Pathogenesis of drug-induced liver injury: Current understanding and future needs

-

摘要: 药物性肝损伤(DILI)的危险因素涉及人体因素(包括一般性非遗传因素和特异质性遗传及免疫因素)、药物因素和环境因素。其发生机制可分为固有(直接)肝毒性、特异质肝毒性和间接肝毒性,此外还有某些药物对肝脏的致瘤与致癌性。不同类型肝毒性的发生机制既有明显的区别,又有多环节的内在关联。以线粒体通透性转换(MPT)为中心的三步机制进程模型和以肝细胞再生及肝组织修复能力为转归节点的两阶段机制进程模型,从不同视角展示了DILI的机制进程。阐明DILI复杂的发生机制,需要长期的病例积累和系统研究,这对于其科学预防、诊断和治疗具有十分重要的意义。

-

关键词:

- 化学性与药物性肝损伤 /

- 危险因素 /

- 发病机制

Abstract: The risk factors for drug-induced liver injury (DILI) involve host factors (including general non-genetic factors and idiosyncratic genetic and immune factors), drug-related factors, and environmental factors. The pathogenesis of DILI can be classified as intrinsic (or direct) hepatotoxicity, idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity, and indirect hepatotoxicity, as well as tumorigenicity and carcinogenicity of some drugs to the liver. The pathogenesis of different types of hepatotoxicity not only has significant differences, but also has internal correlation at multiple links. The three-step model centered on mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and a two-stage model with liver cell regeneration and liver tissue repair capacity as the determinants of different outcomes display the mechanism progress of DILI from different perspectives. Clarification of the complex pathogenesis of DILI needs long-term collection of clinical cases and systematic studies, which is of great significance for the scientific prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of DILI.-

Key words:

- Chemical and Drug-Induced Liver Injury /

- Risk Factors /

- Pathogenesis

-

药物肝损伤(DILI)不仅是临床肝病(特别是急性肝损伤) 的常见原因之一,也是导致药物研发失败和上市后遭遇撤市最常见的原因之一,因而关注度越来越高[1-4]。DILI发病机制复杂,涉及到药物、人体乃至环境因素的多个方面。药物导致的肝毒性有多种,不同药物引起肝损伤的机制可能相似,也可能存在明显差异;同种药物在不同患者引起肝损伤的机制亦可能存在异同。阐明DILI的发病机制,对于其科学预防、诊断和治疗均具有十分重要的意义。本文特对DILI发病的危险因素、药物肝毒性的类型、药物导致肝损伤的机制进程等进行系统梳理和总结。

1. DILI发病的危险因素

与DILI相关的危险因素可归纳为患者因素、药物因素和环境因素三大类[1-3]。

1.1 患者因素

包括一般性因素、遗传多态性、肝细胞再生和肝组织修复能力的差异等。

1.1.1 一般性因素

1.1.1.1 年龄

虽然习惯认为年龄过大(55岁以上,特别是65岁以上)或过小(婴幼儿和低龄儿童)均与DILI的发生风险有一定的相关性,但迄今尚缺乏充分的循证医学证据能够证实这种相关性,各大指南[1-4]基于相关研究数据对年龄与DILI风险相关性的解读也不一致。老年人DILI发病率高,虽然可能有肝肾等器官功能衰退、药物代谢和清除能力减退因素的影响,但也很可能与老年人相关疾病处方药增多有关[5]。儿童,特别是婴幼儿,某些药物代谢系统尚未发育成熟,加之该年龄段特有的一些病种,使得儿童似乎对某些药物的肝毒性特别敏感[2-3]。目前较为严谨的提法应是,对多数药物而言,只要根据年龄按规范用药,则年龄并非DILI的一般性风险因素[2];但年龄与特定药物所致DILI的风险有一定的相关性,表现出一定程度的药物特异性[3],例如婴幼儿和儿童对于抗惊厥药(丙戊酸钠所致DILI在10岁特别是2岁以下小儿更多见)、米诺环素、阿司匹林、丙基硫氧嘧啶(PTU)相关肝损伤更敏感;而异烟肼(特别是50岁以上人群)、阿莫西林-克拉维酸和呋喃妥因相关肝损伤的风险随年龄增高而增大。

1.1.1.2 性别

虽然有研究[4]认为女性对DILI的易感性一般高于男性,但并无证据显示妇女对所有药物肝毒性的易感性均高于男性[3];西班牙、美国和冰岛的研究[2]均显示DILI患者的男女比例并无显著差异。因此,较为客观的观点是性别作为DILI的易感性因素总体上并不确切,但妇女对某些药物如米诺环素、甲基多巴、呋喃妥因和奈韦拉平等药物所致DILI的易感性可能更高[2-3]。米诺环素、甲基多巴、呋喃妥因和双氯芬酸所致DILI的典型特征是类似于自身免疫性肝炎(AIH)的慢性肝炎,女性多见[1-2]。少数研究[2]提示女性发生药物性肝衰竭的风险可能更高,但这尚需更多的临床队列加以比较分析。

1.1.1.3 妊娠

对于大多数药物而言,妊娠与DILI的相关性并不明确,即并无证据显示妊娠可使妇女对DILI的易感性增加[2-3]。实际上,DILI只是妊娠期急性肝损伤的少见病因,且一般是不常使用的处方药如四环素、甲基多巴、肼苯哒嗪、抗逆转录病毒药物、PTU等。其中PTU可致孕妇暴发性肝炎,病死率高,应特别注意。了解这些特点,有助于妊娠期肝内胆汁淤积综合征和妊娠期急性脂肪肝与DILI之间的鉴别。

1.1.1.4 基础疾病

相对严重的基础疾病,特别是病毒性肝炎、脂肪性肝炎、肝硬化等基础肝病及糖尿病等,可能会增加患者对DILI的易感性[6]。

1.1.2 遗传特异质性

DILI相关遗传特异质性危险因素涉及到药物代谢、人类白细胞抗原系统(HLA)、细胞因子等各种免疫分子、氧化应激和抗氧化应激相关分子、肝脏再生和修复相关分子、各种信号传导通路分子等诸多基因的遗传多态性,其中最受关注的是与药物代谢过程和HLA相关的遗传多态性及其所决定的功能表型多态性。

1.1.2.1 与药物代谢过程相关的遗传多态性

药物经肝脏的代谢分为四个阶段。第一阶段是药物向肝细胞内的转运过程,涉及有机阴离子转运多肽和转运蛋白、有机阳离子转运蛋白或Na+依赖性牛磺酸盐协同转运多肽等溶质转运载体。第二阶段(Ⅰ相代谢)是非极性药物(脂溶性药物)极性化(增加水溶性)的过程,涉及细胞色素P450酶(CYP)、单胺氧化酶、乙醛脱氢酶等代谢酶的作用。第三阶段(Ⅱ相代谢)是使极性化药物与内源性极性化合物结合并生成水溶性化合物的过程,涉及尿苷二磷酸葡萄糖醛酸转移酶(UGT)、N-乙酰基转移酶2(NAT2)、超氧化物歧化酶等的作用。第四阶段是水溶性药物代谢产物自肝细胞内向肝细胞外(胆道或血流)排泌的过程,相关转运分子主要是肝细胞表面ATP结合盒(ABC)超家族的跨膜转运蛋白,即多药耐药蛋白(MDR)和多药耐药相关蛋白(MRP),包括MDR1(ABCB1)、MDR3(ABCB4)、MRP2(ABCC2)和胆盐外排泵(BSEP,ABCB11)等。各种转运分子在人群中具有丰富的遗传多态性,在不同个体之间可存在较大的活性差异,是DILI特别是药物性胆汁淤积的重要危险因素和机制之一[7]。例如,有机阴离子转运蛋白特异性地分布在肝细胞血管膜面,其遗传多态性与利福平等许多药物转运入肝脏的能力大小密切相关。Ⅰ相和Ⅱ相代谢酶,特别是CYP、UGT和NAT等的基因多态性,也是多种类型DILI的危险因素。例如CYP2E1的基因多态性可显著影响不同个体对于对乙酰氨基酚(APAP)等诸多药物的肝毒性[8],CYP7A1等的遗传多态性可能与抗结核药物相关肝损伤的风险大小有关[9]。NAT2有快乙酰化型和慢乙酰化型之分,慢乙酰化型与异烟肼肝毒性的增加明显相关[10]。谷胱甘肽S转移酶(GST)有GSTM1和GSTT1之分,其中GSTM1缺失性基因型与抗结核药物诱发肝损伤的风险密切相关[11]。

1.1.2.2 与HLA相关的遗传多态性

HLA是最富多态性的人类基因。特定的HLA免疫遗传学背景,可使某些患者对某些药物肝毒性的易感性明显增加,成为具有遗传特异质和免疫特异质双重性质的特异质型DILI的高危因素。表 1总结了文献[2, 12-14]报道的HLA遗传多态性与部分药物所致DILI的相关性。

表 1 HLA遗传多态性与特定药物所致DILI的相关性HLA基因单倍型 相关药物(患者阳性率) 相关性或对照组阳性率 A*02∶01 阿莫西林-克拉维酸 相关 A*31∶01 卡巴咪嗪(17%) 正常对照组阳性率2% A*33∶01 噻氯匹定(80%),甲基多巴(50%),依那普利(50%),

非诺贝特(43%),特比萘芬(43%),舍曲林(40%),

红霉素(20%)正常对照组阳性率1% A*33∶03 噻氯匹定 相关 B*18∶01 阿莫西林-克拉维酸 相关 B*35∶01 何首乌(41.1%) 其他原因DILI阳性率11.9% 汉族MHC数据库阳性率2.7% B*35∶02 米诺环素(16%) 正常对照组阳性率0.6% B*57∶01 氟氯西林(84%~87%) 正常对照组阳性率6% DQA1*01∶02 卢米考昔 相关 DRB1*01∶01 奈韦拉平 相关 DRB1*15∶011)/DRB5*

01∶01/DQB1*06∶02阿莫西林-克拉维酸(57%~67%)

罗美昔布

氟烷正常对照组阳性率15%~20%

强相关

强相关DRB1*07∶012)/DQB1*

02∶02/DQA1*02∶01拉帕替尼

希美加群相关

相关DRB1*16∶01/DQB1* 05∶02 氟吡汀(25%) 正常对照组阳性率1% 注:1)与药物性胆汁淤积的发生强相关; 2)可使氟氯西林诱导DILI的风险增加81~100倍以上。 1.1.3 肝细胞再生和肝组织修复能力的差异

不论是何种机制引起的肝损伤,肝脏都必然要通过肝细胞再生和肝组织修复以对抗肝损伤。肝细胞再生和肝组织修复能力与遗传和非遗传因素均有密切相关性,受到物种、种族、年龄、基础肝病、肝外基础疾病等诸多因素的影响[15]。其中,与肝组织再生和修复能力相关的遗传性因素也可视为一种特殊的遗传特异质性因素(参见本文5.2部分)。

1.2 药物因素

药物的理化性质(例如亲脂性的大小)、活性代谢产物(reactive metabolites,RM)、日剂量(特别是大于100 mg/d时)和疗程、生物学活性(可能诱发间接肝毒性)、药物配伍及相互间作用,以及传统草药种植和炮制过程中的污染等因素,均可能与DILI的发生风险有不同程度的相关性[1-3]。

1.3 环境因素

饮酒、吸烟、周围环境污染(如房屋劣质装修和环境化工毒物污染)、染发和染指趾甲等,均有可能造成一定程度的基础性肝损伤,增加DILI的发生风险,风险大小因人而异。

2. 药物肝毒性的分类

药物肝毒性的类型,根据关键机制的不同可分为直接肝毒性(固有肝毒性)、特异质肝毒性和间接肝毒性,并呈现不同的临床特征(表 2)。除了这三种肝毒性类型外,某些药物还具有致瘤或致癌性,例如雄激素和口服避孕药与肝腺瘤的相关性[16],马兜铃酸与肝细胞癌的相关性[17],这类特殊的DILI此处不做叙述。

表 2 三种药物肝毒性类型的比较1)项目 固有(直接)肝毒性 特异质肝毒性 间接肝毒性 发生机制 药物及其活性代谢产物的固有(直接)肝毒性,以及人体固有的病理生理性损伤反应 与人体遗传多态性相关的特异质性药物代谢障碍,或药物-宿主蛋白加合物特异性、HLA限制性获得性免疫应答 继发于药物或其活性代谢产物的生物学活性,多通过影响免疫系统而间接对肝脏产生毒性作用 发生率 对具体药物而言,常见 对具体单药而言,少见。对药物整体而言,常见 随具体药物生物学活性特点的不同,可从少见到较为常见 剂量相关 明显的剂量依赖性 不明显(但阈剂量通常也需达到50~100 mg/d) 有一定程度的剂量和疗程相关性 可预测性 多可预测 难以预测 部分可预测 可复制性 常可在动物模型复制 难以在动物模型复制 有可能在动物模型复制 潜伏期 通常很快(数日内) 相差较大:数日至数月乃至1年以上 一般较迟出现(数月) 临床表型 肝酶升高,急性肝坏死,肝窦阻塞综合征,急性脂肪肝,结节性再生,等 急性肝细胞损伤,淤胆性肝炎,混合性肝炎,单纯性胆汁淤积,慢性肝炎,等 急性肝炎,免疫介导的肝炎,脂肪肝,慢性肝炎,等 常见涉及药物 APAP、阿司匹林、甲氨蝶呤等抗肿瘤化疗药物、高效抗逆转录病毒药物、合成代谢类甾族激素、他汀类药物、环孢霉素、肝素、丙戊酸、烟酸、丁酸、可卡因、胺碘酮、他克林、消胆胺、含有吡咯双烷生物碱的草药,等 阿莫西林-克拉维酸、氟氯西林、头孢菌素类、大环内酯类、曲伐沙星等喹诺酮类、磺胺类药物、异烟肼、吡嗪酰胺、酮康唑、特比萘芬,呋喃妥因、米诺环素,別嘌呤醇、丙基硫氧嘧啶,双氯芬酸、来氟米特、噻氯匹定、拉帕替尼、帕唑帕尼、氟他米特、他汀类药物、非诺贝特、丹曲林、胺碘酮、氟烷、托伐普坦、赖诺普利、甲基多巴、波生坦、托卡朋、苯妥英、戒酒硫、菲尔安酯,等 免疫检查点抑制剂、抗肿瘤坏死因子单抗、抗CD20单抗、蛋白激酶抑制剂、糖皮质激素、某些抗肿瘤药物、影响和干扰物质及能量代谢的相关药物,等 注:1)根据参考文献[18-19]进行必要修改。 3. 不同类型药物肝毒性的发生机制

3.1 固有(直接)肝毒性

药物的固有肝毒性也称为药物的直接肝毒性,是由对肝脏存在固有或直接毒性的药物所引起。其致病启动因素在于药物本身的理化特性(特别是亲脂性、毒性代谢产物)及剂量,但也需通过引发患者体内特别是肝内一系列病理生理反应而导致肝损伤。相关药物(表 2)所致DILI常具有剂量依赖性、可预测性、动物模型可复制性[1-3, 19]。APAP是固有肝毒性药物的典型代表,在合并用药、饥饿、全身性疾病、慢性酒精滥用等情况下,CYP2E1和GSH的水平受到干扰,可影响APAP的中毒阈值[2]。

3.1.1 固有肝毒性的药物因素

根据药物的亲脂性和日剂量,有学者提出了两因素规则或模型(Rule-of-2,RO2),亦即如果药物的亲脂性logP≥3,且口服剂量≥100 mg/d[20],则这种药物很可能具有肝毒性。根据这个模型,可以判断出大多数具有直接肝毒性的药物,但难以预测引起DILI的严重程度。后来,在RO2模型的基础上又融入了RM因素,构建了DILI评分模型,即方程为0.608×log(日剂量mg+0.227×logP+2.833×(RM形成)。如果该评分≥7,则提示药物与严重程度4级或危及生命的肝损伤相关[20]。这些理论或模型尚需进一步研究论证。

3.1.2 固有肝毒性的人体因素

固有肝毒性的宿主因素包括药物及其RM引起的体内特别是肝内的各种非特异性反应,包括药物及其RM与宿主蛋白的结合,谷胱甘肽(GSH)等抗氧化系统的耗竭,应激性激酶的活化,线粒体应激释放活性氧(ROS)等强氧化性基团及线粒体功能障碍,内质网应激,以及固有免疫系统的活化和肝脏局部炎症反应等[2, 18]。

3.2 特异质肝毒性

此类药物无明显的固有毒性或只有极小的固有毒性,肝损伤的发生主要与患者特异体质相关。对某种具体药物而言,通常仅在极少数患者引起肝损伤,例如在2000~100 000例患者发生暴露后出现1例肝损伤[18]。但如果把所有药物视为一个整体,则特异质肝毒性是DILI(特别是急性DILI)较为常见的病因。特异质肝毒性机制主要分为免疫特异质和代谢特异质两大方面。此外,肝细胞再生和肝组织修复能力也可能受到遗传特异质(种族及个体间的遗传多态性)和非遗传因素(年龄、基础肝病和糖尿病等)的双重影响[21-23]。

3.2.1 免疫介导的特异质肝毒性

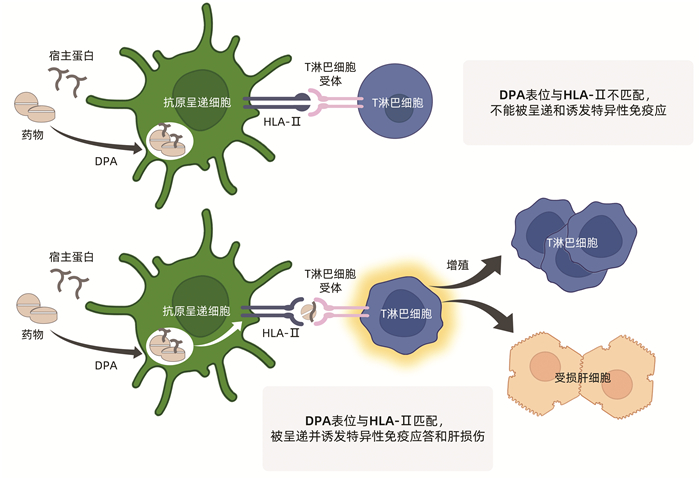

即HLA限制性获得性免疫应答,是临床上最为常见的特异质肝毒性机制,与药物和宿主因素均密切相关。药物或其代谢产物与宿主蛋白形成的药物-蛋白加合物(drug-protein adducts,DPA)提供合适的抗原表位,而宿主则提供HLA限制性免疫应答通路。

实际上,药物与宿主血清蛋白形成DPA是十分常见的现象,以便于药物的运输、代谢和清除。药物特别是其RM在肝细胞内的代谢过程中也常需与相关蛋白分子结合形成DPA。但大多数DPA在绝大多数患者并不诱发免疫特异质DILI(图 1a)。仅在极少数患者,DPA含有对应于某种HLA多态性的抗原表位时,才可能被巨噬细胞和树突状细胞等抗原呈递细胞捕获、处理并呈递给HLA-Ⅱ限制性T淋巴细胞,进而诱发HLA限制性DPA特异性免疫应答介导的肝损伤(图 1b)[24]。这种特异性免疫应答理论上可分为三种情况,其一是如果DPA抗原表位来自于药物半抗原,则将产生抗药物特异性免疫反应;其二是如果DPA抗原表位来自于宿主蛋白,则将产生具有自身免疫特征的特异性免疫反应;其三是在罕见情况下,可能有同时针对DPA的药物半抗原表位和宿主蛋白表位的特异性免疫反应,这将导致抗药物免疫反应和自身免疫反应同时存在的情况。

3.2.2 药物代谢通路相关的遗传多态性

药物代谢通路中众多的转运蛋白/多肽和代谢酶有着复杂的基因多态性(参见上文第1.1.2部分),某些基因多态性可能会引起药物及其RM在肝脏的蓄积,进而通过直接细胞应激和/或直接线粒体损伤等毒性机制(参见下文第5.1.1部分)引起肝细胞等靶细胞的损伤。药物及其RM在肝细胞和体内的蓄积还可能竞争性抑制胆红素、胆汁酸和胆盐等物质的代谢和排泌,进而引起继发性或次级肝损伤和肝功能障碍。此外,不排除某些药物和某些患者,药物及其RM的蓄积也可能引起特异性免疫介导的肝损伤。

3.3 间接肝毒性

药物的间接肝毒性是指继发于药物生物学效应的肝毒性,不是药物的固有肝毒性或特异质肝毒性[18]。间接肝毒性可独立出现,但由于继发于药物生物学作用的毒性效应多不具有特定器官靶向性,因此可先后或同时伴有肝外其他组织器官的损伤[25]。

目前报告的药物间接肝毒性大致有以下几种:(1)PD1单抗、PDL1单抗、CTLA-4单抗等抗肿瘤免疫检查点抑制剂(ICIs)的间接肝毒性,可能主要与ICIs应用后广泛的继发性免疫激活相关[26-29]。(2)肿瘤坏死因子拮抗剂的间接肝毒性,可能主要与干扰体液和细胞免疫有关,尤其是原有自身免疫性疾病的患者[30-31]。(3)抗CD20单抗[18]。(4)蛋白激酶抑制剂[18]。(5)甲基泼尼松龙经静脉大剂量重复脉冲式(每次500~1000 mg/d,连续3 d)治疗多发性硬化等自身免疫疾病后的间接肝毒性,并且再用药后的肝损伤再激发率较高,可能与短期过度免疫抑制再撤药后的免疫重建相关[32]。(6)某些其他抗肿瘤药物的间接肝毒性[18]。(7)干扰物质和能量代谢药物的间接肝毒性,常可引起脂肪肝,例如可导致体质量增加的药物(如利培酮和氟哌啶醇),能直接结合并抑制肝细胞和小肠细胞微粒体甘油三酯转运蛋白(MTP)、从而干扰脂代谢的药物(如洛美他派),能改变胰岛素敏感性的药物(如糖皮质激素)[18]。上述7种情况中,以ICIs、肿瘤坏死因子拮抗剂和抗CD20单抗等引起的免疫相关间接肝毒性最受关注。

伴有HBV或HCV感染的恶性肿瘤、自身免疫性疾病患者,若接受化疗、放疗或免疫抑制治疗,可能会引起HBV或HCV的再激活,从而引起病毒性肝炎复发或急性加重[33],严重者可引起纤维淤胆性肝炎/免疫诱导性肝衰竭[34-35]。伴有HBV或HCV感染的人类免疫缺陷病毒(HIV)感染者,应用高效抗逆转率病毒治疗(HAART),可能会因免疫重建导致对HBV或HCV免疫增强而出现病毒性肝炎发作的情况;或HIV感染终末期、极度免疫抑制状态下,出现HBV和HCV的高复制,引起所谓免疫抑制诱导的肝炎病毒相关肝衰竭[35]。这些情况下的肝损伤虽然也与肿瘤化疗药物、免疫抑制药物或HARRT药物的生物学效应间接相关,但根源是原先存在HBV或HCV感染,属于特殊人群的病毒性肝炎范畴,在不需停用化疗或免疫抑制药物的情况下,应用口服抗HBV或抗HCV药物即可有效控制HBV或HCV复制及肝损伤。此外,在应用聚乙二醇干扰素治疗慢性乙型肝炎的过程中,也可因HBV特异性免疫激活而出现肝酶升高。这些情况与严格意义上的药物间接肝毒性不同。

4. DILI不同发病机制的内在区别与关联

DILI不同发病机制之间有着明确的差别[18],主要体现在:(1)固有肝毒性的剂量依赖模式较为明显,人体固有(直接)病理生理反应相对强烈。(2)特异质DILI主要是由特定的HLA限制性DPA特异性获得性免疫应答介导,和/或由于特定的药物代谢通路异常所致。(3)间接肝毒性是继发于药物生物学活性特别是免疫学活性的一种毒性效应;对于此类药物而言,虽然不排除也具有潜在的固有肝毒性或特异质性肝毒性,但间接性肝毒性显然更为引人注目。

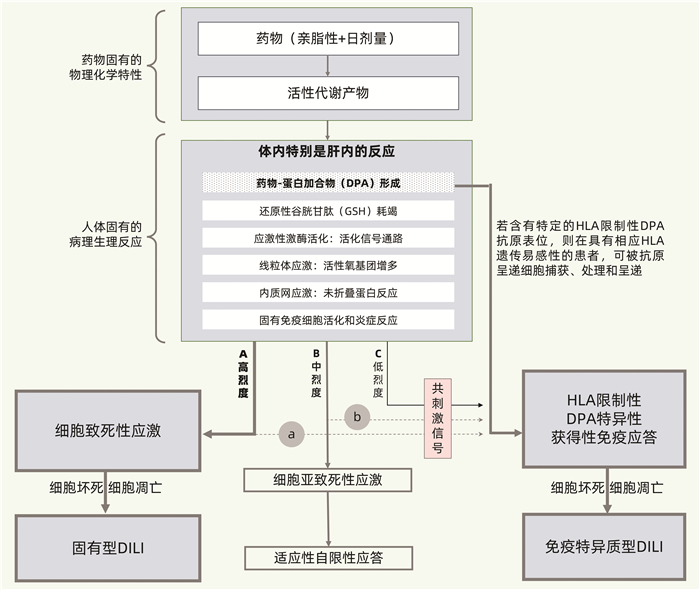

固有型肝毒性和免疫特异质肝毒性的区别与联系参见图 2[2]。首先,如图 2-A所示,药物特别是其RM可与宿主蛋白共价结合,形成DPA,引起氧化应激反应,激活多种固有免疫和炎症信号通路,诱发线粒体和内质网等细胞器应激,干扰肝脏生物合成、转化和转运等多种功能。若这些固有损伤反应呈高烈度,明显超过患者体内的还原性GSH等抗氧化系统及其他保护机制的制衡能力,则将导致肝细胞等靶细胞的坏死和凋亡等严重后果,发生固有型DILI。其次,如图 2-B所示,若上述固有病理生理性损伤反应呈中烈度,且体内能及时出现充分的抗氧化反应、内质网未折叠蛋白反应以及线粒体生物合成等保护性反应,则可避免发生严重肝损伤,不出现明显的、或仅出现短暂轻度肝损伤,表现为对药物固有肝毒性的适应性。再者,如图 2-C所示,若上述固有病理生理反应呈低烈度,则通常不引起明显的、或仅伴有轻微的固有型肝损伤;但若DPA的抗原表位恰巧对应于患者特定的HLA遗传背景,则将启动HLA限制性DPA特异性获得性免疫应答,导致免疫特异质型DILI。固有免疫系统等的激活可为这种免疫特异质反应提供共刺激信号。

固有肝毒性和特异质肝毒性并不是截然分割的,某些药物既可导致不同程度的固有肝毒性,也可引起特异质肝毒性(如图 2中的A+a和B+b所示)。即便是典型的固有肝毒性药物APAP,也不排除在特定环境条件下具有个体特异体质相关性[8, 36]。虽然多数患者在服用APAP达到或超过10~15 g/d时出现肝损伤,但某些患者(特别是饮酒者)即使服用不足4 g/d也可出现肝损伤;而另有部分患者则能耐受超大剂量APAP[36-37]。再如,虽然一般认为特异质肝毒性没有明显的剂量相关性,但绝大多数药物在日剂量不足10 mg/d时极少发生特异质DILI;而氟烷诱导的超敏性肝毒性往往在更高剂量时较易发生[36]。此外,异烟肼被认为具有较低的固有肝毒性和较强的特异质肝毒性[36];胺碘酮和他汀类等药物被认为既具有固有肝毒性,又可引起特异质肝毒性[2]。

不论是固有、特异质还是间接肝毒性,最终均将导致肝细胞线粒体损伤和功能障碍,引起不同程度和范围的靶细胞损伤和死亡(图 2、3)[2, 36]。DILI最常受损的靶细胞是肝细胞和胆管上皮细胞,某些药物或毒物(如含有吡咯双烷生物碱的土三七等)则以肝窦和肝小静脉等血管的内皮细胞为主要靶细胞。根据2018年细胞死亡命名委员会指南[38],细胞死亡形式包括内源性细胞凋亡、外源性细胞凋亡、线粒体通透性转换(mitochondrial permeability transition,MPT)驱动的细胞坏死、坏死性凋亡、铁死亡、细胞焦亡、PARP1依赖性细胞死亡、同类细胞相食性细胞死亡、NET驱动的细胞死亡、溶酶体依赖性细胞死亡、自噬依赖性细胞死亡、免疫原性细胞死亡、细胞衰老和有丝分裂障碍等14种形式。此外还提出细胞内碱化作用驱动的凋亡和氧自由基诱导的半胱天冬酶非依赖性凋亡等细胞死亡形式[39]。DILI发病机制可能涉及其中多种细胞死亡形式,特别是细胞凋亡、MPT驱动的细胞坏死、坏死性凋亡和细胞焦亡等。

总之,虽然不同类型肝毒性的发生机制差异显著,但并非绝对的非此即彼、完全割裂的关系。固有型DILI和特异质型DILI的发病机制,在引发肝毒性的通路上存在着多个环节的交结或内在关联(图 2、3)[2, 36]。这种内在的交结或关联主要体现在四大方面:其一,肝损伤的启动在总体上均与药物的固有理化特性(特别是亲脂性)、日剂量(虽然差异明显)及RM有不同程度的关联;其二,均存在人体固有免疫及炎症反应,虽然其程度、范围及时限等方面存在较大差别;其三,遗传特异质药物代谢障碍引起药物特别是RM在体内蓄积后,后发毒性效应可具有固有型肝毒性的相关特征;其四,线粒体损伤和MPT处于肝损伤发生的中心环节,不论何种肝毒性,只要达到一定强度,均将导致范围和程度不等的靶细胞死亡。

5. DILI的发病机制进程

固有型DILI和特异质DILI的发病机制进程可借助相关模型加以说明[21, 36]。

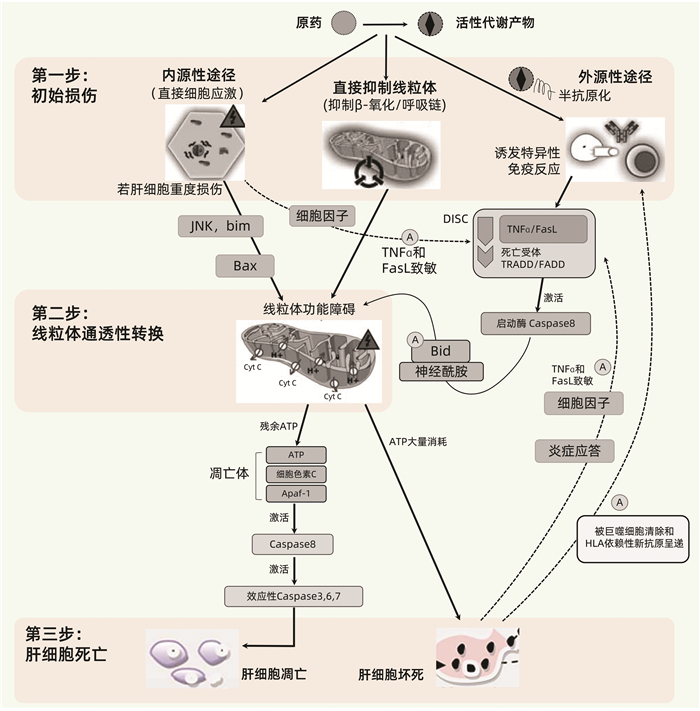

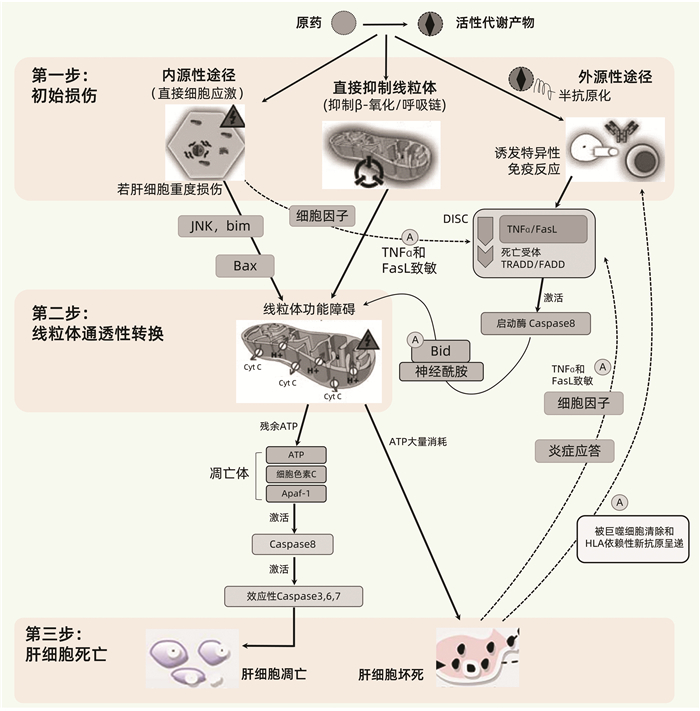

5.1 药物肝毒性的三步机制进程模型

该模型由Russmann等[36]于2009年提出,将DILI的发生机制进程大致分为上游事件(第一步)和下游事件(第二、三步)(图 3),并展示了固有肝毒性(内源性途径)和免疫特异质肝毒性(外源性途径)之间的差别与关联,提出MPT在各种DILI的发病机制中均处于中心地位,其损伤程度决定着肝细胞是发生凋亡还是坏死。三步模型特别有助于从整体上理解DILI的一般性发病机制进程。但需注意,DILI发病机制过程复杂,很难通过一个工作模型加以完整反映,主要体现在以下几点:(1)某些药物RM可跳过第一步,直接活化死亡受体或细胞防御系统等下游事件,例如N-乙酰-对-苯醌亚胺(NAPQI)可直接活化Keap1-Nrf细胞防御系统[40];(2)未能体现损伤性反应与保护性反应(包括抗氧化反应和肝组织的再生修复能力)之间的制衡性;(3)未能体现与药物转运和转化相关的遗传代谢性特异质肝毒性机制;(4)该模型是在2009年提出,未能反映近年来得到关注的间接肝毒性机制。

5.1.1 第一步:药物肝毒性的启动机制

DILI发病的启动机制包括药物或RM引发的直接细胞应激、直接线粒体损伤和/或特异性免疫反应。一般情况下这些反应由RM引起,而由原药引起者相对较少。多数情况下这些反应主要损伤肝细胞,其次是胆管上皮细胞(如氟氯西林),有些药物RM则主要靶向于肝内血管内皮细胞(如吡咯双烷生物碱)。

Ⅰ相代谢酶CYP家族是介导产生RM最重要的代谢酶。Ⅱ相代谢酶也可介导产生RM,例如具有肝毒性的酰基葡萄糖苷酸。药物和RM可通过多种机制直接引起相关初始细胞应激,例如耗尽GSH,与酶、脂质、核酸和其他细胞结构结合,抑制胆盐输出泵(BSEP,ABCB11基因);而BSEP等的抑制又可导致其底物蓄积,进而产生次级肝毒性。

某些药物或RM可能在初始阶段就能直接抑制肝细胞线粒体呼吸链,导致ATP减少、耗竭和增加ROS的产生,抑制β-氧化和引起肝细胞脂肪变性,损伤线粒体DNA和干扰其复制;或直接导致MPT,使得线粒体上的小孔开放。

药物或RM与宿主蛋白共价结合形成的DPA可充当新抗原,在具有特定HLA遗传背景的患者诱导HLA限制性DPA特异性免疫应答,包括细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(CTL)的活化、细胞因子的产生、抗药物半抗原抗体或抗宿主蛋白自身抗体(例如抗CYP抗体)的产生等。

5.1.2 第二步:MPT

MPT可在第一步的初始阶段就被某些药物或RM直接引起,但多数情况是在第二步中通过强烈的细胞应激(内源性途径)直接被启动,或通过死亡受体放大的通路(外源性途径)间接被启动,后者常由较轻的细胞应激和/或特异性免疫应答引起。

在内源性途径中,强烈的细胞应激可激活内质网通路、溶酶体透化或JNK激酶等;随后激活Bcl-2家族的促凋亡蛋白(例如Bax、Bak、Bad),并抑制抗凋亡蛋白(如Bcl-2和Bcl-xL),从而导致MPT。

在外源性途径中,初始轻度损伤可被轻度应激引起的炎症反应所放大,而附加因素可调节人体的固有免疫系统,调控促炎细胞因子如IL-12和抑炎细胞因子如IL-4、IL-10、IL-13及单核细胞趋化蛋白-1之间的平衡。其后果之一是敏化的肝细胞对TNF、Fas配体(FasL)和IFNγ的致死性效应十分敏感。若初始损伤事件是特异性免疫反应,则HLA限制性抗原呈递将激活肝脏Kuffer细胞和CTL释放TNF及FasL。TNF和FasL与肝细胞内的死亡受体结合,继而激活TNF相关死亡域蛋白(TRADD)和Fas受体相关死亡域蛋白(FADD),TNF/FasL、死亡受体和TRADD/FAD形成死亡诱导信号复合体,继而激活启动酶Caspase-8。Caspase-8可直接活化效应性Caspase-3/6/7,从而启动靶细胞凋亡;但这种直接信号通路对肝细胞而言往往太弱而难以启动凋亡,故需借助Bcl-2家族促凋亡蛋白(例如Bid)和神经酰胺进行信号放大。与内源性通路相似,这将导致MPT;而MPT是内源性通路和外源性通路所致DILI的共同环节,在DILI发病机制中起关键作用,进一步介导靶细胞死亡[41]。参考自身免疫性肝病的“危险信号假设”,单纯半抗原很难独自激发HLA限制性过敏性肝毒性;但在药物或RM所致轻度细胞应激,或同时存在其他炎性疾病的状态下,伴随释放的损伤性细胞因子可提供“危险信号”,从而辅助激活特异性免疫反应,引发免疫特异质型肝损伤[42]。

5.1.3 第三步:肝脏靶细胞的死亡(凋亡或坏死)

MPT可导致大量质子流穿越线粒体内膜,从而阻碍或终止线粒体ATP的合成。因此,MPT或其他能直接毁损线粒体的机制可引起线粒体ATP耗竭,导致线粒体基质肿胀、外膜通透性增加和破裂,细胞色素C和其他促凋亡线粒体蛋白从膜间隙释放至细胞质。细胞色素C结合至胞质支架(Apaf-1)和Caspase-9,形成凋亡体,从而活化Caspase-9;该耗能过程需要ATP的参与,因此仅在仍有部分线粒体保持完整并能合成ATP的情况下。活化的Caspase-9和其他可能的促凋亡线粒体蛋白激活效应性Caspase-3,Caspase-3继而切割特定的细胞蛋白并进一步活化Caspase-6/7/2,最终导致程序性凋亡性细胞死亡。凋亡相当于一种“安静的”细胞死亡,凋亡片段随之被巨噬细胞清除,该过程仅伴有轻微的炎症,因而继发性损害也很轻微。

若初始损伤强烈,以至于肝细胞的所有线粒体都迅速发生MPT,或有其他机制导致线粒体ATP迅速耗竭,从而阻止了凋亡的发生,这将导致靶细胞的坏死。缺乏ATP也可激活内源性途径导致靶细胞坏死。坏死的细胞可诱发炎症反应,细胞因子释放,从而通过敏化周围的肝细胞而放大初始损伤效应。

细胞凋亡和坏死并非总是泾渭分明,两者可以混合存在[36]。此外,DILI相关细胞死亡形式可能不止传统的凋亡和坏死这两种,因为近年来发现的细胞死亡形式多达12~14种。

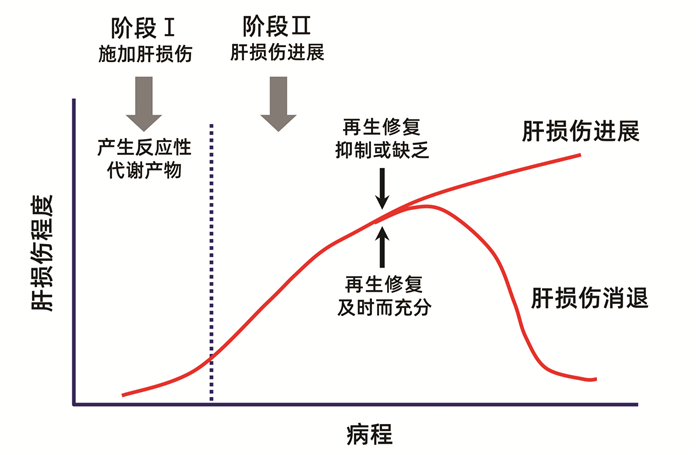

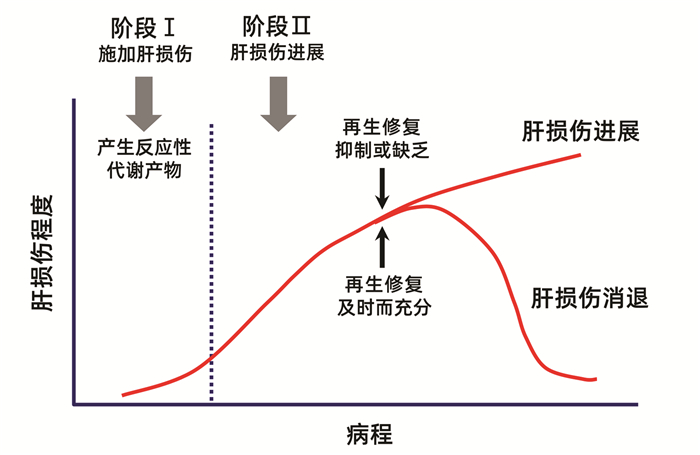

5.2 药物肝毒性进程的两阶段机制进程模型

近20年来逐渐认识到,在药物或毒物导致肝损伤后,肝细胞和肝组织能否得到及时充分的再生修复,是决定肝损伤持续加重或恢复速度的关键因素之一[21-23],并提出了两阶段模型来形象地解释这种机制(图 4)[21]。第一阶段是药物或毒物及其代谢产物通过多种机制启动和施加肝损伤。第二阶段是肝损伤发生后很快启动两个相反方向的事件。其一是肝损伤的进展和扩大,其二是迅速刺激肝细胞分裂再生和肝组织修复。肝损伤虽有进展,但若能及时启动充分的肝细胞分裂再生和组织修复,则肝损伤可以逆转。若肝细胞分裂再生和组织修复被抑制或缺乏,例如超量药物或毒物攻击时,或原有肝脏基础疾病导致肝细胞分裂再生和肝组织修复能力明显减退,则肝损伤将不断进展和加重,直至导致死亡。

在药物或其RM诱导肝损伤的过程中,致炎细胞因子TNFα也可诱导NF-κB依赖性存活基因的表达[36]。NF-κB应答基因能抑制JNK,促进抗氧化基因表达上调。同样地,氧化应激也可诱导核因子E2相关因子2,促使针对细胞应激的抗氧化基因表达上调[43]。在复杂的抗氧化系统中,起关键作用的是还原型谷胱甘肽(GSH),不仅是各种ROS的重要清除剂,也是APAP毒性代谢产物NAPQI等的清除剂,因此GSH的前体成分N-乙酰半胱氨酸可用于治疗APAP所致DILI。此外,高浓度GSH还可促进NF-κB依赖性存活基因的表达,拮抗Fas诱导的凋亡等机制,从而对细胞产生保护作用[36]。线粒体GSH的浓度也是肝细胞再生和肝组织修复的重要调节因子[44]。

再生的肝细胞是来源于成年肝细胞、肝内干细胞还是循环干细胞,目前仍存在争论。肝细胞的再生来源和再生能力,可能受到机体及肝脏的基础状况、肝损伤的原因、肝损伤的程度、肝细胞的自主信号及内分泌和旁分泌信号等多种因素的影响[45]。例如有研究[46]显示,在小鼠正常肝脏的自稳过程中,99%的新生肝细胞来源于成年肝细胞;而祖细胞在正常小鼠肝脏的自稳及再生过程中几乎不起重要作用。另有研究[47]显示,正常大鼠或代偿期肝硬化大鼠的肝细胞移植入正常受体肝脏后,能在正常微环境中立即存活并增殖;而失代偿性肝硬化大鼠的肝细胞在正常受体肝脏的微环境中起初并不扩增或产生白蛋白,但延迟2个月后其功能得以重建。

6. 总结和展望

本文系统性阐述了DILI发病的风险因素,基于发病机制的肝毒性分类及其区别与关联,不同类型肝毒性的一般性机制,从药物初始刺激到产生肝损伤效应的机制进程。全面了解这些理论及研究进展,是进一步探讨特定药物具体肝毒性的基础,有助于更好地警惕DILI风险,识别DILI相关生物标志物[48],对DILI进行科学性与个体化相结合的诊断、治疗和预防,也有助于更好地掌控新药研发的安全性。

另一方面,DILI发病机制和临床表型复杂多样,诸多问题有待进一步深入研究,诸如:(1)在真实临床场景中,由于不同个体对药物肝毒性反应存在显著差异,多数情况下很难准确把握具体药物的具体发病机制,因此需要长期的病例积累和系统研究。(2)由于影响因素和发病机制复杂,很难通过实验模型可靠地复制DILI表型和评估其发病机制,这对于药物上市前的毒理机制研究是一个巨大挑战。(3)DILI慢性化和重症化的机制。(4)DILI进展与逆转的关键“开关”或“切换”机制以及其中可能蕴含的潜在防治靶点。(5)吡咯双烷生物碱靶向于肝血窦和肝小静脉并引起肝窦阻塞综合征/肝小静脉闭塞病的机制。(6)某些药物对肝脏的致瘤或致癌机制。(7)结节性再生性增生、肉芽肿性药物性肝炎等特殊DILI表型的发病机制也需加以关注。

-

表 1 HLA遗传多态性与特定药物所致DILI的相关性

HLA基因单倍型 相关药物(患者阳性率) 相关性或对照组阳性率 A*02∶01 阿莫西林-克拉维酸 相关 A*31∶01 卡巴咪嗪(17%) 正常对照组阳性率2% A*33∶01 噻氯匹定(80%),甲基多巴(50%),依那普利(50%),

非诺贝特(43%),特比萘芬(43%),舍曲林(40%),

红霉素(20%)正常对照组阳性率1% A*33∶03 噻氯匹定 相关 B*18∶01 阿莫西林-克拉维酸 相关 B*35∶01 何首乌(41.1%) 其他原因DILI阳性率11.9% 汉族MHC数据库阳性率2.7% B*35∶02 米诺环素(16%) 正常对照组阳性率0.6% B*57∶01 氟氯西林(84%~87%) 正常对照组阳性率6% DQA1*01∶02 卢米考昔 相关 DRB1*01∶01 奈韦拉平 相关 DRB1*15∶011)/DRB5*

01∶01/DQB1*06∶02阿莫西林-克拉维酸(57%~67%)

罗美昔布

氟烷正常对照组阳性率15%~20%

强相关

强相关DRB1*07∶012)/DQB1*

02∶02/DQA1*02∶01拉帕替尼

希美加群相关

相关DRB1*16∶01/DQB1* 05∶02 氟吡汀(25%) 正常对照组阳性率1% 注:1)与药物性胆汁淤积的发生强相关; 2)可使氟氯西林诱导DILI的风险增加81~100倍以上。 表 2 三种药物肝毒性类型的比较1)

项目 固有(直接)肝毒性 特异质肝毒性 间接肝毒性 发生机制 药物及其活性代谢产物的固有(直接)肝毒性,以及人体固有的病理生理性损伤反应 与人体遗传多态性相关的特异质性药物代谢障碍,或药物-宿主蛋白加合物特异性、HLA限制性获得性免疫应答 继发于药物或其活性代谢产物的生物学活性,多通过影响免疫系统而间接对肝脏产生毒性作用 发生率 对具体药物而言,常见 对具体单药而言,少见。对药物整体而言,常见 随具体药物生物学活性特点的不同,可从少见到较为常见 剂量相关 明显的剂量依赖性 不明显(但阈剂量通常也需达到50~100 mg/d) 有一定程度的剂量和疗程相关性 可预测性 多可预测 难以预测 部分可预测 可复制性 常可在动物模型复制 难以在动物模型复制 有可能在动物模型复制 潜伏期 通常很快(数日内) 相差较大:数日至数月乃至1年以上 一般较迟出现(数月) 临床表型 肝酶升高,急性肝坏死,肝窦阻塞综合征,急性脂肪肝,结节性再生,等 急性肝细胞损伤,淤胆性肝炎,混合性肝炎,单纯性胆汁淤积,慢性肝炎,等 急性肝炎,免疫介导的肝炎,脂肪肝,慢性肝炎,等 常见涉及药物 APAP、阿司匹林、甲氨蝶呤等抗肿瘤化疗药物、高效抗逆转录病毒药物、合成代谢类甾族激素、他汀类药物、环孢霉素、肝素、丙戊酸、烟酸、丁酸、可卡因、胺碘酮、他克林、消胆胺、含有吡咯双烷生物碱的草药,等 阿莫西林-克拉维酸、氟氯西林、头孢菌素类、大环内酯类、曲伐沙星等喹诺酮类、磺胺类药物、异烟肼、吡嗪酰胺、酮康唑、特比萘芬,呋喃妥因、米诺环素,別嘌呤醇、丙基硫氧嘧啶,双氯芬酸、来氟米特、噻氯匹定、拉帕替尼、帕唑帕尼、氟他米特、他汀类药物、非诺贝特、丹曲林、胺碘酮、氟烷、托伐普坦、赖诺普利、甲基多巴、波生坦、托卡朋、苯妥英、戒酒硫、菲尔安酯,等 免疫检查点抑制剂、抗肿瘤坏死因子单抗、抗CD20单抗、蛋白激酶抑制剂、糖皮质激素、某些抗肿瘤药物、影响和干扰物质及能量代谢的相关药物,等 注:1)根据参考文献[18-19]进行必要修改。 -

[1] YU YC, MAO YM, CHEN CW, et al. CSH guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced liver injury[J]. Hepatol Int, 2017, 11(3): 221-241. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-017-9793-2. [2] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(6): 1222-1261. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.014. [3] CHALASANI NP, MADDUR H, RUSSO MW, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2021, 116(5): 878-898. DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001259. [4] DEVARBHAVI H, AITHAL G, TREEPRASERTSUK S, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: Asia Pacific Association of study of liver consensus guidelines[J]. Hepatol Int, 2021, 15(2): 258-282. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-021-10144-3. [5] BJÖRNSSON ES, BERGMANN OM, BJÖRNSSON HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(7): 1419-1425, e1-e3; quiz e19-e20. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.006. [6] TREEM WR, PALMER M, LONJON-DOMANEC I, et al. Consensus guidelines: Best practices for detection, assessment and management of suspected acute drug-induced liver injury during clinical trials in adults with chronic viral hepatitis and adults with cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B, C and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Drug Saf, 2021, 44(2): 133-165. DOI: 10.1007/s40264-020-01014-2. [7] LIU M, YANG XZ, YU YC. Current status of the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced cholestasis[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2019, 35(2): 115-120. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2019.02.003.刘梦, 杨玄子, 于乐成. 药物性胆汁淤积的发病机制及诊疗现状[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2019, 35(2): 252-257. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2019.02.003. [8] CHEN K, GUO R, WEI C. Synonymous mutation rs2515641 affects CYP2E1 mRNA and protein expression and susceptibility to drug-induced liver injury[J]. Pharmacogenomics, 2020, 21(7): 459-470. DOI: 10.2217/pgs-2019-0151. [9] CHEN R, WANG J, TANG SW, et al. CYP7A1, BAAT and UGT1A1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to anti-tuberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2016, 20(6): 812-818. DOI: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0450. [10] ZHANG M, WANG S, WILFFERT B, et al. The association between the NAT2 genetic polymorphisms and risk of DILI during anti-TB treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2018, 84(12): 2747-2760. DOI: 10.1111/bcp.13722. [11] CHANHOM N, UDOMSINPRASERT W, CHAIKLEDKAEW U, et al. GSTM1 and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms and their association with antituberculosis drug-induced liver injury[J]. Biomed Rep, 2020, 12(4): 153-162. DOI: 10.3892/br.2020.1275. [12] DALY AK, DAY CP. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of drug-induced liver injury[M]// KAPLOWITZ N, DELEVE LD. Drug-induced liver disease, 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic Press, 2013: 215-225. [13] WATKINS PB, SELIGMAN PJ, PEARS JS, et al. Using controlled clinical trials to learn more about acute drug-induced liver injury[J]. Hepatology, 2008, 48(5): 1680-1689. DOI: 10.1002/hep.22633. [14] YANG WN, PANG LL, ZHOU JY, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of HLA and polygonum multiflorum-induced liver injury in the Han Chinese population[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2020, 26(12): 1329-1339. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i12.1329. [15] YU YC, HE CL. Outcome of liver injury and liver tissue repair[J]. Chin Hepatol, 2010, 15(6): 460-464. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1704.2010.06.023.于乐成, 何长伦. 肝损伤转归与肝组织修复[J]. 肝脏, 2010, 15(6): 460-464. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1704.2010.06.023. [16] HUI CL, LEE ZJ. Hepatic disorders associated with exogenous sex steroids: MR imaging findings[J]. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2019, 44(7): 2436-2447. DOI: 10.1007/s00261-019-01941-4. [17] LU ZN, LUO Q, ZHAO LN, et al. The mutational features of aristolochic acid-induced mouse and human liver cancers[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 71(3): 929-942. DOI: 10.1002/hep.30863. [18] HOOFNAGLE JH, BJÖRNSSON ES. Drug-induced liver injury-types and phenotypes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(3): 264-273. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1816149. [19] ZHUGE Y, LIU Y, XIE W, et al. Expert consensus on the clinical management of pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 34(4): 634-642. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.14612. [20] CHEN M, BORLAK J, TONG W. A Model to predict severity of drug-induced liver injury in humans[J]. Hepatology, 2016, 64(3): 931-940. DOI: 10.1002/hep.28678. [21] MEHENDALE HM. Tissue repair: An important determinant of final outcome of toxicant-induced injury[J]. Toxicol Pathol, 2005, 33(1): 41-51. DOI: 10.1080/01926230590881808. [22] ANAND SS, MURTHY SN, VAIDYA VS, et al. Tissue repair plays pivotal role in final outcome of liver injury following chloroform and allyl alcohol binary mixture[J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2003, 41(8): 1123-1132. DOI: 10.1016/s0278-6915(03)00066-8. [23] ANAND SS, SONI MG, VAIDYA VS, et al. Extent and timeliness of tissue repair determines the dose-related hepatotoxicity of chloroform[J]. Int J Toxicol, 2003, 22(1): 25-33. DOI: 10.1080/10915810305074. [24] FONTANA RJ. Pathogenesis of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury and clinical perspectives[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(4): 914-928. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.032. [25] HOU JX, YAN FQ, YU YC. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced liver injury with extrahepatic adverse drug reactions[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2020, 36(3): 497-500. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2020.03.003.侯俊兴, 严粉琴, 于乐成. 药物性肝损伤合并肝外药物不良反应的发生机制及诊疗问题[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2020, 36(3): 497-500. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2020.03.003. [26] WANG DY, SALEM JE, COHEN JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2018, 4(12): 1721-1728. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923. [27] POSTOW MA, SIDLOW R, HELLMANN MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378(2): 158-168. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [28] VADDEPALLY RK, KHAREL P, PANDEY R, et al. Review of indications of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN guidelines with the level of evidence[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2020, 12(3): 738. DOI: 10.3390/cancers12030738. [29] PEERAPHATDIT TB, WANG J, ODENWALD MA, et al. Hepatotoxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and management recommendation[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 72(1): 315-329. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31227. [30] KOK B, LESTER E, LEE WM, et al. Acute liver failure from tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists: Report of four cases and literature review[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2018, 63(6): 1654-1666. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-018-5023-6. [31] LOPETUSO LR, MOCCI G, MARZO M, et al. Harmful effects and potential benefits of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α on the liver[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(8): 2199. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19082199. [32] ZOUBEK ME, PINAZO-BANDERA J, ORTEGA-ALONSO A, et al. Liver injury after methylprednisolone pulses: A disputable cause of hepatotoxicity. A case series and literature review[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2019, 7(6): 825-837. DOI: 10.1177/2050640619840147. [33] LOOMBA R, LIANG TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: Current concepts, management strategies, and future directions[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152(6): 1297-1309. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.009. [34] KAPILA N, AL-KHALLOUFI K, BEJARANO PA, et al. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis after kidney transplantation from HCV-viremic donors to HCV-negative recipients: A unique complication in the DAA era[J]. Am J Transplant, 2020, 20(2): 600-605. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.15583. [35] YU YC, HE CL, WANG YM. Recent progress of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis or immunosuppression-induced liver failure[J]. Infect Dis Info, 2011, 24(3): 185-188. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-8134.2011.03.018.于乐成, 何长伦, 王宇明. 纤维淤胆性肝炎/免疫抑制诱导性肝衰竭新进展[J]. 传染病信息, 2011, 24(3): 185-188. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-8134.2011.03.018. [36] RUSSMANN S, KULLAK-UBLICK GA, GRATTAGLIANO I. Current concepts of mechanisms in drug-induced hepatotoxicity[J]. Curr Med Chem, 2009, 16(23): 3041-3053. DOI: 10.2174/092986709788803097. [37] KRÄHENBUHL S, BRAUCHLI Y, KUMMER O, et al. Acute liver failure in two patients with regular alcohol consumption ingesting paracetamol at therapeutic dosage[J]. Digestion, 2007, 75(4): 232-237. DOI: 10.1159/000111032. [38] GALLUZZI L, VITALE I, AARONSON SA, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2018, 25(3): 486-541. DOI: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [39] TANG D, KANG R, BERGHE TV, et al. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death[J]. Cell Res, 2019, 29(5): 347-364. DOI: 10.1038/s41422-019-0164-5. [40] COPPLE IM, GOLDRING CE, JENKINS RE, et al. The hepatotoxic metabolite of acetaminophen directly activates the Keap1-Nrf2 cell defense system[J]. Hepatology, 2008, 48(4): 1292-1301. DOI: 10.1002/hep.22472. [41] KALGUTKAR AS, GARDNER I, OBACH RS, et al. A comprehensive listing of bioactivation pathways of organic functional groups[J]. Curr Drug Metab, 2005, 6(3): 161-225. DOI: 10.2174/1389200054021799. [42] SÉGUIN B, UETRECHT J. The danger hypothesis applied to idiosyncratic drug reactions[J]. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2003, 3(4): 235-242. DOI: 10.1097/00130832-200308000-00001. [43] WANG X, TOMSO DJ, CHORLEY BN, et al. Identification of polymorphic antioxidant response elements in the human genome[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2007, 16(10): 1188-1200. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddm066. [44] GRATTAGLIANO I, LAUTERBURG BH, PORTINCASA P, et al. Mitochondrial glutathione content determines the rate of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in eu- and hypothyroid rats[J]. J Hepatol, 2003, 39(4): 571-579. DOI: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00317-9. [45] FAUSTO N, CAMPBELL JS, RIEHLE KJ. Liver regeneration[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 57(3): 692-694. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.016. [46] MALATO Y, NAQVI S, SCHVRMANN N, et al. Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration[J]. J Clin Invest, 2011, 121(12): 4850-4860. DOI: 10.1172/JCI59261. [47] LIU L, YANNAM GR, NISHIKAWA T, et al. The microenvironment in hepatocyte regeneration and function in rats with advanced cirrhosis[J]. Hepatology, 2012, 55(5): 1529-1539. DOI: 10.1002/hep.24815. [48] YU YC, HE CL, HOU JL. Biomarkers in drug-induced liver injuries[J]. J Prac Hepatol, 2014, 17(6): 564-568. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5069.2014.06.03.于乐成, 何长伦, 侯金林. 药物诱导性肝损伤生物标志物研究进展[J]. 实用肝脏病杂志, 2014, 17(6): 564-568. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5069.2014.06.03. 期刊类型引用(25)

1. 曾雪,李福青,李清清,王红. 新型冠状病毒感染抗病毒药物引起肝损伤的发生机制. 临床肝胆病杂志. 2024(02): 402-407 .  本站查看

本站查看2. 韩世诚,王婷婷,张一昕,王茜,柴天川. 楮实子预处理对对乙酰氨基酚致L02细胞损伤的保护作用. 中国医药导报. 2024(01): 34-38 .  百度学术

百度学术3. 王宗艳,郑燕,刘如霞,李玉平,林昶,何莉华,陈云志,杨长福. 基于CiteSpace的“药物性肝损伤”研究热点与趋势分析. 贵州中医药大学学报. 2024(02): 64-69 .  百度学术

百度学术4. 孟庆霖,褚齐,宋健,董红畅,李贺,林珈羽,赵南晰. 紫苏叶总黄酮对APAP诱导的急性肝损伤的保护作用. 食品工业科技. 2024(14): 344-351 .  百度学术

百度学术5. 任晓蕾,詹轶秋,张春燕,黄琳,张晓红. 326例药物相关肝脏不良反应病例分析. 中国医院药学杂志. 2024(14): 1693-1696 .  百度学术

百度学术6. 邱倩,张慧,尹贺贺,徐洪海. 基于损伤模式建立肝再生小鼠模型的研究进展. 中华肝胆外科杂志. 2024(07): 552-556 .  百度学术

百度学术7. 陈小燕. 达格列净片致罕见急性胰腺炎及急性肝损伤1例. 中国医院药学杂志. 2024(17): 2072-2074 .  百度学术

百度学术8. 刘晨芳,张绍兵,张伟,贾敬亮. 双黄连对对乙酰氨基酚诱导大鼠肝损伤的保护作用. 兽医导刊. 2024(03): 37-39 .  百度学术

百度学术9. 廖强,韩娟,袁成雪,张瑞,李文斌,张剑. 多烯磷脂酰胆碱注射液联合异甘草酸镁注射液治疗药物性肝损伤的效果. 西北药学杂志. 2024(06): 149-153 .  百度学术

百度学术10. 王宇,黄婧怡,侯立新,李爽,崔永康,黄兰蔚. 社区获得性肺炎患者抗生素相关性肝损伤外周血体液免疫特点分析. 中国药物警戒. 2023(02): 132-135+139 .  百度学术

百度学术11. 程军,韩一萱,汪龙,朱玲娜. 克唑替尼相关肝损伤研究进展. 药物不良反应杂志. 2023(02): 107-111 .  百度学术

百度学术12. 张婷,冯石卜,姜祎,张化为,宋小妹,张东东,李玉泽,黄文丽,邓翀. 山茱萸果核提取物不同洗脱部位对急性药物性肝损伤的作用研究. 中南药学. 2023(03): 652-656 .  百度学术

百度学术13. 朱蓉蓉,谢治强,马瑞萍. 药物性肝损伤研究现状. 社区医学杂志. 2023(10): 535-539 .  百度学术

百度学术14. 于乐成,郝坤艳,范晔. 中草药肝损伤的临床诊断. 中国药物警戒. 2023(05): 481-488 .  百度学术

百度学术15. 彭小蓉,常宇南,秦涛,商婷婷,许红梅. 儿童药物性肝损伤临床诊治进展. 中华肝脏病杂志. 2023(04): 440-444 .  百度学术

百度学术16. 张虹,金艳蕾,唐君. 疑似联合用药导致药物性肝损伤1例的诊治分析. 中国社区医师. 2023(16): 52-54 .  百度学术

百度学术17. 陈凡,刘剑敏,胡述立,张韶辉. 低白蛋白血症与卡泊芬净导致肝损伤相关性的回顾性队列研究. 药物不良反应杂志. 2023(07): 419-423 .  百度学术

百度学术18. 许波,王勤英. 药物性肝损伤202例临床特征分析. 中国基层医药. 2023(08): 1189-1193 .  百度学术

百度学术19. 马丹彤,段雪飞. 药物性肝损伤的诊治进展. 中华全科医师杂志. 2023(11): 1204-1209 .  百度学术

百度学术20. 李银,孙会静,刘跃琼,古正祥,刘正德. 疑似头孢曲松致儿童肝损伤报道1例. 妇儿健康导刊. 2023(20): 73-75 .  百度学术

百度学术21. 赖荣陶,于乐成,陈成伟. 2021药物性肝损伤研究回顾和临床关注的问题. 肝脏. 2022(01): 1-3 .  百度学术

百度学术22. 聂晓璐,彭亚光,孙子墨,彭晓霞. 药物性肝损伤诊断相关生化指标阈值制定的研究现状及思考. 中国药物警戒. 2022(03): 244-247+258 .  百度学术

百度学术23. 詹淑华,赵慧姝,陈贵儒. 预防性保肝治疗对老年初治肺结核患者肝损伤的影响研究. 医学信息. 2022(14): 45-48 .  百度学术

百度学术24. 严微,黄会芳. 糖皮质激素治疗重症药物性肝损伤的效果分析. 临床肝胆病杂志. 2022(10): 2302-2307 .  本站查看

本站查看25. 崔今姬,金京哲,穆振斌. 化疗药物对胃肠道恶性肿瘤患者肝损伤的影响因素分析. 社区医学杂志. 2022(19): 1100-1106 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(10)

-

PDF下载 ( 4898 KB)

PDF下载 ( 4898 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术