免疫检查点抑制剂抗肿瘤治疗与HBV再激活的关系

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.06.027

Association between immune checkpoint inhibitor antitumor therapy and hepatitis B virus reactivation

-

摘要: 近年来,免疫检查点抑制剂(ICI)单药和联合治疗在从实体瘤到淋巴瘤等多种恶性肿瘤中取得了广泛的疗效,并且成为了多种癌症的标准化和系统化治疗模式。然而,在HBV感染的恶性肿瘤患者中,ICI应用的安全性研究尚不多见。有早期研究陆续报道在临床中ICI抗肿瘤治疗所致的HBV再激活。本文通过回顾已有文献,对近年来ICI在慢性病毒感染的癌症患者中的临床试验及应用进展进行综述,阐明这类特殊群体应用ICI的有效性及安全性,以期为临床用药提供一定参考。Abstract: In recent years, monotherapy and combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have achieved good efficacy in a variety of malignancies from solid tumors to lymphomas and have become a standardized and systematic treatment modality for many cancers. However, there is still a lack of studies on the safety of ICIs in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients with malignancies, and early studies have reported HBV reactivation due to ICI antitumor therapy in clinical practice. With reference to related literature, this article reviews the recent clinical trials and application of ICIs in cancer patients with chronic viral infection and clarifies the efficacy and safety of ICIs in this special population, in order to provide a reference for clinical medication.

-

Key words:

- Liver Neoplasms /

- Hepatitis B, Chronic /

- Reinfection /

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

-

近年来以免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitors,ICI)为代表的免疫治疗以其良好的安全性和令人鼓舞的客观反应性使肿瘤的治疗发生了革命性的转变,为许多晚期癌症患者治疗提供了新的机遇,同时也被批准成为了多种癌症标准化治疗的一线或二线用药[1]。此外,基于不断更新的肿瘤免疫治疗指南,ICI的适应证也在不断扩大,越来越多的癌症患者将接触到这类药物[2]。HBV感染是世界范围内的一个主要健康问题,现有治疗方法无法根除它[3]。尽管在免疫功能正常的成年人中,只有不到5%的人发展为持续性感染即慢性乙型肝炎(CHB),但大多数在婴儿期或儿童早期获得的感染会变成CHB[4]。然而在大多数免疫疗法的关键临床试验中,由于对ICI的疗效、毒性和病毒再激活风险的担忧,既往存在慢性HBV感染的癌症患者通常被排除在外。缺乏关于在慢性病毒感染的癌症患者中使用ICI治疗的前瞻性、大规模数据,使得ICI在这类特殊人群中的临床应用缺少高级别临床证据支持,限制了基于证据的治疗决策。因此,本文总结了目前关于ICI治疗期间HBV再激活风险的现有临床试验及其可能存在机制,并提出了针对性预防和治疗策略,以期为此类特殊群体的临床治疗提供参考。

1. HBV再激活的定义及危险因素

HBV再激活(hepatitis B virus reactivation,HBVr)是指处于CHB非活动期患者或既往HBV感染者活动性肝炎的复发。不同指南对HBVr定义有所不同,但一般原则相似(表 1)。导致HBVr风险因素众多,其大致可分为三种类型:宿主相关因素、病毒相关因素和药物相关因素[5]。

表 1 不同指南对HBVr的定义Table 1. Definitions of HBV reactivation in different guidelines指南 CHB患者HBVr 既往HBV感染者HBVr 满足以下任何一项可诊断 满足以下任何一项可诊断 美国胃肠病学会(AGA)2015年指南 ·在无法获得的DNA基线水平的患者中:没有明确的定义

·可获得的DNA基线,以前检测不到的患者中:新的可检测的DNA

·可获得的DNA基线水平,以前可以检测到患者中:≥10倍的增长·反向血清转换,HBsAg阳性状态 亚太肝病学会(APASL)2016年指南 ·不可获得DNA基线水平的患者中:≥20 000 IU/mL

·可获得DNA基线,以前检测不到的患者中:重新检测HBV DNA到100 IU/mL的水平

·可获得DNA基线,以前可检测到的:比基线水平增加≥2 lg·未明确的定义 欧洲肝病学会(EASL)2017年指南 ·未明确的定义 ·未明确的定义 美国肝病学会(AASLD)2018年指南 ·在无法获得HBV DNA基线水平的患者中≥10 000 IU/mL

·可获得DNA基线水平,在以前未检测的患者中≥1 000 IU/mL

·可检测的DNA基线水平,以前可以检测患者中≥100倍的增加·进展为可检测到的DNA ·HBsAg的重新出现(也称为反向血清转换) 韩国肝病学会(KASL)2019年指南 ·血清HBV DNA增加超过基线水平的100倍 ·HBsAg阴性血清转换为阳性·检测血清HBV DNA从无到阳性 中华医学会感染病学/肝病学分会2019年指南 ·HBsAg阳性/抗-HBc阳性,或HBsAg阴性/抗-HBc阳性患者接受免疫抑制治疗

或化学治疗时,HBV DNA较基线升高≥2 lgIU/mL或基线HBV DNA阴性者转为阳性,或HBsAg由阴性转为阳性·未明确的定义 美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)2020年指南 ·与AASLD指南相同 ·与AASLD指南相同 宿主因素:在以往的研究[6]中,年龄较大和男性被认为是HBVr的危险因素。此外,有研究[7-8]显示,既往存在基础疾病和需要免疫抑制治疗的患者也是HBVr的一个重要因素。综上,宿主免疫力低下是HBVr的一个重要风险因素。病毒学因素:无论HBsAg阳性或HBV DNA状态如何,HBV感染都会在肝细胞中引起共价封闭的环状DNA(cccDNA),cccDNA在受感染的细胞中非常稳定,可以在潜伏状态下持续存在,这是HBVr的关键驱动因素[9]。Asai等[10]发现,HBsAg阳性、HBeAg阳性和免疫抑制治疗前高HBV DNA水平也是HBVr的危险因素。此外,HBsAg的突变也可能是HBVr的一个新问题。药物因素:不同的免疫抑制药物在HBVr中具有不同的风险特征。最近的大规模前瞻性研究[11]报道了恶性淋巴瘤的利妥昔单抗方案治疗下HBV感染已经恢复的患者中HBVr的发生。此外,2016年欧洲肿瘤内科学会报道了肿瘤药物如蒽环类药物、长春花碱、甲氨蝶呤、环磷酰胺、依托泊苷和依维莫司等与高HBVr发生率有关,并建议在任何系统性抗癌治疗开始前进行HBV筛查和启动适当的抗病毒预防[12]。2021年亚太肝病APASL指南根据宿主因素、病毒学因素及免疫抑制剂药物种类、剂量因素,将HBVr风险分为高风险(HBVr率 > 10%)、中风险(HBVr率1%~10%)和低风险(HBVr率 < 1%)[13]。然而,区别于化疗和传统免疫抑制剂诱发的HBVr,ICI导致的HBVr的具体机制尚不明确,因此,随着更多以细胞程序性死亡受体1及其配体(programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death-ligand 1,PD-1/PD-L1)抑制剂为代表的ICI新药进入临床领域,它们对HBV合并癌症患者的影响需要进行更深入探究。

2. ICI在HBVr中的双重作用

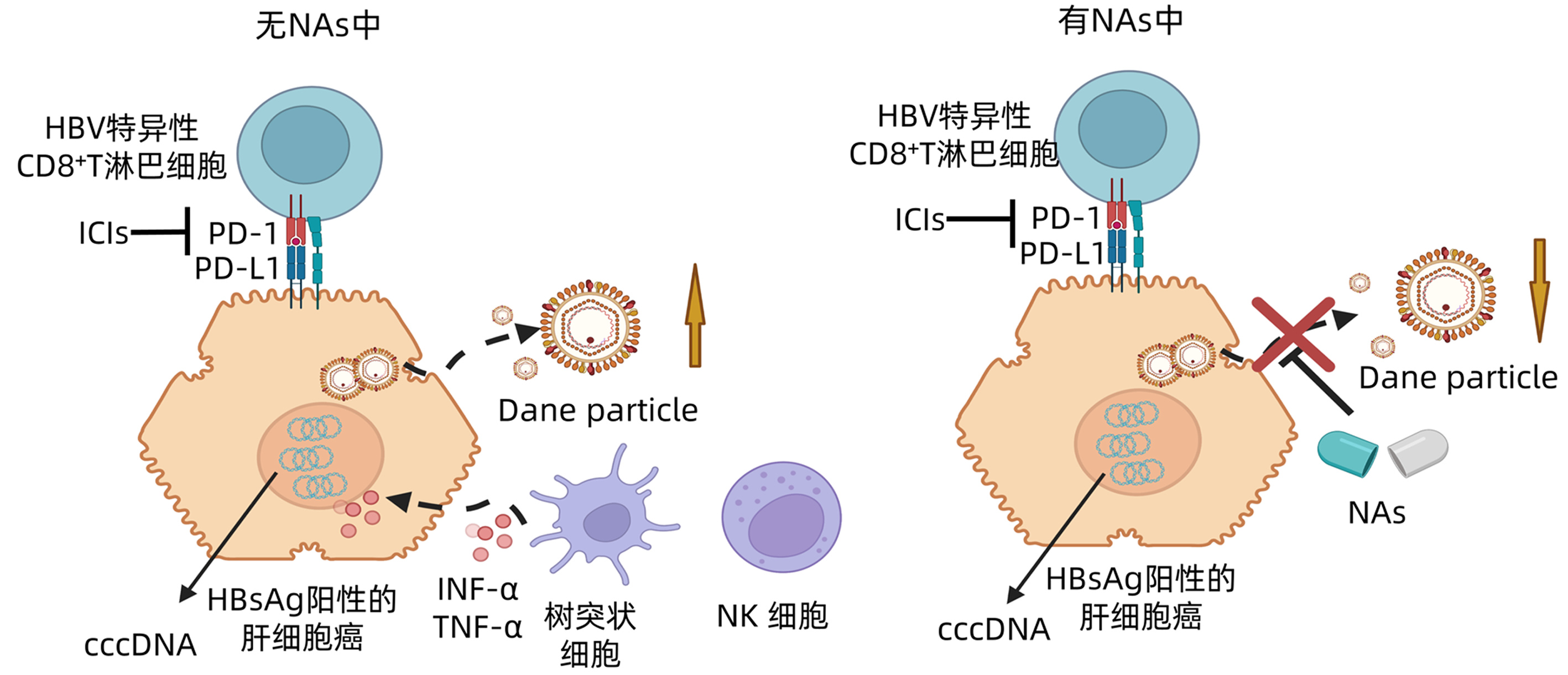

ICI治疗已成为HBV感染者的一把双刃剑——它既可导致肝脏不良事件或HBVr,也可使得HBV感染者功能性治愈。最近研究[14]表明,在ICI治疗中,不平衡的免疫系统和通过检查点抑制释放T淋巴细胞介导的细胞毒性可能会导致HBV或其他预先存在的慢性感染(如HCV、结核病)的重新激活。此外,越来越多的证据表明,慢性HBV感染与肿瘤细胞上的PD-L1表达密切相关,表明了病毒对系统性免疫反应的调解作用[15]。目前,少数病例报告表明,在免疫治疗期间,CHB患者甚至是HBV感染已治愈的患者都可能发生HBVr,但具体机制尚不清楚[16]。研究[17]显示,PD-1/PD-L1轴是维持免疫平衡的一个重要途径,除了参与癌症免疫逃逸外,在HBV感染过程中也起作用。HBV感染是一个动态过程,反映了HBV复制和宿主免疫反应之间的互动[18]。一方面,HBV通过激发CD8+T淋巴细胞过度表达负性共刺激分子(如PD-1、CTLA4、LAG-3等),诱导CD8+T淋巴细胞衰竭以逃避免疫破坏,阻断这些共刺激途径已显示出病毒负荷的显著降低[19]。因此,ICI治疗可通过阻断PD-1/PD-L1的接合可以部分恢复其抗病毒功能[20]。另一方面,慢性HBV感染者的特点是疲惫的T淋巴细胞群,在慢性HBV感染期间,其病毒特异性T淋巴细胞反应较弱,阻碍了病毒的清除和肝炎的恢复[21]。此外,PD-1作为一种重要的免疫抑制介质,阻断PD-1/PD-L1轴可能会导致肝细胞的破坏和以前潜伏的病毒释放到循环中。当ICI被用于HBsAg阳性肿瘤患者而不使用核苷酸类似物(NAs)时,可发生HBVr和肝功能障碍,而使用NAs能抑制该过程的发生(图 1)。Kumagai等[22]研究也证实了效应性T淋巴细胞和调节性T淋巴细胞之间的PD-1表达平衡在PD-1阻断疗法临床疗效中的预示作用。此外,当调节性T淋巴细胞上PD-1表达量高于CD8+T淋巴细胞上的PD-1表达量时,抗肿瘤效果会因由此产生的免疫耐受而减弱。因此,有学者[23]建议对于CHB合并肿瘤患者,在使用ICI抗肿瘤治疗前预先使用NAs来防止HBVr。当前,仍然需要更多的基础研究来揭示ICI治疗导致的HBVr的潜在机制。

3. ICI治疗期间HBVr的临床研究

对于HBsAg阳性并接受化疗药物的癌症患者来说,需要进行抗病毒预防和密切监测HBVr的共识已经确立,但ICI在这类群体中的安全性研究甚少[25]。在CheckMate 040研究[24]中,15例HBV感染的肝细胞癌患者接受了纳武单抗治疗,未出现HBVr,但这些患者在治疗前被要求接受有效的抗病毒治疗,并且在筛查时病毒载量低于100 IU/mL。在KEYNOTE-224研究[25]中,22例HBV合并晚期肝细胞癌患者接受了派姆单抗治疗,没有报道HBVr,但这些患者在接受ICI治疗前也被要求抗病毒治疗使病毒载量低于100 IU/mL。尽管以上临床试验并未报告在治疗中HBVr,但在纳入的人群中,患者在接受首剂ICI治疗前都被要求接受NAs治疗,且病毒载量 < 100 IU/mL。然而,现实生活中,ICI治疗的患者群体比临床试验中更复杂,这就提出了一个问题,即在ICI治疗前保持低病毒载量的必要性。Zhang等[16]在114例HBsAg阳性、接受抗PD-1/PD-L1抗体治疗癌症的患者队列研究中评估HBVr,有6例(5.3%)患者在ICI开始后发生HBVr,中位发病时间为18周(范围为3~35周),缺乏抗病毒预防措施可能是HBVr的唯一重要风险因素。最近,Pu等[26]在关于ICI在晚期癌症合并既往HBV和/或HCV感染者中使用情况进行系统性文献回顾分析,共纳入了186例患者,在89例CHB患者中,有67例未同时接受抗病毒治疗,除了2例(2.8%)患者出现HBV载量升高,7例(10.4%)患者出现降低,大多数患者在治疗期间没有出现HBV载量变化。目前已完成的关键性的临床研究评估免疫治疗与HBVr发生的风险见附录A。上述已发表的HBV合并恶性肿瘤患者ICI治疗的关键性临床研究数据表明,在此类患者中ICI治疗总体上是安全有效的,HBV感染不应成为ICI治疗的禁忌证。此外,鉴于少部分慢性HBV感染者存在一定的再激活的风险,因此有必要在ICI治疗前进行HBsAg和抗-HBc的普遍筛查。对于血清HBsAg阳性的患者,无论基线HBV DNA水平如何,都建议开始预防性抗病毒治疗,而对于已治愈的HBV感染者,建议仔细监测血清ALT和HBV DNA[27]。然而,对于检测结果为阳性的患者,目前还不清楚预防性治疗应该持续多长时间,考虑到ICI的持久效果超过其用药期,以及HBVr多发生于治疗晚期,因此,抗病毒治疗应在最后一剂ICI后至少持续6个月,即使在HBV DNA阴性后也不能停止[28]。在HBVr发生后开始抗HBV治疗已被证明不如预防或预防性治疗有效,因此,所有CHB患者应考虑进行初级预防。但是,目前仍缺乏高质量数据用于该类特殊患者ICI治疗的临床指导,而正在进行的大规模的临床试验可能会进一步回答这个问题(表 2)。

表 2 正在进行的ICI抗癌症患者中HBVr的临床试验Table 2. Ongoing clinical trial of ICI against HBV reactivation in cancer patients临床试验号 例数 疾病 ICI 临床试验分期 研究内容 NCT04680598 800 肝细胞癌合并HBsAg阳性患者 纳武单抗

特瑞普利单抗

派姆单抗

信迪利单抗

卡瑞利珠单抗

阿替利珠单抗- 低HBV DNA载量和高HBV DNA载量患者在接受抗病毒预防和ICI时的HBVr情况 NCT04180072 48 局部晚期或转移性和/或不能切除的肝细胞癌合并HBsAg阳性患者 阿替利珠单抗 - ICI联合蛋白激酶B抑制剂治疗晚期肝癌和慢性HBV感染所致的肝癌的总有效率及HBVr情况 NCT04294498 43 肝细胞癌合并HBsAg且HBV DNA≥2 000 IU/mL 度伐利尤单抗 Ⅱ 评估在度伐利尤单抗治疗中HBVr情况 NCT01658878 1 100 未感染的肝细胞癌受试者,HCV感染的肝细胞癌受试者和HBV感染的受试者 纳武单抗

伊匹木单抗Ⅰ、Ⅱ 用于评估尼武单抗或尼武单抗与其他药物联合使用在HBV、HCV合并晚期肝细胞癌患者中的有效性、安全性和耐受性 4. 总结与展望

目前,来自病例报告、回顾性队列研究等小型的临床试验有限数据初步证实了ICI在HBV感染的恶性肿瘤患者中的安全性。然而,对这一特殊亚群的整体肿瘤管理仍有许多担忧,ICI应用于这类特殊人群中还存在着一些临床问题需要前瞻性解决。首先,既往研究的局限性,缺乏高质量临床数据,需要进一步大样本的研究以验证结果。其次,当前HBV感染者ICI治疗安全性研究主要包括有限类型的恶性肿瘤患者,如黑色素瘤、肺癌和肝细胞癌,或者只关注ICI治疗,而随着ICI越来越多地适用于多种恶性肿瘤,并倾向于与细胞毒性药物或分子靶向药物同时使用,在这些中的安全性还有待进一步论证。此外,基于肿瘤异质性,不同肿瘤患者接受ICI治疗发生HBVr的机制是否可主要归因于PD-1/PD-L1轴的作用还有待进一步证实。当前,关于ICI引起HBVr的特点、频率和时间尚不明确,最佳抗HBV治疗时机和疗程等也不确定,这些都需要进一步去研究解决。尽管既往研究表明,缺乏预防性抗病毒治疗是HBVr的一个重要风险因素,但其机制仍不清楚。最后,HBV感染如何影响癌症患者的全身免疫反应和ICI的作用也应进一步研究。考虑到以上的局限性,需要进一步前瞻性、大样本的临床试验以确定ICI所致HBVr的风险因素,并优化接受ICI治疗的癌症患者HBVr的预防和管理,以促进ICI在更广泛的患者群体中更安全、有效的使用。

-

表 1 不同指南对HBVr的定义

Table 1. Definitions of HBV reactivation in different guidelines

指南 CHB患者HBVr 既往HBV感染者HBVr 满足以下任何一项可诊断 满足以下任何一项可诊断 美国胃肠病学会(AGA)2015年指南 ·在无法获得的DNA基线水平的患者中:没有明确的定义

·可获得的DNA基线,以前检测不到的患者中:新的可检测的DNA

·可获得的DNA基线水平,以前可以检测到患者中:≥10倍的增长·反向血清转换,HBsAg阳性状态 亚太肝病学会(APASL)2016年指南 ·不可获得DNA基线水平的患者中:≥20 000 IU/mL

·可获得DNA基线,以前检测不到的患者中:重新检测HBV DNA到100 IU/mL的水平

·可获得DNA基线,以前可检测到的:比基线水平增加≥2 lg·未明确的定义 欧洲肝病学会(EASL)2017年指南 ·未明确的定义 ·未明确的定义 美国肝病学会(AASLD)2018年指南 ·在无法获得HBV DNA基线水平的患者中≥10 000 IU/mL

·可获得DNA基线水平,在以前未检测的患者中≥1 000 IU/mL

·可检测的DNA基线水平,以前可以检测患者中≥100倍的增加·进展为可检测到的DNA ·HBsAg的重新出现(也称为反向血清转换) 韩国肝病学会(KASL)2019年指南 ·血清HBV DNA增加超过基线水平的100倍 ·HBsAg阴性血清转换为阳性·检测血清HBV DNA从无到阳性 中华医学会感染病学/肝病学分会2019年指南 ·HBsAg阳性/抗-HBc阳性,或HBsAg阴性/抗-HBc阳性患者接受免疫抑制治疗

或化学治疗时,HBV DNA较基线升高≥2 lgIU/mL或基线HBV DNA阴性者转为阳性,或HBsAg由阴性转为阳性·未明确的定义 美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)2020年指南 ·与AASLD指南相同 ·与AASLD指南相同 表 2 正在进行的ICI抗癌症患者中HBVr的临床试验

Table 2. Ongoing clinical trial of ICI against HBV reactivation in cancer patients

临床试验号 例数 疾病 ICI 临床试验分期 研究内容 NCT04680598 800 肝细胞癌合并HBsAg阳性患者 纳武单抗

特瑞普利单抗

派姆单抗

信迪利单抗

卡瑞利珠单抗

阿替利珠单抗- 低HBV DNA载量和高HBV DNA载量患者在接受抗病毒预防和ICI时的HBVr情况 NCT04180072 48 局部晚期或转移性和/或不能切除的肝细胞癌合并HBsAg阳性患者 阿替利珠单抗 - ICI联合蛋白激酶B抑制剂治疗晚期肝癌和慢性HBV感染所致的肝癌的总有效率及HBVr情况 NCT04294498 43 肝细胞癌合并HBsAg且HBV DNA≥2 000 IU/mL 度伐利尤单抗 Ⅱ 评估在度伐利尤单抗治疗中HBVr情况 NCT01658878 1 100 未感染的肝细胞癌受试者,HCV感染的肝细胞癌受试者和HBV感染的受试者 纳武单抗

伊匹木单抗Ⅰ、Ⅱ 用于评估尼武单抗或尼武单抗与其他药物联合使用在HBV、HCV合并晚期肝细胞癌患者中的有效性、安全性和耐受性 -

[1] KONG X, LU P, LIU C, et al. A combination of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: The prospect of overcoming the weakness of tumor immunotherapy (Review)[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2021, 23(5): 362. DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12001. [2] HASLAM A, GILL J, PRASAD V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2020, 3(3): e200423. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0423. [3] SHI Y, ZHENG M. Hepatitis B virus persistence and reactivation[J]. BMJ, 2020, 370: m2200. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m2200. [4] YUEN MF, CHEN DS, DUSHEIKO GM, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2018, 4: 18036. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.36. [5] LOOMBA R, LIANG TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152(6): 1297-1309. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.009. [6] SMALLS DJ, KIGER RE, NORRIS LB, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation: risk factors and current management strategies[J]. Pharmacotherapy, 2019, 39(12): 1190-1203. DOI: 10.1002/phar.2340. [7] CHEN CY, TIEN FM, CHENG A, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation among 1962 patients with hematological malignancy in Taiwan[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2018, 18(1): 6. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-017-0735-1. [8] AKIYAMA S, COTTER TG, SAKURABA A. Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with autoimmune diseases undergoing non-tumor necrosis factor-targeted biologics[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2021, 27(19): 2312-2324. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i19.2312. [9] SAITTA C, POLLICINO T, RAIMONDO G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: An update[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(7): 1504. DOI: 10.3390/v14071504. [10] ASAI A, HIRAI S, YOKOHAMA K, et al. Effect of an electronic alert system on hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients receiving immunosuppressive drug therapy[J]. J Clin Med, 2022, 11(9): 2446. DOI: 10.3390/jcm11092446. [11] KUSUMOTO S, ARCAINI L, HONG X, et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with B-cell lymphomas receiving obinutuzumab or rituximab immunochemotherapy[J]. Blood, 2019, 133(2): 137-146. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-848044. [12] VOICAN CS, MIR O, LOULERGUE P, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with solid tumors receiving systemic anticancer treatment[J]. Ann Oncol, 2016, 27(12): 2172-2184. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdw414. [13] LAU G, YU ML, WONG G, et al. APASL clinical practice guideline on hepatitis B reactivation related to the use of immunosuppressive therapy[J]. Hepatol Int, 2021, 15(5): 1031-1048. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-021-10239-x. [14] ANASTASOPOULOU A, ZIOGAS DC, SAMARKOS M, et al. Reactivation of tuberculosis in cancer patients following administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors: current evidence and clinical practice recommendations[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2019, 7(1): 239. DOI: 10.1186/s40425-019-0717-7. [15] LIN G, ZHUANG W, CHEN XH, et al. Increase of programmed death ligand 1 in non-small-cell lung cancers with chronic hepatitis B[J]. Ann Oncol, 2018, 29(2): 516-517. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdx694. [16] ZHANG X, ZHOU Y, CHEN C, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients with positive hepatitis B surface antigen undergoing PD-1 inhibition[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2019, 7(1): 322. DOI: 10.1186/s40425-019-0808-5. [17] SCHÖNRICH G, RAFTERY MJ. The PD-1/PD-L1 axis and virus infections: a delicate balance[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2019, 9: 207. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00207. [18] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2017, 67(2): 370-398. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [19] MORENO-CUBERO E, LARRUBIA JR. Specific CD8(+) T cell response immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and viral hepatitis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(28): 6469-6483. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6469. [20] LI B, YAN C, ZHU J, et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade immunotherapy employed in treating hepatitis B virus infection-related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a literature review[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 1037. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01037. [21] WANG X, HE Q, SHEN H, et al. Genetic and phenotypic difference in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion between chronic hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Med Genet, 2019, 56(1): 18-21. DOI: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105267. [22] KUMAGAI S, TOGASHI Y, KAMADA T, et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies[J]. Nat Immunol, 2020, 21(11): 1346-1358. DOI: 10.1038/s41590-020-0769-3. [23] KNOLLE PA, THIMME R. Hepatic immune regulation and its involvement in viral hepatitis infection[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(5): 1193-1207. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.036. [24] EL-KHOUEIRY AB, SANGRO B, YAU T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10088): 2492-2502. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [25] ZHU AX, FINN RS, EDELINE J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2018, 19(7): 940-952. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6. [26] PU D, YIN L, ZHOU Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with HBV/HCV infection and advanced-stage cancer: A systematic review[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2020, 99(5): e19013. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019013. [27] TERRAULT NA, LOK A, MCMAHON BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(4): 1560-1599. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29800. [28] ZIOGAS DC, KOSTANTINOU F, CHOLONGITAS E, et al. Reconsidering the management of patients with cancer with viral hepatitis in the era of immunotherapy[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2020, 8(2). DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000943. [29] TIO M, RAI R, EZEOKE OM, et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in patients with solid organ transplant, HIV or hepatitis B/C infection[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2018, 104: 137-144. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.017. [30] KOTHAPALLI A, KHATTAK MA. Safety and efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy for metastatic melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with viral hepatitis: a case series[J]. Melanoma Res, 2018, 28(2): 155-158. DOI: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000434. [31] SHAH NJ, AL-SHBOOL G, BLACKBURN M, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer patients with HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C viral infection[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2019, 7(1): 353. DOI: 10.1186/s40425-019-0771-1. [32] SCHEINER B, KIRSTEIN MM, HUCKE F, et al. Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)-targeted immunotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: efficacy and safety data from an international multicentre real-world cohort[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2019, 49(10): 1323-1333. DOI: 10.1111/apt.15245. [33] PERTEJO-FERNANDEZ A, RICCIUTI B, HAMMOND SP, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection[J]. Lung Cancer, 2020, 145: 181-185. DOI: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.02.013. [34] LEE PC, CHAO Y, CHEN MH, et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2020, 8(2): e001072. DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001072. [35] ZHANG X, TIAN D, CHEN Y, et al. Association of hepatitis B virus infection status with outcomes of non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy[J]. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2021, 10(7): 3191-3202. DOI: 10.21037/tlcr-21-455. [36] HE MK, PENG C, ZHAO Y, et al. Comparison of HBV reactivation between patients with high HBV-DNA and low HBV-DNA loads undergoing PD-1 inhibitor and concurrent antiviral prophylaxis[J]. Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2021, 70(11): 3207-3216. DOI: 10.1007/s00262-021-02911-w. [37] WONG GL, WONG VW, HUI VW, et al. Hepatitis flare during immunotherapy in patients with current or past hepatitis B virus infection[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2021, 116(6): 1274-1283. DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001142. [38] ZHONG L, ZHONG P, LIU H, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection does not affect the clinical outcome of anti-programmed death receptor-1 therapy in advanced solid malignancies: Real-world evidence from a retrospective study using propensity score matching[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2021, 100(49): e28113. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028113. [39] YOO S, LEE D, SHIM JH, et al. Risk of hepatitis b virus reactivation in patients treated with immunotherapy for anti-cancer treatment[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 20(4): 898-907. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.019. [40] PAN S, YU Y, WANG S, et al. Correlation of HBV DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen levels with tumor response, liver function and immunological indicators in liver cancer patients with HBV infection undergoing PD-1 inhibition combinational therapy[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 892618. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.892618. [41] HAGIWARA S, NISHIDA N, IDA H, et al. Clinical implication of immune checkpoint inhibitor on the chronic hepatitis B virus infection[J]. Hepatol Res, 2022, 52(9): 754-761. DOI: 10.1111/hepr.13798. 期刊类型引用(1)

1. 杜淑兰,石平,张再军. 替雷利珠单抗联合紫杉醇加铂类一线治疗肺鳞癌的效果. 中外医学研究. 2023(24): 15-19 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(0)

-

免疫检查点抑制剂抗肿瘤治疗与HBV再激活的关系-陈顺-附录A.pdf

免疫检查点抑制剂抗肿瘤治疗与HBV再激活的关系-陈顺-附录A.pdf

-

PDF下载 ( 2118 KB)

PDF下载 ( 2118 KB)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术