14335. [25] KANG Y, LING J, SUZUKI R, et al. SMAD4 regulates cell motility through transcription of N-cadherin in human pancreatic ductal epithelium[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(9): e107948. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107948. [26] LEUNG L, RADULOVICH N, ZHU CQ, et al. Loss of canonical Smad4 signaling promotes KRAS driven malignant transformation of human pancreatic duct epithelial cells and metastasis[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(12): e84366. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084366. [27] LI Y, BASTI A, YALÇIN M, et al. Circadian dysregulation of the TGFβ/SMAD4 pathway modulates metastatic properties and cell fate decisions in pancreatic cancer cells[J]. iScience, 2020, 23(10): 101551. DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101551. [28] DARDARE J, WITZ A, MERLIN JL, et al. SMAD4 and the TGFβ pathway in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(10). DOI: 10.3390/ijms21103534. [29] NEUZILLET C, HAMMEL P, TIJERAS-RABALLAND A, et al. Targeting the Ras-ERK pathway in pancreatic adenocarcinoma[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2013, 32(1-2): 147-162. DOI: 10.1007/s10555-012-9396-2. [30] BUONATO JM, LAZZARA MJ. ERK1/2 blockade prevents epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells and promotes their sensitivity to EGFR inhibition[J]. Cancer Res, 2014, 74(1): 309-319. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4721. [31] PRINCIPE DR, DIAZ AM, TORRES C, et al. TGFβ engages MEK/ERK to differentially regulate benign and malignant pancreas cell function[J]. Oncogene, 2017, 36(30): 4336-4348. DOI: 10.1038/onc.2016.500. [32] GUO Q. Changes in mitochondrial function during EMT induced by TGFβ-1 in pancreatic cancer[J]. Oncol Lett, 2017, 13(3): 1575-1580. DOI: 10.3892/ol.2017.5613. [33] CHANG CH, PAUKLIN S. ROS and TGFβ: from pancreatic tumour growth to metastasis[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 40(1): 152. DOI: 10.1186/s13046-021-01960-4. [34] SANJABI S, OH SA, LI MO. Regulation of the immune response by TGF-β: From conception to autoimmunity and infection[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2017, 9(6): a022236. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022236. [35] MA B, LI JG, WANG J, et al. Promotion effect of miR-106b on invasion and migration of colon cancer cells through targeting TGF-β/Smad pathway[J]. J Jilin Univ(Med Edit), 2021, 47(3): 636-636. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587Ⅹ.20210312.马博, 李建刚, 王俊, 等. miR-106b靶向调控TGF-β/Smad通路对结肠癌细胞侵袭和迁移的促进作用[J]. 吉林大学学报(医学版), 2021, 47(3): 636-636. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587Ⅹ.20210312. [36] DAVID CJ, MASSAGUÉ J. Contextual determinants of TGFβ action in development, immunity and cancer[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018, 19(7): 419-435. DOI: 10.1038/s41580-018-0007-0. [37] ANDERTON MJ, MELLOR HR, BELL A, et al. Induction of heart valve lesions by small-molecule ALK5 inhibitors[J]. Toxicol Pathol, 2011, 39(6): 916-924. DOI: 10.1177/0192623311416259. [38] MELISI D, GARCIA-CARBONERO R, MACARULLA T, et al. Galunisertib plus gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine for first-line treatment of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer[J]. Br J Cancer, 2018, 119(10): 1208-1214. DOI: 10.1038/s41416-018-0246-z. [39] FAIVRE S, SANTORO A, KELLEY RK, et al. Novel transforming growth factor beta receptor I kinase inhibitor galunisertib (LY2157299) in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Liver Int, 2019, 39(8): 1468-1477. DOI: 10.1111/liv.14113. [40] KOVACS RJ, MALDONADO G, AZARO A, et al. Cardiac safety of TGF-β receptor i kinase inhibitor LY2157299 monohydrate in cancer patients in a First-in-Human dose study[J]. Cardiovasc Toxicol, 2015, 15(4): 309-323. DOI: 10.1007/s12012-014-9297-4. 期刊类型引用(8)

1. 刘晓敏,祁冉,郑玉峰,蒋珍,张腊梅. 影响肝硬化失代偿患者人脐带间充质干细胞治疗效果的影响因素探究. 罕少疾病杂志. 2024(04): 48-50 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 袁雪青,朱梅. 间充质干细胞修复大鼠子宫切口瘢痕缺陷的实验研究. 国际医药卫生导报. 2024(14): 2343-2347 .  百度学术

百度学术3. 汤艳,沈爱春. 恩替卡韦联合复方鳖甲软肝片在慢性乙型肝炎肝硬化患者中的治疗效果. 中国医学创新. 2024(29): 64-68 .  百度学术

百度学术4. 陈刚,谷光丽,何映雪,唐尧. 血清表皮生长因子对肝硬化食管胃静脉曲张患者再出血的诊断价值分析. 转化医学杂志. 2024(10): 1698-1702 .  百度学术

百度学术5. 杨明霞. 产前乙肝病毒检查对母婴结局的临床意义分析. 中国现代药物应用. 2023(09): 76-79 .  百度学术

百度学术6. 杨玉伟,李万里,陈继冰,丰丙政,徐之然,吴玲玲,武桢,顾新伟,高宏君. 间充质干细胞包裹人胰岛减轻即刻经血液介导的炎症反应的体外研究. 器官移植. 2023(04): 562-569 .  百度学术

百度学术7. 梅小利,杜伟,吴思澜,杨雪,于冰,李聪,黄崇刚. 人脐带间充质干细胞连续静脉注射对大鼠的安全性及肝脏的影响. 西部医学. 2023(07): 959-963 .  百度学术

百度学术8. 李丹丹,王艳南,王品鸽. 舒肝宁联合富马酸替诺福韦二吡呋酯对慢性乙肝肝硬化患者免疫功能及肝功能的影响. 内蒙古医学杂志. 2022(10): 1177-1180 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(0)

-

PDF下载 ( 2378 KB)

PDF下载 ( 2378 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术