肝纤维化治疗的新视角:靶向巨噬细胞代谢

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.04.027

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:许钧、金卫林参与文章的结构设计;许钧起草文章初稿;李汛、金卫林修改文章关键内容;所有作者阅读并批准最终稿。

A new perspective in the treatment of liver fibrosis: Targeting macrophage metabolism

-

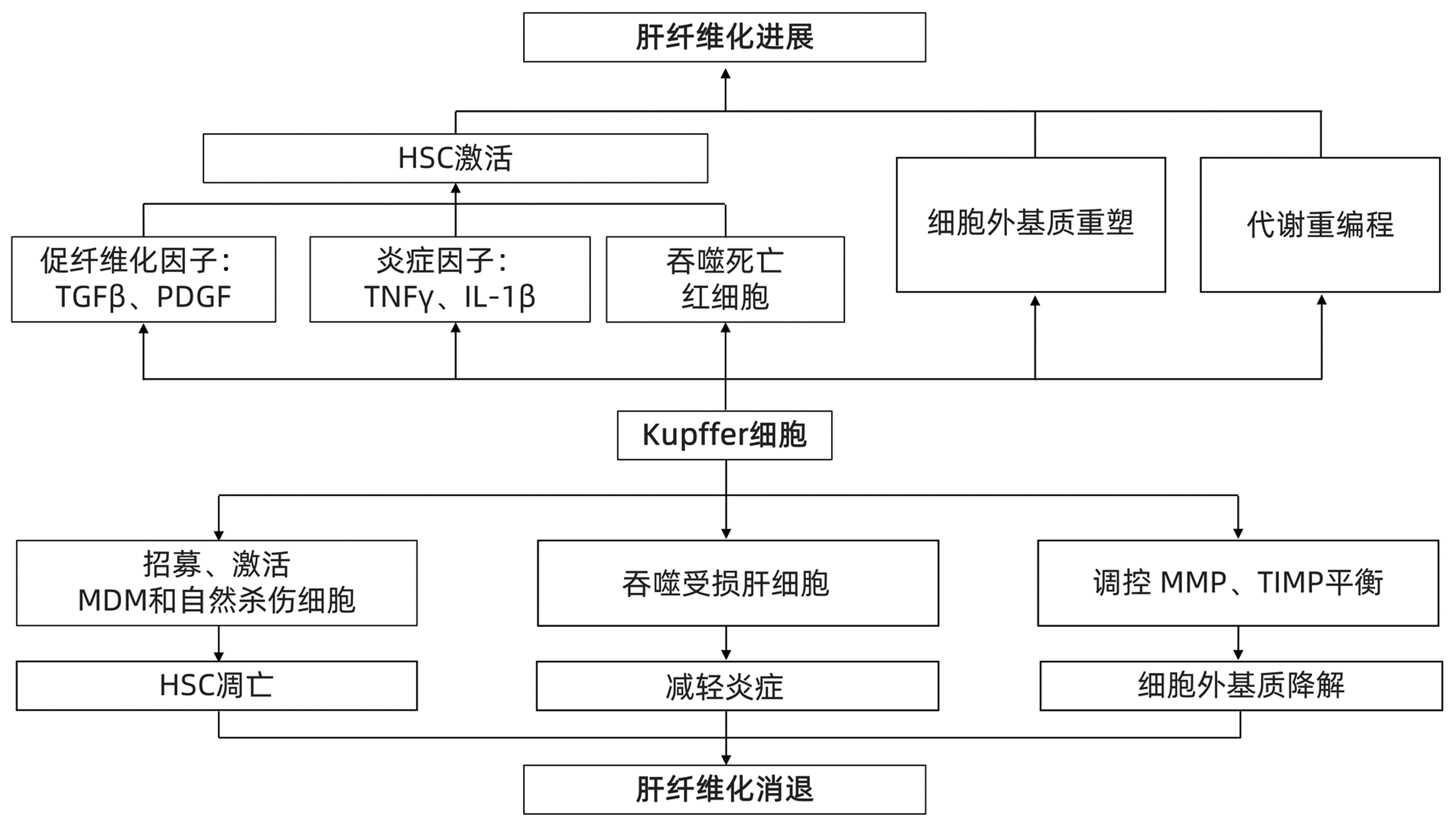

摘要: 肝纤维化是由多种病因引起的细胞外基质过度累积,导致纤维瘢痕形成的病理过程。目前,病因治疗(如有效的抗病毒治疗)仍是肝纤维化的主要治疗策略。肝巨噬细胞作为肝纤维化的核心参与者,影响肝纤维化的进展与消退,被认为是肝纤维化治疗的重要靶点。近年来,随着免疫代谢领域的进展,代谢重编程已成为决定巨噬细胞结局和推动疾病发展的关键因素。本文综述了肝纤维化过程中巨噬细胞的作用及其代谢变化,并讨论靶向巨噬细胞代谢的抗纤维化潜力,为肝纤维化的发生、发展和治疗提供新的思路Abstract: Liver fibrosis is a pathological process of fibrous scar formation caused by excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix due to various etiologies. At present, etiological treatment, such as effective antiviral therapy, is still the main treatment strategy for liver fibrosis. As the core participant of liver fibrosis, liver macrophages affect the progression and regression of liver fibrosis and are thus considered an important target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. With the recent advances in the field of immune metabolism, metabolic reprogramming has become a key factor for determining the outcome of macrophages and promoting the development of diseases. This article reviews the role and metabolic changes of macrophages during liver fibrosis and discusses the anti-fibrotic potential of targeting macrophage metabolism, so as to provide new ideas for the development, progression, and treatment of liver fibrosis.

-

Key words:

- Liver Cirrhosis /

- Macrophages /

- Therapeutics

-

[1] ROEHLEN N, CROUCHET E, BAUMERT TF. Liver fibrosis: Mechanistic concepts and therapeutic perspectives[J]. Cells, 2020, 9(4): 875. DOI: 10.3390/cells9040875. [2] PHAN AT, GOLDRATH AW, GLASS CK. Metabolic and epigenetic coordination of T cell and macrophage immunity[J]. Immunity, 2017, 46(5): 714-729. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.016. [3] O'NEILL LA, KISHTON RJ, RATHMELL J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2016, 16(9): 553-565. DOI: 10.1038/nri.2016.70. [4] van DER HEIDE D, WEISKIRCHEN R, BANSAL R. Therapeutic targeting of hepatic macrophages for the treatment of liver diseases[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 2852. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02852. [5] LI P, HE K, LI J, et al. The role of Kupffer cells in hepatic diseases[J]. Mol Immunol, 2017, 85: 222-229. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.02.018. [6] GUILLOT A, TACKE F. Liver macrophages: Old dogmas and new insights[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2019, 3(6): 730-743. DOI: 10.1002/hep4.1356. [7] WANG C, MA C, GONG L, et al. Macrophage polarization and its role in liver disease[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 803037. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.803037. [8] TACKE F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases[J]. J Hepatol, 2017, 66(6): 1300-1312. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.026. [9] YUNNA C, MENGRU H, LEI W, et al. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2020, 877: 173090. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173090. [10] WU K, MA J, ZHAN Y, et al. Down-regulation of microRNA-214 contributed to the enhanced mitochondrial transcription factor A and inhibited proliferation of colorectal cancer cells[J]. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2018, 49(2): 545-554. DOI: 10.1159/000492992. [11] GONG J, LI J, DONG H, et al. Inhibitory effects of berberine on proinflammatory M1 macrophage polarization through interfering with the interaction between TLR4 and MyD88[J]. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2019, 19(1): 314. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-019-2710-6. [12] WANG F, ZHANG S, JEON R, et al. Interferon gamma induces reversible metabolic reprogramming of M1 macrophages to sustain cell viability and pro-inflammatory activity[J]. EBioMedicine, 2018, 30: 303-316. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.009. [13] SINGLA RD, WANG J, SINGLA DK. Regulation of Notch 1 signaling in THP-1 cells enhances M2 macrophage differentiation[J]. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2014, 307(11): H1634-H1642. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00896.2013. [14] WEI W, LI ZP, BIAN ZX, et al. Astragalus polysaccharide RAP induces macrophage phenotype polarization to M1 via the Notch signaling pathway[J]. Molecules, 2019, 24(10): 2016. DOI: 10.3390/molecules24102016. [15] SHENG J, ZHANG B, CHEN Y, et al. Capsaicin attenuates liver fibrosis by targeting Notch signaling to inhibit TNF-α secretion from M1 macrophages[J]. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol, 2020, 42(6): 556-563. DOI: 10.1080/08923973.2020.1811308. [16] SHAPOURI-MOGHADDAM A, MOHAMMADIAN S, VAZINI H, et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2018, 233(9): 6425-6440. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.26429. [17] GAO S, ZHOU J, LIU N, et al. Curcumin induces M2 macrophage polarization by secretion IL-4 and/or IL-13[J]. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2015, 85: 131-139. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.025. [18] LU H, WU L, LIU L, et al. Quercetin ameliorates kidney injury and fibrosis by modulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2018, 154: 203-212. DOI: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.05.007. [19] DOU L, SHI X, HE X, et al. Macrophage phenotype and function in liver disorder[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 3112. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03112. [20] CHENG D, CHAI J, WANG H, et al. Hepatic macrophages: Key players in the development and progression of liver fibrosis[J]. Liver Int, 2021, 41(10): 2279-2294. DOI: 10.1111/liv.14940. [21] SCHWABE RF, TABAS I, PAJVANI UB. Mechanisms of fibrosis development in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158(7): 1913-1928. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.311. [22] TSUCHIDA T, FRIEDMAN SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 14(7): 397-411. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38. [23] ROBERT S, GICQUEL T, VICTONI T, et al. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and inflammasome pathway in molecular mechanisms of fibrosis[J]. Biosci Rep, 2016, 36(4): e00360. DOI: 10.1042/BSR20160107. [24] MEHTA KJ, FARNAUD SJ, SHARP PA. Iron and liver fibrosis: Mechanistic and clinical aspects[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2019, 25(5): 521-538. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i5.521. [25] ROTH KJ, COPPLE BL. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors in the development of liver fibrosis[J]. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 1(6): 589-597. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.09.005. [26] LIASKOU E, ZIMMERMANN HW, LI KK, et al. Monocyte subsets in human liver disease show distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 57(1): 385-398. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26016. [27] KISSELEVA T, BRENNER D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 18(3): 151-166. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-020-00372-7. [28] TACKE F, ZIMMERMANN HW. Macrophage heterogeneity in liver injury and fibrosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2014, 60(5): 1090-1096. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.025. [29] FENG M, DING J, WANG M, et al. Kupffer-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 contributes to liver fibrosis resolution[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2018, 14(9): 1033-1040. DOI: 10.7150/ijbs.25589. [30] YU B, QIN SY, HU BL, et al. Resveratrol improves CCL4-induced liver fibrosis in mouse by upregulating endogenous IL-10 to reprogramme macrophages phenotype from M(LPS) to M(IL-4)[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2019, 117: 109110. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109110. [31] VAN DEN BOSSCHE J, O'NEILL LA, MENON D. Macrophage immunometabolism: Where are we (going)?[J]. Trends Immunol, 2017, 38(6): 395-406. DOI: 10.1016/j.it.2017.03.001. [32] CASTEGNA A, GISSI R, MENGA A, et al. Pharmacological targets of metabolism in disease: Opportunities from macrophages[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2020, 210: 107521. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107521. [33] FERNÁNDEZ-VELEDO S, CEPERUELO-MALLAFRÉ V, VENDRELL J. Rethinking succinate: an unexpected hormone-like metabolite in energy homeostasis[J]. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2021, 32(9): 680-692. DOI: 10.1016/j.tem.2021.06.003. [34] BIEGHS V, WALENBERGH SM, HENDRIKX T, et al. Trapping of oxidized LDL in lysosomes of Kupffer cells is a trigger for hepatic inflammation[J]. Liver Int, 2013, 33(7): 1056-1061. DOI: 10.1111/liv.12170. [35] BIEGHS V, WOUTERS K, VAN GORP PJ, et al. Role of scavenger receptor A and CD36 in diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in hyperlipidemic mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 138(7): 2477-2486. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.051. [36] LEROUX A, FERRERE G, GODIE V, et al. Toxic lipids stored by Kupffer cells correlates with their pro-inflammatory phenotype at an early stage of steatohepatitis[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 57(1): 141-149. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.028. [37] KANAMORI Y, TANAKA M, ITOH M, et al. Iron-rich Kupffer cells exhibit phenotypic changes during the development of liver fibrosis in NASH[J]. iScience, 2021, 24(2): 102032. DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.102032. [38] HANDA P, THOMAS S, MORGAN-STEVENSON V, et al. Iron alters macrophage polarization status and leads to steatohepatitis and fibrogenesis[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2019, 105(5): 1015-1026. DOI: 10.1002/JLB.3A0318-108R. [39] LESLIE J, MACIA MG, LULI S, et al. c-Rel orchestrates energy-dependent epithelial and macrophage reprogramming in fibrosis[J]. Nat Metab, 2020, 2(11): 1350-1367. DOI: 10.1038/s42255-020-00306-2. [40] XU F, GUO M, HUANG W, et al. Annexin A5 regulates hepatic macrophage polarization via directly targeting PKM2 and ameliorates NASH[J]. Redox Biol, 2020, 36: 101634. DOI: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101634. [41] GAO YS, QIAN MY, WEI QQ, et al. WZ66, a novel acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor, alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in mice[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2020, 41(3): 336-347. DOI: 10.1038/s41401-019-0310-0. [42] WENG SY, SCHUPPAN D. AMPK regulates macrophage polarization in adipose tissue inflammation and NASH[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 58(3): 619-621. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.031. [43] LOOMBA R, KAYALI Z, NOUREDDIN M, et al. GS-0976 reduces hepatic steatosis and fibrosis markers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 2018, 155(5): 1463-1473. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.027. [44] FRANCQUE S, SZABO G, ABDELMALEK MF, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 18(1): 24-39. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-020-00366-5. [45] ORFILA C, LEPERT JC, ALRIC L, et al. Immunohistochemical distribution of activated nuclear factor kappaB and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carbon tetrachloride-induced chronic liver injury in rats[J]. Histochem Cell Biol, 2005, 123(6): 585-593. DOI: 10.1007/s00418-005-0785-2. [46] STIENSTRA R, MANDARD S, TAN NS, et al. The Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is a direct target gene of PPARalpha in liver[J]. J Hepatol, 2007, 46(5): 869-877. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.11.019. [47] IP E, FARRELL G, HALL P, et al. Administration of the potent PPARalpha agonist, Wy-14, 643, reverses nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice[J]. Hepatology, 2004, 39(5): 1286-1296. DOI: 10.1002/hep.20170. [48] GILGENKRANTZ H, MALLAT A, MOREAU R, et al. Targeting cell-intrinsic metabolism for antifibrotic therapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 74(6): 1442-1454. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.02.012. [49] GALLI A, CRABB DW, CENI E, et al. Antidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit collagen synthesis and hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo and in vitro[J]. Gastroenterology, 2002, 122(7): 1924-1940. DOI: 10.1053/gast.2002.33666. [50] RATZIU V, CHARLOTTE F, BERNHARDT C, et al. Long-term efficacy of rosiglitazone in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of the fatty liver improvement by rosiglitazone therapy (FLIRT 2) extension trial[J]. Hepatology, 2010, 51(2): 445-453. DOI: 10.1002/hep.23270. [51] MCMAHAN RH, WANG XX, CHENG LL, et al. Bile acid receptor activation modulates hepatic monocyte activity and improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. J Biol Chem, 2013, 288(17): 11761-11770. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446575. [52] YOUNOSSI ZM, RATZIU V, LOOMBA R, et al. Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10215): 2184-2196. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33041-7. -

PDF下载 ( 2010 KB)

PDF下载 ( 2010 KB)

下载:

下载: