慢性乙型肝炎患者发生肝细胞癌的危险因素分析

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2021.07.022

Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B

-

摘要:

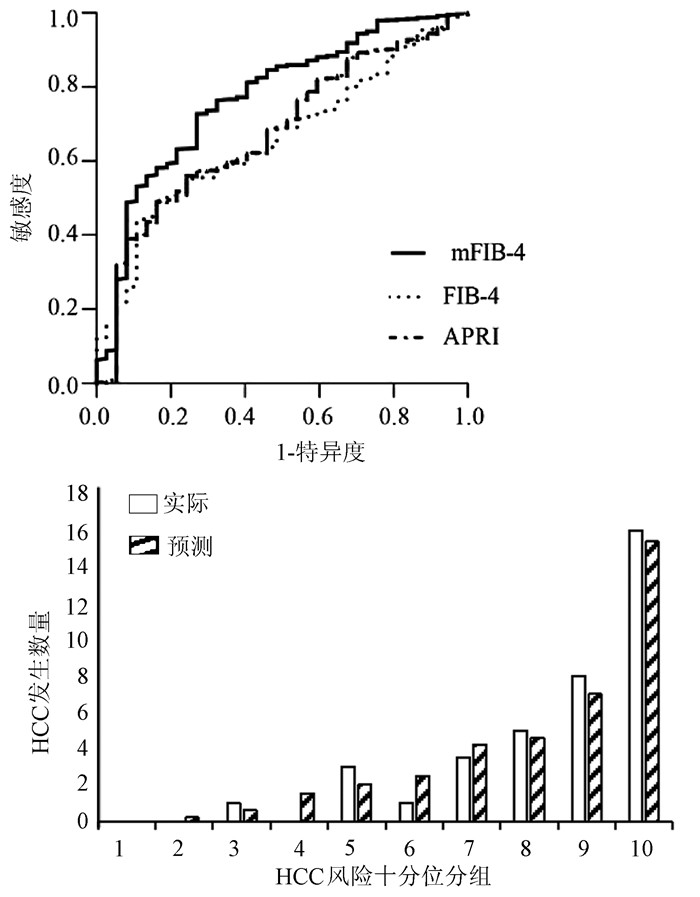

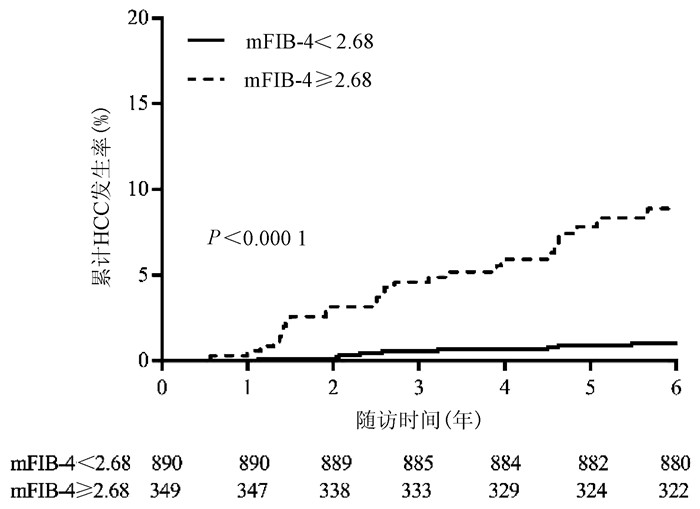

目的 探究慢性乙型肝炎(CHB)患者发生肝细胞癌(HCC)的危险因素。 方法 收集2013年1月—2015年6月北京地坛医院确诊的CHB且随访超过3年的患者,共1239例。其中非肝硬化患者1108例,肝硬化患者131例。收集患者的一般资料及实验室检查指标并计算APRI、FIB-4及mFZB-4评分。符合正态分布的计量资料2组间比较采用t检验;非正态分布的计量资料2组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。计数资料2组间比较采用χ2检验。影响HCC发生的独立危险因素采用Cox回归分析。采用受试者工作特征曲线下面积(AUC)比较3种评分对CHB患者发生HCC的预测能力,采用DeLong检验对各个评分的AUC进行比较。通过拟合优度检验分析mFIB-4评分校准能力。使用Kalplan-Merier法对HCC发生进行分析,log-rank法进行比较。 结果 中位随访时间为4.6年,37例(3.0%)患者发生HCC。多因素Cox回归分析显示,年龄(HR=1.046,95%CI:1.018~1.074,P=0.001)、ALT (HR=0.995,95%CI:0.992~0.999,P=0.008)、AST (HR=0.994,95%CI:0.990~0.998,P=0.020)和PLT (HR=0.988,95%CI:0.981~0.994,P=0.001)是影响HCC发生的独立危险因素。mFIB-4、FIB-4、APRI评分的AUC分别为0.771、0.658、0.676,其中mFIB-4评分的AUC大于FIB-4评分(Z=5.629, P<0.000 1)及APRI评分(Z=4.243, P<0.000 1)。与mFIB-4<2.68的患者相比,mFIB-4 ≥2.68的患者HCC发生风险更高(Z=37.840, P<0.000 1)。 结论 年龄、ALT、AST和PLT是CHB患者发生HCC的独立危险因素。与FIB-4,APRI评分相比,mFIB-4评分对CHB患者发生HCC的预测价值更高。mFIB-4 ≥2.68的CHB患者是发生HCC的高危人群。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Methods A total of 1239 patients who were diagnosed with CHB in Beijing Ditan Hospital from January 2013 to June 2015 and were followed up for more than 3 years were enrolled, among whom 1108 had no liver cirrhosis and 131 had liver cirrhosis. General information and laboratory markers were collected. The chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data between groups, and the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of continuous data between groups. The t-test was used for comparison of normally distributed continuous data between two groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed continuous data between two groups; the chi-square test for comparison of categorical data between two groups. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to identify the independent risk factors for HCC. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used to compare the ability of fibrosis-4 (FIB-4), modified FIB-4 (mFIB-4), and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) scores to predict the development of HCC, and the DeLong test was used for comparison of AUC. Goodness of fit was used to evaluate the calibration ability of mFIB-4 score. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze the development of HCC, and the log-rank test was used for comparison. Results The median follow-up time was 4.6 years, and of all patients, 37 (3.0%) developed HCC. The multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that age (hazard ratio [HR]=1.046, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.018-1.074, P=0.001), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (HR=0.995, 95%CI: 0.992-0.999, P=0.008), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (HR=0.994, 95%CI: 0.990-0.998, P=0.020), and platelet count (PLT) (HR=0.988, 95%CI: 0.981-0.994, P=0.001) were independent risk factors for HCC in CHB patients. The mFIB-4, FIB-4, and APRI scores had an AUC of 0.771, 0.658, and 0.676, respectively, and mFIB-4 score had a significantly higher AUC than FIB-4 score (Z=5.629, P < 0.000 1) and APRI score (Z=4.243, P < 0.000 1). Compared with the patients with mFIB-4 < 2.68, the patients with mFIB-4 ≥2.68 had a significantly higher risk of HCC (Z=37.840, P < 0.000 1). Conclusion Age, ALT, AST, and PLT are independent risk factors for HCC in CHB patients. Compared with FIB-4 and APRI scores, mFIB-4 s core has a higher value in predicting HCC in CHB patients. The patients with mFIB-4 ≥2.68 are the high-risk population of HCC. -

Key words:

- Chronic Hepatitis B /

- Carcinoma, Hepatocellular /

- Risk Factors /

- Liver Fibrosis Score

-

慢性乙型肝炎(CHB)相关的慢加急性肝衰竭(acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure,ACHBLF)是在慢性HBV感染引起的CHB基础上出现的急性严重肝功能障碍临床综合征,病死率极高。因我国慢性HBV的高感染率,ACHBLF已成为影响患者生存质量的重要因素[1]。在CHB向ACHBLF进展过程中,存在着患者肝功能急剧恶化,但尚未达到肝衰竭的“肝衰竭前期(pre-ACHBLF)”阶段[2],如能在此阶段进行预警及干预,则有可能预防进一步发展为肝衰竭。

目前普遍认为细胞免疫功能紊乱是ACHBLF发生的病理机制之一,许多免疫细胞如髓系抑制性细胞(myeloid-derived suppressor cells, MDSC)、调节性T淋巴细胞(Treg)、分泌IL-17的CD4 T淋巴细胞(IL-17-producing CD4 T cells,Th17)和细胞毒性T淋巴细胞等在肝衰竭的发病中发挥重要作用[3-5]。尽管既往许多研究已证实肝衰竭发病与免疫密切相关,但pre-ACHBLF阶段的免疫状态及其与疾病进展的关系尚不清楚,因此本研究探讨了MDSC、Th17、Treg和分泌IL-17的CD8 T淋巴细胞(IL-17-producing CD8 T cells, Tc17)在pre-ACHBLF和ACHBLF患者中的表达,以期为ACHBLF的早期治疗提供思路。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

选取2018年8月—2019年5月于石家庄市第五医院住院患者45例,其中ACHBLF患者、pre-ACHBLF患者和CHB患者各15例,同时选取于本院健康体检者15例作为健康对照组(HC组)。ACHBLF和pre-ACHBLF的临床诊断均符合《肝衰竭诊治指南(2018年版)》[6];CHB的临床诊断符合《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2015年版)》[7]。排除标准为合并其他病毒性肝炎或由酒精、药物等原因导致的肝脏疾病;肝癌或其他恶性肿瘤伴有肝脏转移;患有自身免疫性疾病、HIV感染、妊娠或有严重的心、肺、肾脏、神经系统等疾病。

1.2 标本采集与储存

采用EDTA-K2抗凝的真空采血管于清晨空腹采集外周静脉血约3 mL,取100 μL用于流式细胞仪检测外周血MDSC频数,剩余全血分离外周血单个核细胞(peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMC)。所有标本均为新鲜抗凝血,且在采集后4 h内处理。

1.3 流式细胞仪检测外周血免疫细胞的水平

MDSC细胞检测:取100 μL全血加至流式管中,然后分别加入CD11b-APC、CD33-PE和HLA-DR-PE/Cy7流式抗体各2 μL,避光孵育15 min后,每管加入溶血素500 μL,室温避光静置15 min,离心洗涤,加入流式鞘液300 μL重悬细胞,流式细胞仪检测MDSC细胞比例。

Treg细胞检测:收集PBMC,加入CD4-FITC和CD25-APC抗体各2 μL,4 ℃避光孵育30 min。经固定破膜处理后,离心洗涤2次,重悬细胞,然后加入10 μL Foxp3-PE抗体,4 ℃避光孵育45 min,离心洗涤,加入流式鞘液200 μL重悬细胞,流式细胞仪检测。

Th17、Tc17细胞检测:收集PBMC,用佛波醇酯和离子霉素刺激,同时加入GolgiStop,4 h后收集细胞至流式管,加入CD4-FITC和CD8a-PerCP/Cy5.5抗体各2 μL,4 ℃避光孵育30 min。经固定破膜处理后,离心洗涤2次,然后加入10 μL IL-17-APC抗体,避光孵育30 min,离心洗涤,加入流式鞘液200 μL重悬细胞,流式细胞仪检测。

1.4 临床检验指标的测定

肝功能检测采用美国雅培公司C8000型生化分析仪,HBeAg检测采用瑞士罗氏公司全自动Cobase601型电化学发光免疫分析仪,血常规检测采用日本希森美康公司XN1000血液分析仪,并计算炎症指标,包括中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞比值(neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NLR)、单核细胞/淋巴细胞比值(monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, MLR)、血小板/淋巴细胞比值(platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR)与全身免疫炎症指数(systemic immune inflammation index,SIRS),SIRS=中性粒细胞×血小板/淋巴细胞。

1.5 统计学方法

采用SPSS 21.0统计软件进行数据分析。符合正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,多组间比较采用独立样本方差分析,组间进一步两两比较采用LSD-t检验;不服从正态分布的计量资料以M(P25~P75)表示,多组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis H检验,进一步两两比较采用Nemenyi检验。变量间的相关性采用Pearson线性相关或Spearman秩相关分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 一般资料

四组间年龄与性别构成具有可比性,差异均无统计学意义(P值均>0.05)。ACHBLF组、pre-ACHBLF组和CHB组患者ALT与AST水平、HBeAg阳性比均明显高于HC组(P值均<0.05)。ACHBLF组和pre-ACHBLF组患者TBil水平均明显高于HC组(P值均<0.05)。ACHBLF组和pre-ACHBLF组患者PTA水平均明显低于CHB组(P值均<0.05)(表 1)。

表 1 四组研究对象一般特征比较Table 1. Comparison of general characteristics of four groups组别 例数 年龄(岁) 性别(男/女,例) ALT(U/L) AST(U/L) HBeAg (+/-) TBil(μmol/L) PTA(%) ACHBLF组 15 45.00±10.86 11/4 67.00(33.00~132.00)1) 88.00(57.70~117.00)1) 10/51) 279.00(241.00~337.00)1) 38.00(25.00~65.50)2) pre-ACHBLF组 15 48.50±7.47 11/4 57.40(31.20~114.00)1) 54.90(34.00~112.00)1) 10/51) 76.40(54.70~129.00)1) 43.90(37.50~51.00)2) CHB组 15 43.10±11.72 12/3 57.00(44.00~261.00)1) 46.00(29.00~135.00)1) 12/31) 20.00(12.00~33.00)1) 84.00(70.50~91.20) HC组 15 42.10±6.37 12/3 21.10(11.00~32.30) 21.70(17.20~27.90) 0/15 11.60(9.90~14.40) - 统计值 F=1.326 χ2=0.373 F=18.594 F=27.525 χ2=23.571 F=48.781 F=26.217 P值 0.275 0.946 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 注:与HC组比较,1)P<0.05;与CHB组比较,2)P<0.05。 2.2 MDSC、Th17、Treg和Tc17细胞的表达

MDSC、Th17、Treg和Tc17细胞水平在四组间差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.01)。与CHB组比较,ACHBLF和pre- ACHBLF组的Th17、Treg和Tc17细胞水平均明显升高(P值均<0.05),同时pre-ACHBLF患者的MDSC细胞水平明显升高,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)(图 1)。

2.3 pre-ACHBLF患者中免疫细胞与炎症指标的关系

相关性分析显示,在pre-ACHBLF患者中,MDSC与白细胞数、中性粒细胞数及NLR、MLR、SIRS呈正相关(P值均<0.05),而Treg细胞仅与白细胞数呈正相关(P=0.043)。相反,Th17/Treg值和Tc17细胞水平与淋巴细胞数呈负相关(P值均<0.05)(表 2)。

表 2 pre-ACHBLF患者免疫细胞水平与炎症指标的关系Table 2. The relationship between the expression of immune cells and the degree of inflammation in patients with pre-ACHBLF炎症指标 MDSC Th17 Treg Th17/Treg Tc17 r值 P值 r值 P值 r值 P值 r值 P值 r值 P值 白细胞 0.775 0.001 0.167 0.668 0.618 0.043 -0.286 0.493 -0.533 0.139 中性粒细胞 0.727 0.002 0.250 0.516 0.491 0.125 -0.238 0.570 -0.417 0.265 淋巴细胞 0.079 0.781 -0.611 0.081 0.333 0.318 -0.790 0.020 -0.795 0.010 NLR 0.571 0.026 0.483 0.187 0.255 0.450 0.048 0.911 -0.150 0.700 MLR 0.786 0.001 0.233 0.546 0.236 0.484 0.024 0.955 -0.433 0.244 PLR 0.161 0.567 0.600 0.088 0.018 0.958 0.429 0.289 0.106 0.787 SIRS 0.846 <0.001 0.233 0.546 0.336 0.312 0.024 0.955 -0.433 0.244 3. 讨论

ACHBLF的发生发展涉及固有免疫和获得性免疫的多个环节,已有许多研究[8]证实免疫细胞如树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、MDSC、T淋巴细胞等与ACHBLF的进展及预后密切相关,但尚未有研究评价这些细胞在pre-ACHBLF中的变化。本研究发现pre-ACHBLF患者中MDSC、Th17、Treg和Tc17均比CHB患者明显升高,提示ACHBLF前期已存在严重的细胞免疫功能紊乱。因此,关注患者的病期变化,对pre-ACHBLF患者及早进行干预,维持细胞免疫平衡,可能对防止疾病进展起到重要作用。

MDSC是机体重要的免疫抑制细胞,具有抑制固有免疫和适应性免疫应答的作用,参与多种炎症和免疫性疾病的发生发展。近年来,一些研究[9]相继分析了MDSC在ACHBLF中的作用,发现ACHBLF患者MDSC频数明显升高,且随患者病期程度加重,本研究也证实了以上结果。为了探讨MDSC在ACHBLF疾病进程中的变化,本研究还观察了pre-ACHBLF患者中MDSC的频数,结果发现pre-ACHBLF患者中MDSC频数明显高于CHB患者,且高于ACHBLF患者。推测随着各种诱因导致CHB患者病情加重,肝细胞坏死及炎症反应产生的多种因子诱导机体MDSC快速升高,以抑制过强的免疫反应;而在ACHBLF发生时,机体以免疫炎症反应占主导,使MDSC频数相应降低。目前国内外关于MDSC在CHB-pre-ACHBLF-ACHBLF进程中如何发挥作用的研究还很少,尚需要进一步深入探讨。

值得注意的是,笔者团队观察到MDSC和Treg细胞的变化过程存在差异,MDSC水平在pre-ACHBLF患者中最高,而Treg细胞在ACHBLF患者中更高,此结果提示MDSC的增殖具有相对前置性,这两类重要的抑制性细胞在ACHBLF进展的不同时期分别发挥作用。此外还发现pre-ACHBLF患者中MDSC水平与炎症指标之间存在正相关性,而Treg水平仅与白细胞数呈正相关。目前炎症和免疫反应是ACHBLF发生发展过程中的重要病理生理机制,随着系统性炎症反应综合征的发生,炎症介质的持续释放导致ACHBLF患者出现血管内皮障碍,毛细血管渗漏和组织灌注不足而引起微循环紊乱, 继而引发器官衰竭。既往研究表明循环炎症介质及肝细胞坏死释放的损伤相关模式分子等可促进MDSC的增殖和分化[10],而MDSC具有诱导Treg细胞扩增和分化的作用[11-12]。因此,这些研究提示在肝衰竭前期,过强的炎症反应激活MDSC使其表达升高,形成以MDSC为主的免疫抑制状态;随着疾病进展,MDSC诱导Treg细胞表达,转变为以Treg细胞为主的状态。

Th17和Tc17是以分泌IL-17为主要特征的T淋巴细胞亚群,他们有着共同的分化刺激因子及分化调节通路,共同在炎症性疾病、病毒感染、自身免疫性疾病、肿瘤等疾病中发挥作用[13]。但是,这两类细胞在许多方面如分子和代谢调节网络、可塑性、表达变化也存在差异[14]。一项肝癌相关的研究[15]显示,肝癌组织中分泌IL-17的细胞主要是Tc17细胞,而外周血中则主要是Th17细胞。在ACHBLF病理损伤过程中,已有大量研究证实ACHBLF患者的Th17细胞明显升高,且与预后密切相关[16],但仅有极少数研究报道了Tc17细胞在ACHBLF发生发展中的作用[17-18], 特别是罕有研究观察Tc17细胞在pre-ACHBLF患者的表达。本研究发现pre-ACHBLF和ACHBLF患者外周血Th17与Tc17细胞频数显著高于CHB患者,且Tc17的变化更明显,推测Th17与Tc17细胞可能协同参与ACHBLF的疾病进程。

综上所述,本研究发现pre-ACHBLF患者外周血MDSC、Treg、Th17细胞和Tc17细胞水平均明显升高,特别是MDSC表达与炎症指标呈密切相关性。尽管本研究病例数偏少,但研究结果对理解ACHBLF的疾病进展具有重要意义。将来进一步扩大样本量进行验证,并深入探讨这些免疫细胞的作用机制,将为ACHBLF早期抗免疫治疗提供更多的理论依据。

-

表 1 患者基线特征

指标 全部患者(n=1239) 非肝硬化组(n=1108) 肝硬化组(n=131) 统计值 P值 年龄(岁) 39.4±11.8 38.3±11.5 48.3±10.8 t=9.506 <0.001 男/女(例) 912/327 809/299 103/28 χ2=2.228 0.522 HCC家族史[例(%)] 74 (6.0) 61 (5.5) 13 (9.9) χ2=3.997 0.046 饮酒史[例(%)] 285 (23.0) 280 (25.3) 28 (21.4) χ2=0.234 0.628 高血压[例(%)] 107 (8.6) 87 (7.9) 20 (15.3) χ2=12.621 <0.001 糖尿病[例(%)] 87 (7.0) 66 (6.0) 21 (16.0) χ2=12.425 <0.001 ALT(U/L) 112.4 (39.9~403.3) 129.0(44.7~442.3) 44.6 (27.3~106.2) Z=-5.010 <0.001 AST(U/L) 62.0 (30.8~191.1) 67.4 (32.3~204.0) 34.6 (26.2~85.3) Z=-3.541 <0.001 TBil(μmol/L) 16.1 (11.3~27.6) 15.9 (11.1~27.3) 18.6(13.4~29.0) Z=-0.337 0.736 Alb(g/L) 30.6(27.5~33.9) 41.5(37.8~45.4) 39.5(35.9~42.8) Z=-3.256 0.003 GGT(U/L) 59.7 (27.3~124.1) 61.0 (27.1~126.8) 50.6 (28.0~110.9) Z=-0.706 0.480 WBC(×109/L) 5.1 (4.2~6.1) 5.1 (4.2~6.2) 4.7 (3.1~5.7) Z=-2.882 0.004 PLT(×109/L) 153.0(115.5~197.5) 160.6(122.0~200.1) 100.6(76.0~129.0) Z=-9.572 0.001 BUN(mmol/L) 4.4 (3.5~5.4) 4.4 (3.7~5.3) 4.9 (4.2~5.9) Z=0.271 0.786 Cr(μmoI/L) 68.7 (59.0~77.0) 68.3 (58.8~77.0) 70.0 (59.8~77.0) Z=-0.002 0.998 PT(s) 12.2 (11.5~13.1) 12.1 (11.4~13.0) 12.7 (11.7~14.1) Z=2.922 0.004 INR 1.0 (0.9~1.1) 1.1 (1.0~1.1) 1.1 (1.0~1.2) Z=-0.195 0.846 AFP(ng/ml) 5.7 (2.6~25.9) 5.6 (2.9~24.9) 6.5 (3.3~29.4) Z=-0.634 0.405 HBV DNA(log10拷贝/ml) 5.5 (3.3~7.1) 5.7 (3.5~7.1) 3.9 (2.7~6.1) Z=-5.374 0.001 mFIB-4 1.6(0.8~2.9) 1.5(0.8~2.5) 3.6(2.3~7.3) Z=10.827 <0.001 FIB-4 1.6 (0.9~3.3) 1.5 (0.8~3.1) 3.2 (1.8~5.4) Z=3.194 0.001 APRI 1.5(1.1~2.2) 1.5(1.1~2.1) 2.1(1.5~2.8) Z=5.124 <0.001 抗病毒治疗[例(%)] 恩替卡韦 1239(100.0) 1108(100.0) 131(100.0) 之前服用抗病毒药物 312(25.2) 86(6.9) 226(18.3) 聚乙二醇化干扰素 35(2.8) 35(2.8) 0 表 2 CHB患者发生HCC风险的单因素分析

因素 HR(95%CI) P值 年龄 1.067(0.041~1.094) <0.001 男性 1.361(0.658~2.823) 0.407 HCC家族史 1.443(0.444~4.720) 0.540 饮酒史 1.222(0.591~2.525) 0.588 高血压 1.270(0.454~3.555) 0.660 糖尿病 0.374(0.051~2.734) 0.332 ALT 0.994(0.990~0.998) 0.003 AST 0.994(0.989~0.999) 0.014 TBil 0.984(0.966~1.003) 0.102 Alb 0.966(0.923~1.011) 0.139 GGT 0.996(0.991~1.001) 0.183 WBC 0.978(0.840~1.139) 0.978 PLT 0.984(0.978~0.990) <0.001 BUN 1.004(0.991~1.018) 0.530 Cr 1.009(0.999~1.019) 0.054 PT 1.049(0.938~1.114) 0.400 INR 0.991(0.803~1.222) 0.935 AFP 0.997(0.991~1.003) 0.361 HBV DNA 0.827(0.699~1.078) 0.271 -

[1] SINGAL AG, El-SERAG HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma from epidemiology to prevention: Translating knowledge into practice[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 13(12): 2140-2151. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.014. [2] HEIMBACH JK, KULIK LM, FINN RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(1): 358-380. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29086. [3] ARENDS P, SONNEVELD MJ, ZOUTENDIJK R, et al. Entecavir treatment does not eliminate the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: Limited role for risk scores in Caucasians[J]. Gut, 2015, 64(8): 1289-1295. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307023. [4] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 57(1): 167-185. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [5] JUNG KS, KIM SU, SONG K, et al. Validation of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma prediction models in the era of antiviral therapy[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 62(6): 1757-1766. DOI: 10.1002/hep.28115. [6] VALLET-PICHARD A, MALLET V, NALPAS B, et al. FIB-4: An inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest[J]. Hepatology, 2007, 46(1): 32-36. DOI: 10.1002/hep.21669. [7] WAI CT, GREENSON JK, FONTANAL RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C[J]. Hepatology, 2003, 38(2): 518-526. DOI: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [8] PAIK N, SINN DH, LEE JH, et al. Non-invasive tests for liver disease severity and the hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B patients with low level viremia[J]. Liver Int, 2018, 38(1): 68-75. DOI: 10.1111/liv.13489. [9] WANG HW, PENG CY, LAI HC, et al. New noninvasive index for predicting liver fibrosis in Asian patients with chronic viral hepatitis[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 3259. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-03589-w. [10] Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases and Chinese Society of Hepatology Chinese, Medical Association. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B: A 2019 update[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2019, 35 (12): 2648-2669. DOI: 1001-5256(2019)12-2648-22.中华医学会感染病学分会, 中华医学会肝病学分会. 慢性乙型肝炎防治指南(2019年版)[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2019, 35(12): 2648-2669. DOI: 1001-5256(2019) 12-2648-22. [11] Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases Chinese, Medical Association. Chinese guidelines on the management of liver cirrhosis[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2019, 35(11): 2408-2425. DOI: 1001-5256(2019)11-2408-18.中华医学会肝病学分会. 肝硬化诊治指南[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2019, 35 (11): 2408-2425. DOI: 1001-5256(2019) 11-2408-18. [12] OMATA M, CHENG AL, KOKUDO N, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma, a 2017 update[J]. Hepatol Int, 2017, 11(4): 317-370. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9. [13] CHAN SL, WONG VW, QIN S, et al. Infection and cancer: The case of hepatitis B[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(1): 83-90. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.5724. [14] CHAN HLY. Okuda lecture: Challenges of hepatitis B in the era of antiviral therapy[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 34(3): 501-506. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.14534. [15] PAPATHEODORIDIS GV, IDILMAN R, DALEKOS GN, et al. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma decreases after the first 5 years of entecavir or tenofovir in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B[J]. Hepatology, 2017, 66(5): 1444-1453. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29320. [16] PAPATHEODORIDIS GV, MANOLAKOPOULOS S, TOULOUMI G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with or without cirrhosis treated with entecavir: HepNet. Greece cohort[J]. J Viral Hepat, 2015, 22(2): 120-127. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.12283. [17] CHEN CF, LEE WC, YANG HI, et al. Changes in serum levels of HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase determine risk for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 141(4): 1240-1248, 1248. e1-e2. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.036. [18] TSENG TC. Risk factors of liver cancer progression in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection[J/CD]. Chin J Exp Clin Infect Dis (Electronic Edition), 2019, 13(5): 440. DOI: 10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-1358.2019.05.017.TSENG TC. 慢性乙型肝炎病毒感染者进展为肝癌的危险因素[J/CD]. 中华实验和临床感染病杂志(电子版), 2019, 13(5): 440. DOI: 10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-1358.2019.05.017. [19] KIM JH, KIM YD, LEE M, et al. Modified PAGE-B score predicts the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asians with chronic hepatitis B on antiviral therapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(5): 1066-1073. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.018. [20] BERZIGOTTI A, SEIJO S, ARENA U, et al. Elastography, spleen size, and platelet count identify portal hypertension in patients with compensated cirrhosis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(1): 102-111. e101. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.001. [21] THOMOPOULOS KC, LABROPOULOU-KARATZA C, MIMIDIS KP, et al. Non-invasive predictors of the presence of large oesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis[J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2003, 35(7): 473-478. DOI: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00219-6. [22] TANDON P, GARCIA-TSAO G. Portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma: Prognosis and beyond[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2006, 4(11): 1318-1319. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.009. [23] SUH B, PARK S, SHIN DW, et al. High liver fibrosis index FIB-4 is highly predictive of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61(4): 1261-1268. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27654. [24] KIM MN, KIM SU, KIM BK, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients with transient elastography-defined subclinical cirrhosis[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61(6): 1851-1859. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27735. [25] BAGLIERI J, BRENNER DA, KISSELEVA T. The role of fibrosis and liver-associated fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(7): 1723. DOI: 10.3390/ijms20071723. [26] GABELE E, BRENNER DA, RIPPE RA. Liver fibrosis: Signals leading to the amplification of the fibrogenic hepatic stellate cell[J]. Front Biosci, 2003, 8: d69-d77. DOI: 10.2741/887. [27] SAKURAI T, HE G, MATSUZAWA A, et al. Hepatocyte necrosis induced by oxidative stress and IL-1 alpha release mediate carcinogen-induced compensatory proliferation and liver tumorigenesis[J]. Cancer Cell, 2008, 14(2): 156-165. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.016. [28] FARAZI PA, DEPINHO RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: From genes to environment[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2006, 6(9): 674-87. DOI: 10.1038/nrc1934. 期刊类型引用(2)

1. 张雄乐,陈芬兰,林文. 甲泼尼龙联合抗病毒药物治疗对乙型肝炎早期肝衰竭患者肝功能及炎性因子的影响. 中国医药指南. 2023(34): 98-101 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 吴刚,叶晓玲,张宇,石磬. 单免疫球蛋白-白介素1受体蛋白在慢性乙肝患者中的表达水平变化及临床意义研究. 罕少疾病杂志. 2023(12): 72-74 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(3)

-

PDF下载 ( 2229 KB)

PDF下载 ( 2229 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术