| [1] |

|

| [2] |

COLLINO A, TERMANINI A, NICOLI P, et al. Sustained activation of detoxification pathways promotes liver carcinogenesis in response to chronic bile acid-mediated damage[J]. PLoS Genet, 2018, 14( 5): e1007380. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007380. |

| [3] |

ROBINSON MW, HARMON C, O’FARRELLY C. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis[J]. Cell Mol Immunol, 2016, 13( 3): 267- 276. DOI: 10.1038/cmi.2016.3. |

| [4] |

LI WP, LI L, HUI LJ. Cell plasticity in liver regeneration[J]. Trends Cell Biol, 2020, 30( 4): 329- 338. DOI: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.01.007. |

| [5] |

LI C, ZHANG ZT, DONG SS, et al. Applications of liver organoids[J]. Sci Sin Vitae, 2023, 53( 2): 175- 184.

李春, 章正涛, 董双舒, 等. 肝脏类器官的应用[J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2023, 53( 2): 175- 184.

|

| [6] |

NESHAT SY, QUIROZ VM, WANG YJ, et al. Liver disease: Induction, progression, immunological mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22( 13): 6777. DOI: 10.3390/ijms22136777. |

| [7] |

WANG FS, FAN JG, ZHANG Z, et al. The global burden of liver disease: The major impact of China[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 60( 6): 2099- 2108. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27406. |

| [8] |

DUVAL K, GROVER H, HAN LH, et al. Modeling physiological events in 2D vs. 3D cell culture[J]. Physiology, 2017, 32( 4): 266- 277. DOI: 10.1152/physiol.00036.2016. |

| [9] |

BAXTER M, WITHEY S, HARRISON S, et al. Phenotypic and functional analyses show stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells better mimic fetal rather than adult hepatocytes[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 62( 3): 581- 589. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.016. |

| [10] |

MARIOTTI V, STRAZZABOSCO M, FABRIS L, et al. Animal models of biliary injury and altered bile acid metabolism[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2018, 1864( 4 Pt B): 1254- 1261. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.027. |

| [11] |

CAMP JG, SEKINE K, GERBER T, et al. Multilineage communication regulates human liver bud development from pluripotency[J]. Nature, 2017, 546( 7659): 533- 538. DOI: 10.1038/nature22796. |

| [12] |

AZIMIAN ZAVAREH V, RAFIEE L, SHEIKHOLESLAM M, et al. Three-dimensional in vitro models: A promising tool to scale-up breast cancer research[J]. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2022, 8( 11): 4648- 4672. DOI: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00277. |

| [13] |

TAGHDOUINI A EL, SØRENSEN AL, REINER AH, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression patterns in purified, uncultured human liver cells and activated hepatic stellate cells[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6( 29): 26729- 26745. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.4925. |

| [14] |

SHINOZAWA T, KIMURA M, CAI YQ, et al. High-fidelity drug-induced liver injury screen using human pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids[J]. Gastroenterology, 2021, 160( 3): 831- 846. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.002. |

| [15] |

NERO C, VIZZIELLI G, LORUSSO D, et al. Patient-derived organoids and high grade serous ovarian cancer: From disease modeling to personalized medicine[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 40( 1): 116. DOI: 10.1186/s13046-021-01917-7. |

| [16] |

LANCASTER MA, KNOBLICH JA. Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies[J]. Science, 2014, 345( 6194): 1247125. DOI: 10.1126/science.1247125. |

| [17] |

HUCH M, GEHART H, VAN BOXTEL R, et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver[J]. Cell, 2015, 160( 1-2): 299- 312. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. |

| [18] |

AKBARI S, SEVINÇ GG, ERSOY N, et al. Robust, long-term culture of endoderm-derived hepatic organoids for disease modeling[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2019, 13( 4): 627- 641. DOI: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.08.007. |

| [19] |

HU HL, GEHART H, ARTEGIANI B, et al. Long-term expansion of functional mouse and human hepatocytes as 3D organoids[J]. Cell, 2018, 175( 6): 1591- 1606.e19. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.013. |

| [20] |

TAKASATO M, ER PX, CHIU HS, et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis[J]. Nature, 2015, 526( 7574): 564- 568. DOI: 10.1038/nature15695. |

| [21] |

SCHUTGENS F, ROOKMAAKER MB, MARGARITIS T, et al. Tubuloids derived from human adult kidney and urine for personalized disease modeling[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2019, 37( 3): 303- 313. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-019-0048-8. |

| [22] |

CHUA CW, SHIBATA M, LEI M, et al. Single luminal epithelial progenitors can generate prostate organoids in culture[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2014, 16( 10): 951- 961, 1- 4. DOI: 10.1038/ncb3047. |

| [23] |

SACHS N, PAPASPYROPOULOS A, ZOMER-VAN OMMEN DD, et al. Long-term expanding human airway organoids for disease modeling[J]. EMBO J, 2019, 38( 4): e100300. DOI: 10.15252/embj.2018100300. |

| [24] |

JO J, XIAO YX, SUN AX, et al. Midbrain-like organoids from human pluripotent stem cells contain functional dopaminergic and neuromelanin-producing neurons[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2016, 19( 2): 248- 257. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. |

| [25] |

BROUTIER L, MASTROGIOVANNI G, VERSTEGEN MM, et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening[J]. Nat Med, 2017, 23( 12): 1424- 1435. DOI: 10.1038/nm.4438. |

| [26] |

ZHANG YJ, HUANG SB, LIU J, et al. Construction and application of innovation gene-edited rats and intestinal 3D organoids models in drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics[J]. Chin J Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 26( 8): 914- 922. DOI: 10.12092/j.issn.1009-2501.2021.08.006. |

| [27] |

WANG YQ, WANG P, QIN JH. Human organoids and organs-on-chips for addressing COVID-19 challenges[J]. Adv Sci, 2022, 9( 10): e2105187. DOI: 10.1002/advs.202105187. |

| [28] |

GAO D, VELA I, SBONER A, et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer[J]. Cell, 2014, 159( 1): 176- 187. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.016. |

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

MICHALOPOULOS GK, BOWEN WC, MULÈ K, et al. Histological organization in hepatocyte organoid cultures[J]. Am J Pathol, 2001, 159( 5): 1877- 1887. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63034-9. |

| [31] |

LIN L, LEI M, LIN JM, et al. Advances and applications in liver organoid technology[J]. Sci Sin Vitae, 2023, 53( 2): 185- 195.

林丽, 雷妙, 林佳漫, 等. 肝脏类器官的研究进展及应用[J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2023, 53( 2): 185- 195.

|

| [32] |

HUCH M, DORRELL C, BOJ SF, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5 + liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration[J]. Nature, 2013, 494( 7436): 247- 250. DOI: 10.1038/nature11826. |

| [33] |

OGAWA M, OGAWA S, BEAR CE, et al. Directed differentiation of cholangiocytes from human pluripotent stem cells[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33( 8): 853- 861. DOI: 10.1038/nbt.3294. |

| [34] |

SAMPAZIOTIS F, DE BRITO MC, MADRIGAL P, et al. Cholangiocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for disease modeling and drug validation[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33( 8): 845- 852. DOI: 10.1038/nbt.3275. |

| [35] |

DIANAT N, DUBOIS-POT-SCHNEIDER H, STEICHEN C, et al. Generation of functional cholangiocyte-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells and HepaRG cells[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 60( 2): 700- 714. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27165. |

| [36] |

WU FF, WU D, REN Y, et al. Generation of hepatobiliary organoids from human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70( 6): 1145- 1158. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.028. |

| [37] |

LI YW, WONG IY, GUO M. Reciprocity of cell mechanics with extracellular stimuli: Emerging opportunities for translational medicine[J]. Small, 2022, 18( 36): e2107305. DOI: 10.1002/smll.202107305. |

| [38] |

HERRERA J, HENKE CA, BITTERMAN PB. Extracellular matrix as a driver of progressive fibrosis[J]. J Clin Invest, 2018, 128( 1): 45- 53. DOI: 10.1172/JCI93557. |

| [39] |

FAN QH, ZHENG Y, WANG XC, et al. Dynamically re-organized collagen fiber bundles transmit mechanical signals and induce strongly correlated cell migration and self-organization[J]. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2021, 60( 21): 11858- 11867. DOI: 10.1002/anie.202016084. |

| [40] |

NIA HT, DATTA M, SEANO G, et al. In vivo compression and imaging in mouse brain to measure the effects of solid stress[J]. Nat Protoc, 2020, 15( 8): 2321- 2340. DOI: 10.1038/s41596-020-0328-2. |

| [41] |

PRIYA R, ALLANKI S, GENTILE A, et al. Tension heterogeneity directs form and fate to pattern the myocardial wall[J]. Nature, 2020, 588( 7836): 130- 134. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2946-9. |

| [42] |

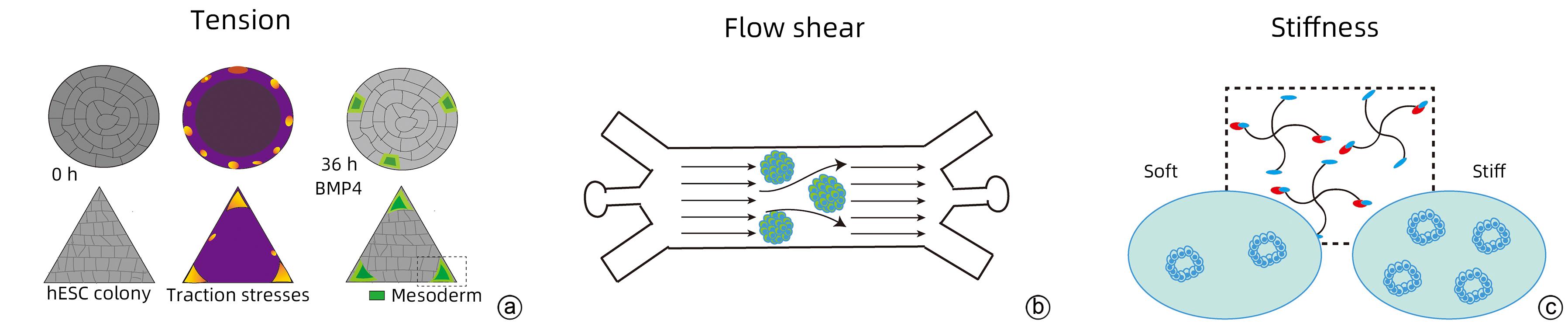

MUNCIE JM, AYAD NME, LAKINS JN, et al. Mechanical tension promotes formation of gastrulation-like nodes and patterns mesoderm specification in human embryonic stem cells[J]. Dev Cell, 2020, 55( 6): 679- 694.e11. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.10.015. |

| [43] |

XUE XF, SUN YB, RESTO-IRIZARRY AM, et al. Mechanics-guided embryonic patterning of neuroectoderm tissue from human pluripotent stem cells[J]. Nat Mater, 2018, 17( 7): 633- 641. DOI: 10.1038/s41563-018-0082-9. |

| [44] |

ABHILASH AS, BAKER BM, TRAPPMANN B, et al. Remodeling of fibrous extracellular matrices by contractile cells: Predictions from discrete fiber network simulations[J]. Biophys J, 2014, 107( 8): 1829- 1840. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.08.029. |

| [45] |

POLING HM, WU D, BROWN N, et al. Mechanically induced development and maturation of human intestinal organoids in vivo[J]. Nat Biomed Eng, 2018, 2( 6): 429- 442. DOI: 10.1038/s41551-018-0243-9. |

| [46] |

LI YW, CHEN MR, HU JL, et al. Volumetric compression induces intracellular crowding to control intestinal organoid growth via Wnt/β-catenin signaling[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2021, 28( 1): 63- 78. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.09.012. |

| [47] |

WANG L, LUO JY, LI BC, et al. Integrin-YAP/TAZ-JNK cascade mediates atheroprotective effect of unidirectional shear flow[J]. Nature, 2016, 540( 7634): 579- 582. DOI: 10.1038/nature20602. |

| [48] |

STEWART MP, HELENIUS J, TOYODA Y, et al. Hydrostatic pressure and the actomyosin cortex drive mitotic cell rounding[J]. Nature, 2011, 469( 7329): 226- 230. DOI: 10.1038/nature09642. |

| [49] |

CAI DF, FELICIANO D, DONG P, et al. Phase separation of YAP reorganizes genome topology for long-term YAP target gene expression[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2019, 21( 12): 1578- 1589. DOI: 10.1038/s41556-019-0433-z. |

| [50] |

DABAGH M, JALALI P, BUTLER PJ, et al. Mechanotransmission in endothelial cells subjected to oscillatory and multi-directional shear flow[J]. J R Soc Interface, 2017, 14( 130): 20170185. DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0185. |

| [51] |

DASH A, SIMMERS MB, DEERING TG, et al. Hemodynamic flow improves rat hepatocyte morphology, function, and metabolic activity in vitro[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2013, 304( 11): C1053- C1063. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00331.2012. |

| [52] |

WANG YQ, WANG H, DENG PW, et al. In situ differentiation and generation of functional liver organoids from human iPSCs in a 3D perfusable chip system[J]. Lab Chip, 2018, 18( 23): 3606- 3616. DOI: 10.1039/c8lc00869h. |

| [53] |

ZHENG Y, XUE XF, SHAO Y, et al. Controlled modelling of human epiblast and amnion development using stem cells[J]. Nature, 2019, 573( 7774): 421- 425. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1535-2. |

| [54] |

HOMAN KA, GUPTA N, KROLL KT, et al. Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro[J]. Nat Methods, 2019, 16( 3): 255- 262. DOI: 10.1038/s41592-019-0325-y. |

| [55] |

KANG YBA, SODUNKE TR, LAMONTAGNE J, et al. Liver sinusoid on a chip: Long-term layered co-culture of primary rat hepatocytes and endothelial cells in microfluidic platforms[J]. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2015, 112( 12): 2571- 2582. DOI: 10.1002/bit.25659. |

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

JUNG DJ, BYEON JH, JEONG GS. Flow enhances phenotypic and maturation of adult rat liver organoids[J]. Biofabrication, 2020, 12( 4): 045035. DOI: 10.1088/1758-5090/abb538. |

| [58] |

MICHIELIN F, GIOBBE GG, LUNI C, et al. The microfluidic environment reveals a hidden role of self-organizing extracellular matrix in hepatic commitment and organoid formation of hiPSCs[J]. Cell Rep, 2020, 33( 9): 108453. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108453. |

| [59] |

KRATOCHVIL MJ, SEYMOUR AJ, LI TL, et al. Engineered materials for organoid systems[J]. Nat Rev Mater, 2019, 4( 9): 606- 622. DOI: 10.1038/s41578-019-0129-9. |

| [60] |

KANNINEN LK, HARJUMÄKI R, PELTONIEMI P, et al. Laminin-511 and laminin-521-based matrices for efficient hepatic specification of human pluripotent stem cells[J]. Biomaterials, 2016, 103: 86- 100. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.054. |

| [61] |

GJOREVSKI N, SACHS N, MANFRIN A, et al. Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture[J]. Nature, 2016, 539( 7630): 560- 564. DOI: 10.1038/nature20168. |

| [62] |

NG S, TAN WJ, PEK MMX, et al. Mechanically and chemically defined hydrogel matrices for patient-derived colorectal tumor organoid culture[J]. Biomaterials, 2019, 219: 119400. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119400. |

| [63] |

ZHANG Y, TANG CL, SPAN PN, et al. Polyisocyanide hydrogels as a tunable platform for mammary gland organoid formation[J]. Adv Sci, 2020, 7( 18): 2001797. DOI: 10.1002/advs.202001797. |

| [64] |

LANGHANS SA. Three-dimensional in vitro cell culture models in drug discovery and drug repositioning[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2018, 9: 6. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00006. |

| [65] |

LIU ZX, FU JX, YUAN HB, et al. Polyisocyanide hydrogels with tunable nonlinear elasticity mediate liver carcinoma cell functional response[J]. Acta Biomater, 2022, 148: 152- 162. DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.06.022. |

| [66] |

SORRENTINO G, REZAKHANI S, YILDIZ E, et al. Mechano-modulatory synthetic niches for liver organoid derivation[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11( 1): 3416. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-17161-0. |

| [67] |

LIU-CHITTENDEN Y, HUANG B, SHIM JS, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP[J]. Genes Dev, 2012, 26( 12): 1300- 1305. DOI: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. |

| [68] |

KECHAGIA JZ, IVASKA J, ROCA-CUSACHS P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2019, 20( 8): 457- 473. DOI: 10.1038/s41580-019-0134-2. |

| [69] |

CHO S, IRIANTO J, DISCHER DE. Mechanosensing by the nucleus: From pathways to scaling relationships[J]. J Cell Biol, 2017, 216( 2): 305- 315. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.201610042. |

| [70] |

CHARRAS G, SAHAI E. Physical influences of the extracellular environment on cell migration[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2014, 15( 12): 813- 824. DOI: 10.1038/nrm3897. |

| [71] |

FLETCHER DA, MULLINS RD. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton[J]. Nature, 2010, 463( 7280): 485- 492. DOI: 10.1038/nature08908. |

| [72] |

HAN YL, RONCERAY P, XU GQ, et al. Cell contraction induces long-ranged stress stiffening in the extracellular matrix[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115( 16): 4075- 4080. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1722619115. |

| [73] |

CHAUDHURI O, GU L, KLUMPERS D, et al. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity[J]. Nat Mater, 2016, 15( 3): 326- 334. DOI: 10.1038/nmat4489. |

| [74] |

RIZWAN M, LING C, GUO CY, et al. Viscoelastic Notch signaling hydrogel induces liver bile duct organoid growth and morphogenesis[J]. Adv Healthc Mater, 2022, 11( 23): e2200880. DOI: 10.1002/adhm.202200880. |

| [75] |

GÜNTHER C, WINNER B, NEURATH MF, et al. Organoids in gastrointestinal diseases: From experimental models to clinical translation[J]. Gut, 2022, 71( 9): 1892- 1908. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326560. |

| [76] |

BEATTY R, MENDEZ KL, SCHREIBER LHJ, et al. Soft robot-mediated autonomous adaptation to fibrotic capsule formation for improved drug delivery[J]. Sci Robot, 2023, 8( 81): eabq4821. DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.abq4821. |

下载:

下载:

DownLoad:

DownLoad: