Effect of polarized bone marrow-derived macrophage transplantation on the progression of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats

-

摘要:

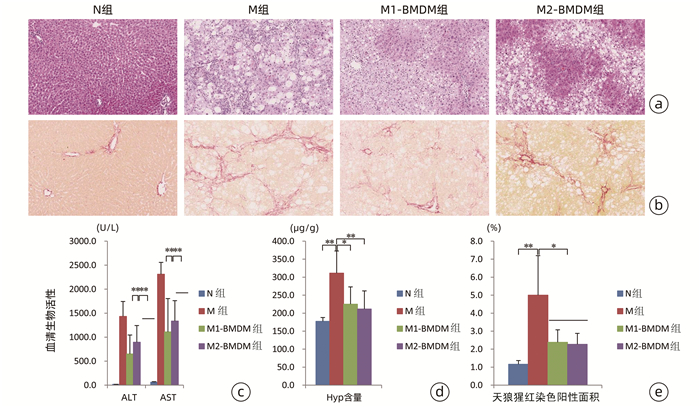

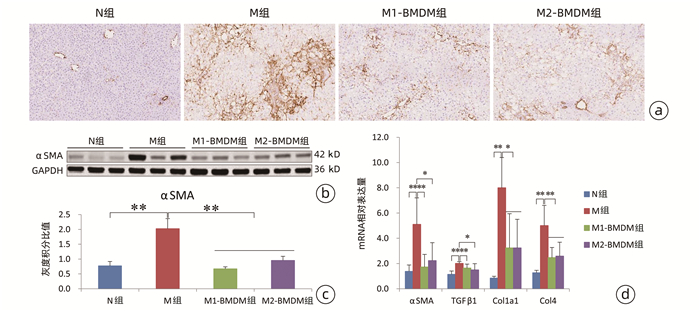

目的 观察极化骨髓巨噬细胞(BMDM)移植对CCl4诱导实验大鼠模型肝纤维化进展的影响。 方法 分离大鼠BMDM,分别使用脂多糖(5 ng/mL)诱导其分化为M1(M1-BMDM)表型,L929细胞上清诱导其分化为M2(M2-BMDM)表型。以30% CCl4皮下注射6周建立大鼠肝纤维化模型,于第7周开始模型大鼠随机分为模型对照组(M)、M1-BMDM组和M2-BMDM组,分别予以生理盐水、M1-BMDM、M2-BMDM经尾静脉一次性注射,并以30% CCl4持续造模至第9周末。观察肝功能、肝组织病理、肝组织羟脯氨酸(Hyp)含量、肝星状细胞活化、肝纤维化及炎症相关细胞因子表达水平等。计量资料采用x±s表示,多组间比较采用方差分析,进一步两两比较采用SNK-q检验。 结果 与M组相比,M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM均可明显抑制肝脏炎症反应和肝纤维化进展,显著降低血清ALT、AST活性(P值均<0.01),显著降低肝组织Hyp含量(P值均<0.05)。M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM可显著抑制肝星状细胞活化,显著降低肝纤维化相关因子TGFβ、Col1a1、Col4 mRNA表达水平(P值均<0.05)。M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM均可显著提高肝组织CD163蛋白表达水平(P值均<0.01),且M2-BMDM组显著高于M1-BMDM组(P<0.05);两者均可显著降低肝组织MMP-2和TIMP-1 mRNA表达水平(P值均<0.05),显著提高MMP-13 mRNA表达水平(P值均<0.01);且M2-BMDM可显著降低肝组织CD68蛋白表达水平(P<0.01)。M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM均可显著提高肝组织IL-6和IL-10 mRNA以及白蛋白表达水平(P值均<0.05),且M2-BMDM组以上指标均显著高于M1-BMDM组(P值均<0.05)。 结论 M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM均可有效抑制CCl4诱导大鼠肝纤维化进展,其共同机制可能与抑制肝星状细胞活化、促进抗炎巨噬细胞活化有关; 且M2-BMDM还可抑制促炎巨噬细胞活化,综合干预效应优于M1-BMDM。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the effect of polarized bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) transplantation on the progression of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Methods Rat BMDMs were isolated and induced to differentiate into M1 phenotype (M1-BMDM) by lipopolysaccharide (5 ng/mL) or M2 phenotype (M2-BMDM) by the supernatant of L929 cells. A rat model of liver fibrosis was established by subcutaneous injection of 30% CCl4 for 6 weeks, and at week 7, the model rats were randomly divided into model control group (M group), M1-BMDM group, and M2-BMDM group and were given a single injection of normal saline, M1-BMDM, and M2-BMDM, respectively, via the caudal vein, and subcutaneous injection of 30% CCl4 was given until the end of week 9. Related indices were observed, including liver function, liver histopathology, hydroxyproline (Hyp) content in liver tissue, hepatic stellate cell activation, liver fibrosis, and expression of inflammatory cytokines. The continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation; an analysis of variance was used for comparison between multiple groups, and the SNK-q test was used for further comparison between two groups. Results Compared with the M group, both M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM significantly inhibited liver inflammation and liver fibrosis progression and significantly reduced serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities (P < 0.01) and Hyp content in liver tissue (P < 0.05). M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM significantly inhibited the activation of hepatic stellate cells and significantly reduced the mRNA expression levels of TGF-β, Col1A1, and Col4 (all P < 0.05). Both M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM significantly increased the expression level of CD163 protein in liver tissue (P < 0.01), and the M2-BMDM group had a significantly higher level than the M1-BMDM group (P < 0.05); both M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM significantly reduced the mRNA expression levels of MMP-2 and TIMP-1 in liver tissue (P < 0.05) and significantly increased the mRNA expression level of MMP-13 (P < 0.01); in addition, M2-BMDM significantly reduced the expression level of CD68 protein in liver tissue (P < 0.01). Both M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM significantly increased the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 and IL-10 and the protein expression level of albumin in liver tissue (all P < 0.05), and the above indices in the M2-BMDM group were significantly higher than those in the M1-BMDM group (all P < 0.05). Conclusion Both M1-BMDM and M2-BMDM can effectively inhibit the progression of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats, possibly by inhibiting the activation of hepatic stellate cells and promoting the activation of anti-inflammatory macrophages. Moreover, M2-BMDM can also inhibit the activation of pro-inflammatory macrophages and thus has a better comprehensive intervention effect than M1-BMDM. -

Key words:

- Liver Cirrhosis /

- Hepatic Stellate Cells /

- Macrophages

-

注:a,M1-BMDM CD11b/c免疫荧光染色(×600);b,M1-BMDM CD68免疫荧光染色(×600);c,M2-BMDM CD206免疫荧光染色(×600); d,M2-BMDM CD163免疫荧光染色(×600); e,M1-BMDM细胞流式细胞鉴定; f,M2-BMDM细胞流式细胞鉴定, 在进行FACS检验的样本细胞中, 93.1%是单一且唯一的细胞群, 这群细胞中CD206+细胞占比为98.9%, CD68+细胞占比为10.8%; g,N组、M1-BMDM组和M2-BMDMCD206组CD68 mRNA的表达水平(n=3),* *P<0.01。

图 1 M1-BMDM和M2-BMDM鉴定

-

[1] RAMACHANDRAN P, DOBIE R, WILSON-KANAMORI JR, et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level[J]. Nature, 2019, 575(7783): 512-518. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1631-3. [2] KARLMARK KR, WEISKIRCHEN R, ZIMMERMANN HW, et al. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis[J]. Hepatology, 2009, 50(1): 261-274. DOI: 10.1002/hep.22950. [3] VANNELLA KM, WYNN TA. Mechanisms of organ injury and repair by macrophages[J]. Annu Rev Physiol, 2017, 79: 593-617. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034356. [4] ORECCHIONI M, GHOSHEH Y, PRAMOD AB, et al. Macrophage polarization: Different gene signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. classically and M2(LPS-) vs. alternatively activated macrophages[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 1084. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01084. [5] MURRAY PJ, ALLEN JE, BISWAS SK, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: Nomenclature and experimental guidelines[J]. Immunity, 2014, 41(1): 14-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [6] DAVIS BK. Derivation of macrophages from mouse bone marrow[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2019, 1960: 41-55. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9167-9_3. [7] WATANABE Y, TSUCHIYA A, SEINO S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and induced bone marrow-derived macrophages synergistically improve liver fibrosis in mice[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2019, 8(3): 271-284. DOI: 10.1002/sctm.18-0105. [8] PINEDA-TORRA I, GAGE M, de JUAN A, et al. Isolation, culture, and polarization of murine bone marrow-derived and peritoneal macrophages[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2015, 1339: 101-109. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2929-0_6. [9] MILY A, KALSUM S, LORETI MG, et al. Polarization of M1 and M2 human monocyte-derived cells and analysis with flow cytometry upon mycobacterium tuberculosis infection[J]. J Vis Exp, 2020, (163). DOI: 10.3791/61807. [10] JAMALL IS, FINELLI VN, QUE HEE SS. A simple method to determine nanogram levels of 4-hydroxyproline in biological tissues[J]. Anal Biochem, 1981, 112(1): 70-75. DOI: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90261-x. [11] MU YP, OGAWA T, KAWADA N. Reversibility of fibrosis, inflammation, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the liver of rats fed a methionine-choline-deficient diet[J]. Lab Invest, 2010, 90(2): 245-256. DOI: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.123. [12] PRADERE JP, KLUWE J, DE MINICIS S, et al. Hepatic macrophages but not dendritic cells contribute to liver fibrosis by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells in mice[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 58(4): 1461-1473. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26429. [13] HUME DA, IRVINE KM, PRIDANS C. The mononuclear phagocyte system: The relationship between monocytes and macrophages[J]. Trends Immunol, 2019, 40(2): 98-112. DOI: 10.1016/j.it.2018.11.007. [14] MA PF, GAO CC, YI J, et al. Cytotherapy with M1-polarized macrophages ameliorates liver fibrosis by modulating immune microenvironment in mice[J]. J Hepatol, 2017, 67(4): 770-779. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.022. [15] FRIEDMAN SL. Hepatic stellate cells: Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver[J]. Physiol Rev, 2008, 88(1): 125-172. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [16] NOVO E, MARRA F, ZAMARA E, et al. Dose dependent and divergent effects of superoxide anion on cell death, proliferation, and migration of activated human hepatic stellate cells[J]. Gut, 2006, 55(1): 90-97. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.069633. [17] RAMACHANDRAN P, IREDALE JP. Macrophages: Central regulators of hepatic fibrogenesis and fibrosis resolution[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 56(6): 1417-1419. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.026. [18] FENG M, DING J, WANG M, et al. Kupffer-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 contributes to liver fibrosis resolution[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2018, 14(9): 1033-1040. DOI: 10.7150/ijbs.25589. [19] GUO J, LUO Y, YIN F, et al. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-like ligand 1 A in myeloid cells aggravates liver fibrosis in mice[J]. J Immunol Res, 2019, 2019: 7657294. DOI: 10.1155/2019/7657294. [20] GORDON S, MARTINEZ FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: Mechanism and functions[J]. Immunity, 2010, 32(5): 593-604. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [21] TAO Y, WANG M, CHEN E, et al. Liver Regeneration: Analysis of the main relevant signaling molecules[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2017, 2017: 4256352. DOI: 10.1155/2017/4256352. [22] CRESSMAN DE, GREENBAUM LE, DEANGELIS RA, et al. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice[J]. Science, 1996, 274(5291): 1379-1383. DOI: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [23] TAUB R. Liver regeneration: From myth to mechanism[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2004, 5(10): 836-847. DOI: 10.1038/nrm1489. [24] KANG LI, MARS WM, MICHALOPOULOS GK. Signals and cells involved in regulating liver regeneration[J]. Cells, 2012, 1(4): 1261-1292. DOI: 10.3390/cells1041261. [25] ELCHANINOV AV, FATKHUDINOV TK, VISHNYAKOVA PA, et al. Phenotypical and functional polymorphism of liver resident macrophages[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(9): 1032-1053. DOI: 10.3390/cells8091032. [26] CAMPANA L, ESSER H, HUCH M, et al. Liver regeneration and inflammation: From fundamental science to clinical applications[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021, 22(9): 608-624. DOI: 10.1038/s41580-021-00373-7. [27] BARBAY V, HOUSSARI M, MEKKI M, et al. Role of M2-like macrophage recruitment during angiogenic growth factor therapy[J]. Angiogenesis, 2015, 18(2): 191-200. DOI: 10.1007/s10456-014-9456-z. [28] DONG X, LIU J, XU Y, et al. Role of macrophages in experimental liver injury and repair in mice[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2019, 17(5): 3835-3847. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7450. 期刊类型引用(2)

1. 王晓迪,周帆,莫秋萍,赵艳娟. 血小板凝集功能、纤维蛋白原水平与急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死患者经皮冠状动脉介入术后发生主要不良心脏事件相关性分析. 临床军医杂志. 2023(03): 301-303+307 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 邹海虹,林宇,白云雪,聂益军. 不同泌尿外科疾病凝血及血小板参数指标的对比研究. 实验与检验医学. 2023(06): 761-763+768 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(0)

-

PDF下载 ( 6875 KB)

PDF下载 ( 6875 KB)

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术